Teleport Blog - SaaS Design Principles with Kubernetes - Feb 9, 2021

SaaS Design Principles with Kubernetes

It seems like nowadays, every company is a SaaS company. We’ve even begun stratifying by what is sold, replacing the “software” in SaaS to whatever the product’s core competency is, search-as-a-service, chat-as-a-service, video-as-a-service. So, when we, at Teleport, set sail for the cloud after years of successfully navigating on-prem software, we came in with a different set of experiences.

Turns out, porting a tool designed to be self-hosted to something hosted isn’t as simple as pulling our build image from quay.io. Well, in a way it is, but what I mean is that the SaaS route poses a different series of design challenges than on-prem. The product is the same, but not how users interface with it. This post explores how we deployed Teleport Cloud on Kubernetes, deliberately designing for maximizing security, minimizing resource consumption, and self-service.

Teleport Cloud Terminology

To follow along with Teleport-specific concepts and terms, we need to cover the basics.

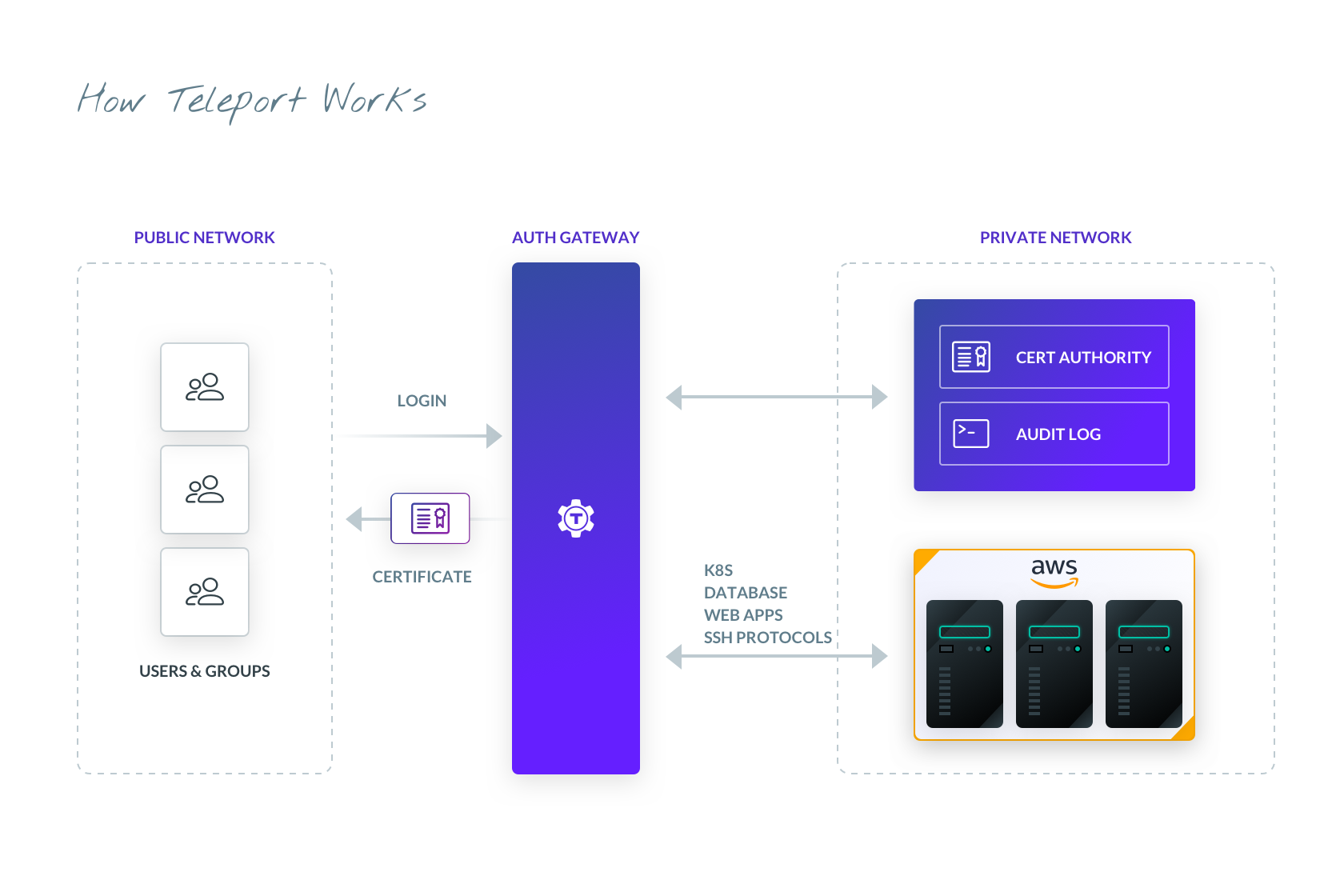

Figure 1: How Teleport Works

At its core, Teleport Access Platform enables engineers to quickly access any computing resource anywhere.

- Teleport terminology includes:

- Resource - Server, database, web app, or Kubernetes cluster

- Client - Users and machines processes attempting to access resources

- Proxy Service - Stands between users and resource

