Home - Teleport Blog - From Zero to Zero Trust - Apr 23, 2020

From Zero to Zero Trust

Blockchain, IOT, Neural Networks, Edge Computing, Zero Trust. I played buzzword bingo at RSA 2020, where the phrase dominated the entire venue. Zero Trust is a conceptual framework for cybersecurity that characterizes the principles required to protect modern organizations with distributed infrastructure, remote workforces, and web connected applications. Zero Trust has gradually emerged over the past two decades as organizations attempted to keep pace with the growing complexity of public and private computing infrastructure.

This article will examine its evolution to contextualize the growing consensus that a network-centric, perimeter-based approach to cybersecurity has become insufficient. We will take a look at early cybersecurity threats in the 1980s, the development of the perimeter security framework, and its shortcomings that birthed Zero Trust in the past decade.

Full Trust

Winding back the clock to the early days of computer networking, we are brought to the prototypical Internet, ARPANET. During these times, cybersecurity was not even a word. The only security measure in place was physical security to protect equipment and computer rooms. After all, ARPANET was a careful selection of researchers, universities, and government agencies; trust was implied. In fact, the first recorded computer virus was a prank. In 1971, Bob Thomas released the Creeper Virus, a harmless program that jumped from computer to computer, displaying the message, “I’m the creeper, catch me if you can!”

It was not until much later that cybersecurity was institutionally recognized. For 15 years, networking technology proliferated and advanced, producing the backbone of the Internet that we use today: TCP/IP, Gateways, IPv4, Ethernet, etc. Then, in 1986, Markus Hess was caught breaking into 400 military computers to sell information to the Soviet KGB, and the US Congress recognized cybercrime by passing the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Coincidentally, the infamous Morris Worm was the first crime to be prosecuted under the Act in 1988, the same year that Digital Equipment Corp published details of the first packet-switching firewall.

Partial Trust

What fundamentally changed in the 1980s was the creation of “Us” vs “Them.” Devices were now connected beyond a core group of trusted institutions and Pandora’s Box had unleashed the Internet to everyone. This point is exemplified well by LANs and WANs. LANs connected a limited area of devices - residences, offices, school - whereas WANs spread over large geographic regions. LANs were insulated private networks distinct from the rest of the Internet. In order to protect privileged information, it became necessary to distinguish between “Us” and “Them.” The solution was a firewall that could filter any traffic originating outside the trusted network, forming a walled enclosure that protected the “Us” from “Them”.

This conceptual perimeter operating model became the standard approach to cybersecurity. However, this framework, also referred to as the castle-and-moat model, was quickly tested. As networking technology and work culture (remote work, mobile phones) evolved, so too did various security measures. Broadly speaking, the challenges facing cybersecurity professionals were:

Extension of the protected network

Packet-switching firewalls existed to protect tightly controlled networks. All traffic could be traced back to a predefined set of networks and devices, demarcating between inside and outside. But this changed as the workforce moved outside the traditional perimeter, opting to work from home, on a business trip, a satellite office, and most importantly, on mobile devices. Security tools, including VPNs, stateful filter firewalls, encrypted communication and authentication methods like passwords and 2FA, all advanced to extend the perimeter, capturing islands of trusted devices in a dangerous sea of unauthorized snoopers.

Incomplete protections within the network

The castle-and-moat model established security defenses against those on the outside with little mention of protections inside. Those who gained access to the network, either through one of the many hastily configured entry points or given credentials, could move laterally within an organization, gaining unauthorized access to sprawling systems. Cybersecurity professionals dealt with this challenge by segmenting networks into component parts with VLANs, routing protocols, internal firewalls, and deployed damage mitigation tools like IDS and SIEM.

Distributed systems communicating over the web

Organizations had tight control over what entered through gateways. But by the 90s, the perimeter had expanded exponentially. Employees had workstations, mobile devices, and personal computers in their homes. Software grew more complex and SaaS emerged. Amazon broke ground with AWS, making software-defined networking the new default. Traditional LANs started to disappear. What was an uninterrupted moat with controlled entry into the castle turned into a disjointed and amorphous blob, pricked full of holes. Solutions emerged in the form of bastion hosts, VPC policies and VPNs, but this only added more bloat to network security.

Zero Trust

Members of the 2004 Jericho Forum concluded that perimeter security was illusory, more akin to a picket fence than a wall. Despite industry efforts, the boundary between private and public networks had been steadily deteriorating in a trend denoted as de-perimeterization. Six years later, John Kindervag coined the term Zero Trust during his tenure as Analyst and VP at Forrester Research.