- Auth Service - Responsible for issuing and authenticating certificates

- Node Service - Daemon running on resource(s)

- Client initiates connection to resources through the proxy service, either presenting a short-lived certificate or requesting one from the auth server

- Auth service authenticates the digital signature on the certificate

- Proxy service grants access resources behind it

- Node service queries auth service API to check permissions described in the certificate

- User has obtained role based access to the resource

For all the standard reasons, we deployed Teleport Cloud as a Kubernetes cluster on AWS. Each customer is given their own Kubernetes namespace to isolate resources like pods, deployments and supporting services like load balancers, S3 buckets, and databases. Taken together, each customer has their own tenant within the Kubernetes cluster. Teleport Cloud is currently in a private beta, but is slated for GA on March 1st.

Self-Service

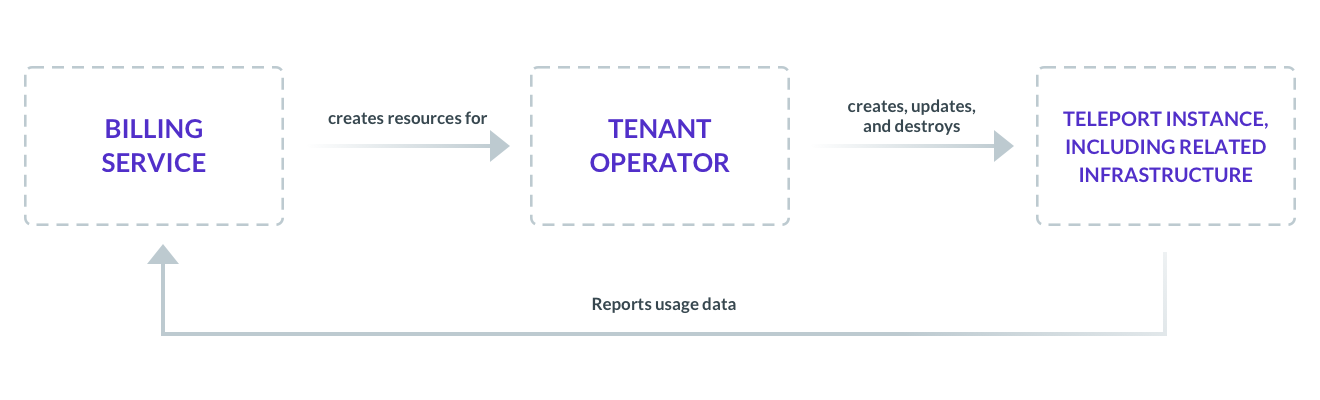

Our core design principle was to make it convenient for developers to use Teleport Cloud. Many of us use Teleport and other software in our home labs. We don’t want to have strings attached to play with new software. To meet this design principle, we had to remove ourselves entirely from the equation, leaving behind a functional closed system. We landed on introducing two new components between Teleport and Teleport Cloud, a single billing-service and single custom Kubernetes operator.

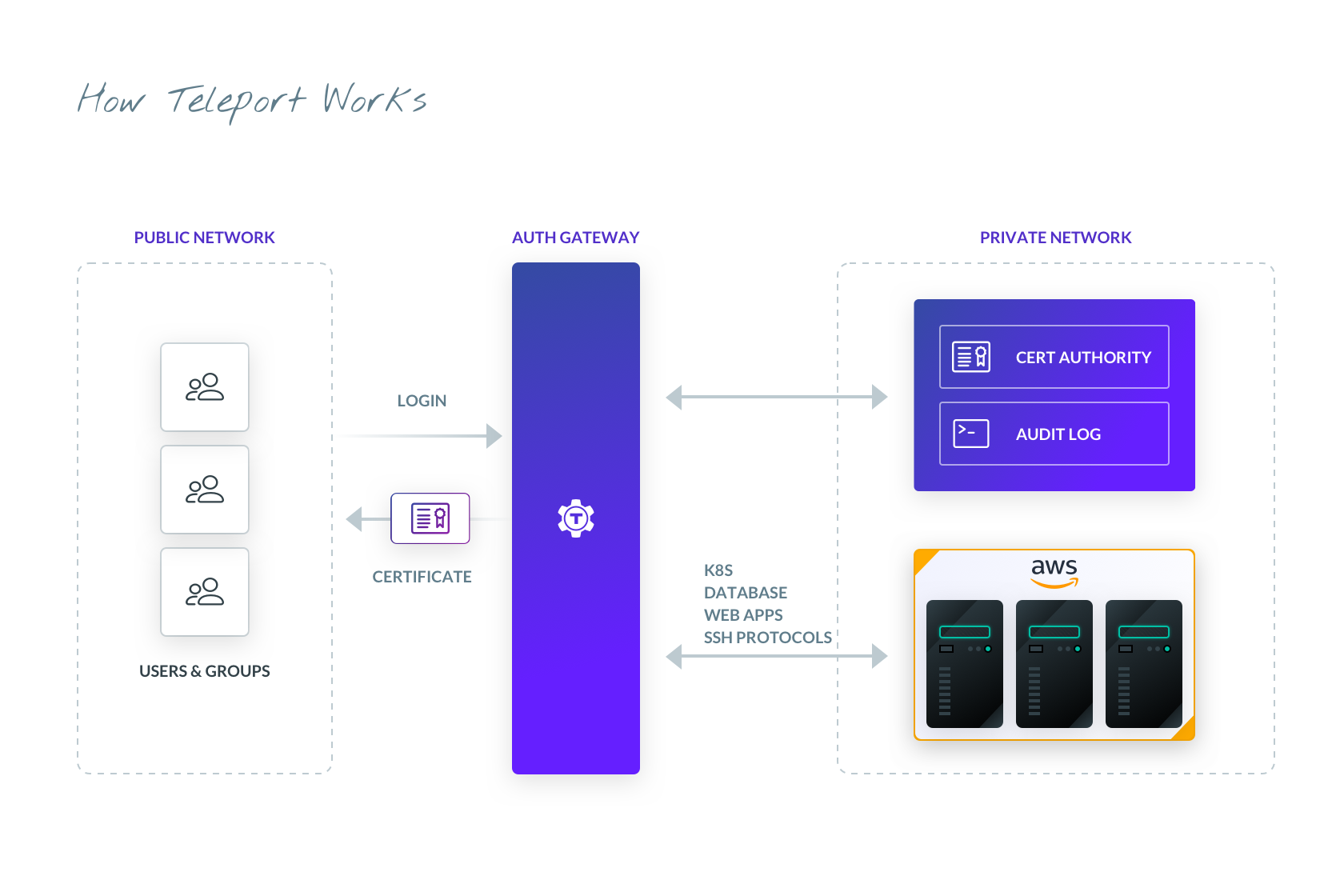

Figure 2: Teleport Deployment

The billing-service is a Go app complete with its own council of microservices and APIs to manage customer account information - think

billing and subscription. When customers fill out the sign-up form and describe their tenants, the information gets propagated to the

billing-service. Using a built in Kubernetes client, the billing-service creates a custom resource kind: Tenant.