The basic presupposition of Zero Trust is that a network, private or public, is never secure, period. It fundamentally removes the perimeter, doing away with the paradigm of “Us” vs “Them.” Attention is turned towards directly protecting partitioned resources against explicitly untrusted clients. In other words, a Zero Trust system does not differentiate on where you are, but only cares about who you are.

Doing so does not require a revolutionary approach to security, but instead shifts the focus to:

- Preventing unauthorized access to data and services

- Granular access control enforcement

Exploring further, we can approach a more tangible and practical understanding of Zero Trust.

Implementing Zero Trust

In theory, the argument for Zero Trust is sound, but completely abandoning the entire concept of trusted networks disarms much of the arsenal used to combat cyberthreats. Instead, we must rethink how security is determined.

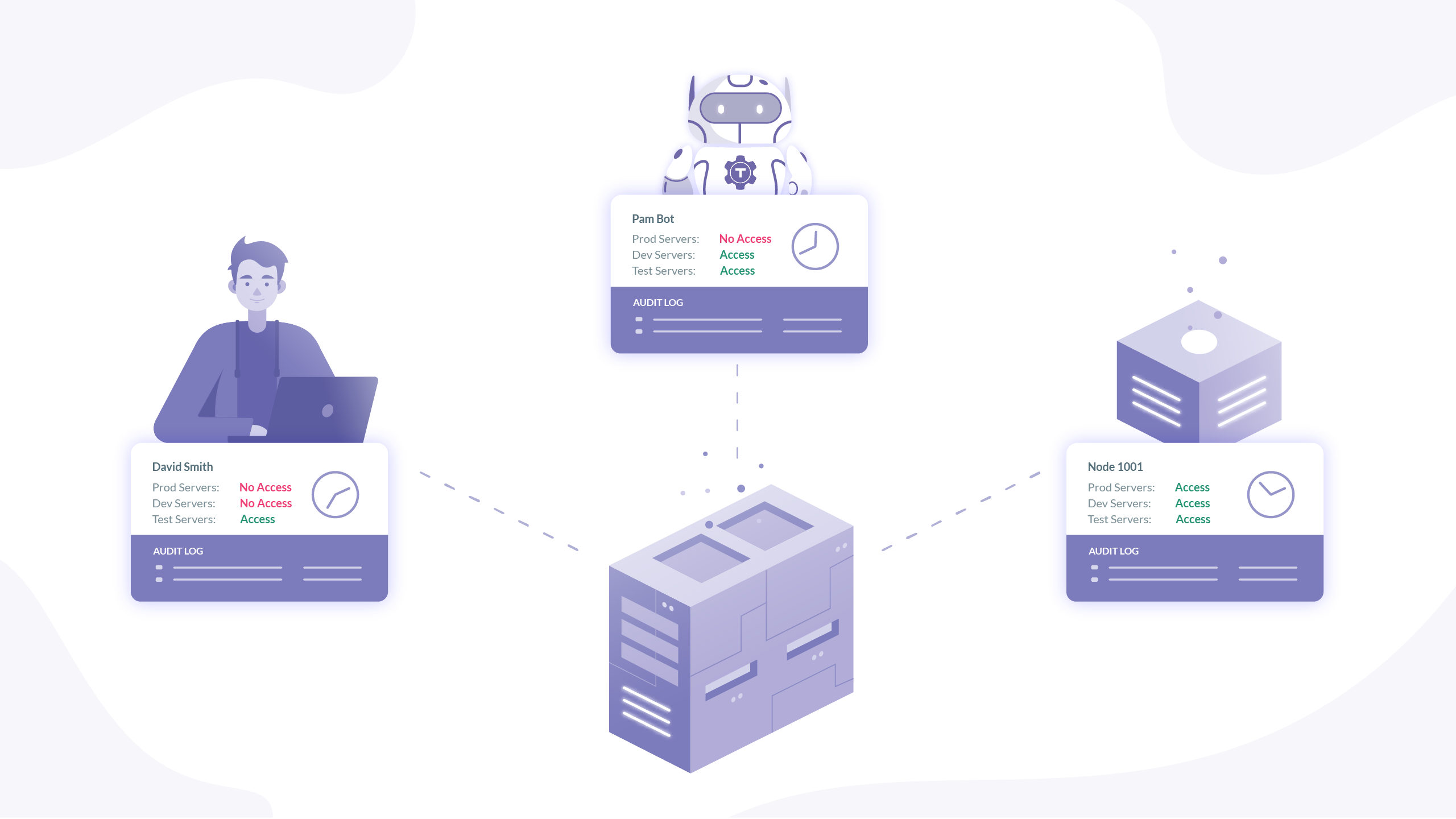

Zero Trust = Authentication + Authorization + Encryption

Recall that no user or machine (microservice) is inherently trusted. By doing away with the concept of external and internal networks, all resources are effectively exposed to corruption and must be treated as such. The solution lies in these three principles:

- Authenticate both users and machines.