The tenant-operator is a custom

controller, built using the

kubebuilder framework. It extends the Kubernetes API to manage stateful operations - in

this case, on AWS. Whenever a new state change is made to a Tenant resource in a cluster (like creating a new tenant), the tenant-operator

responds by provisioning compute infrastructure to match the expected state. The Teleport instance itself communicates to the

billing-service to report usage. Through an API in the billing-service, customers can review their usage and make changes to resource

consumption as necessary, starting the loop all over again.

In the darkest timeline, we would take the place of the billing-service, forcing some contrived interaction. But with the billing-service, customers are mostly able to interact with their deployment without us.

Idle Resource Consumption

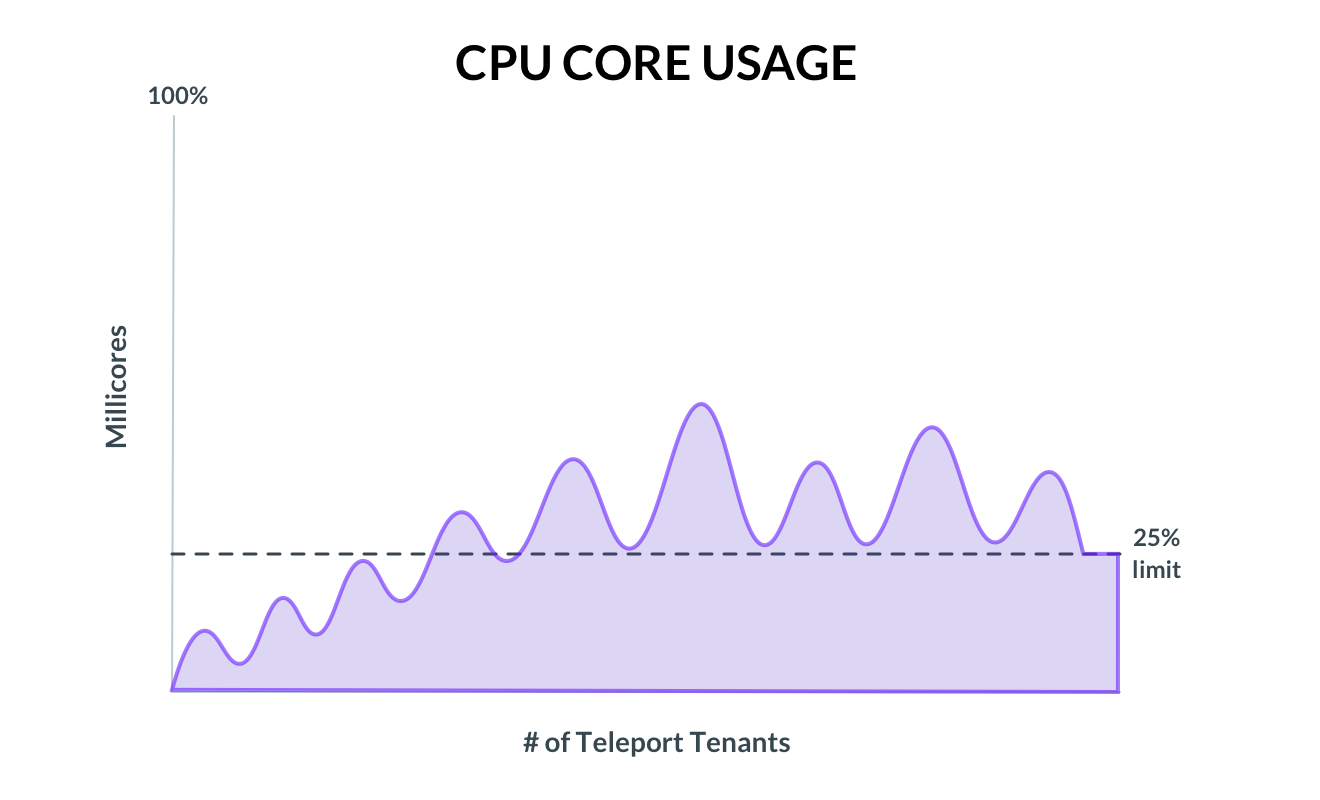