- Authorize continuously in accordance with the Principle of Least Privilege

- Encrypt all network traffic, regardless of origin

The preferred method here is to use context aware identity governance, such as IAM or PAM solutions. By implementing a centralized system, responsible for identity and access management across all applications, organizations have a robust way to authenticate and authorize clients instead of relying on proxy information that can be stolen or spoofed, like passwords, SSH keys, and IP addresses. Simply having a password should not be enough to access even your own computer. Users and machines are routinely authenticated from a rich information profile pulled from an identity source, which is fed into a dynamic access policy that authorizes access using the data gathered upon authentication. This is where zero-trust identity management flourishes; having a reliable way to prescribe role based access controls severely limits the damage a malicious or negligent client can do. The final variable in this equation is encrypted communication. Be it user to service, service to user, service to service, or user to user, all communication, machine or human, must be encrypted and protected from end to end. Assuming resources are protected, network traffic still is not. There cannot be an assumption of trusted communication between any parties, regardless of where it originated.

Rethinking Connectivity

Perimeter security applies many of its defenses at the border, leaving few protections internally. This allows for bad actors to move laterally within an organization, entering through an insecure endpoint and navigating to critical infrastructure. The instigators of Target’s 2014 hack achieved their goal in this manner, obtaining credit and debit card information for 40 million customer accounts. Stealing credentials from a contracted HVAC company, hackers entered a trivial application and traversed interconnected networks until they reached payments.

In order to protect against this threat model, organizations must chalk out granular segments around the component parts of a network. This is a three step process:

- All critical data stores, applications, assets, and services must be catalogued. This can range from SaaS providers, to web-connected devices, customer information stores, identity providers, or any other resource that contributes to infrastructure or operations.

- Once catalogued, network traffic must be mapped. This will reveal the interdependencies between each and every resource, laying the groundwork for the next step.

- Having defined the attack surface by its component parts and mapping communication between them, organizations can now construct individual microperimeters. By isolating workloads that are not inherently linked together and creating rigid boundaries, lateral movement beyond the immediate endpoint is restricted.

The word microperimeter seems in conflict with Zero Trust. The very word supports the concept of network-based perimeter security. And in fact, microsegmentation is not Zero Trust. But in reality, not all organizations can switch to an entirely Zero Trust model. Some legacy applications will exist in production in perpetuity and may need to remain protected with network security, albeit with precise granularity. Thus microsegmentation is often seen as a supplemental tool in the Zero Trust model, but by no means a sufficient replacement.

Observability and Audit:

No security system is complete with appropriate analytics. Event logs, user behavior, data exfiltration, etc. are all key components in maintaining visibility over systems and acting in real time. As Zero-Trust is an iterative process, advanced analytics will provide valuable insight into how to improve security posture.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

BeyondCorp

Perhaps the most well-known implementation of Zero Trust is Google’s BeyondCorp initiative, released in 2014. As per Zero Trust doctrine, Google’s goal was to allow employees to work effectively on any network without the use of VPNs, regardless of how secure a network might be. While ambitious in scope, Google successfully moved to a security model that directly authenticated and authorized users and devices instead of relying on network rules.

They then turned this initiative outwards, enabling context-aware access for GCP. Leveraging Google Groups and application level identification, a centrally managed identity and access management system is able to unify access control for Google Cloud services. Filtering requests through a web-accessible API, identity aware proxy services use identity and context information to determine degrees of authorization. For added protection, administrators can define security perimeters around GCP resources, down to each microservice if needed, controlling communication and securely sharing data. BeyondCorp’s exhaustive coverage embodies many of the principles discussed above and is a great practical implementation to study.

As Google has prophesized this approach and shown how it can be successful, other companies have attempted to emulate them. However, most of them do not have the same security and engineering resources. Subsequently, we have seen both a shortage of talent skilled in these new methodologies and a plethora of new Zero Trust vendors and solutions emerging in the developer and security software markets.

Conclusion

Adopting a Zero Trust cybersecurity framework ranges in difficulty. Companies that host their entire infrastructure and applications on cloud providers will have an easier time than companies that have been around for decades and have a varying array of outdated to contemporary technologies. But the fact remains that network perimeter security is no longer the advised best practice. Networks grow in complexity day by day: Labor forces will continue to spread across the globe, infrastructure will continue to fragment across physical and virtual servers, and applications will continue to communicate through public networks. Facing these realities, organizations will need to adapt and modernize, or risk being another headline.

Tags

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter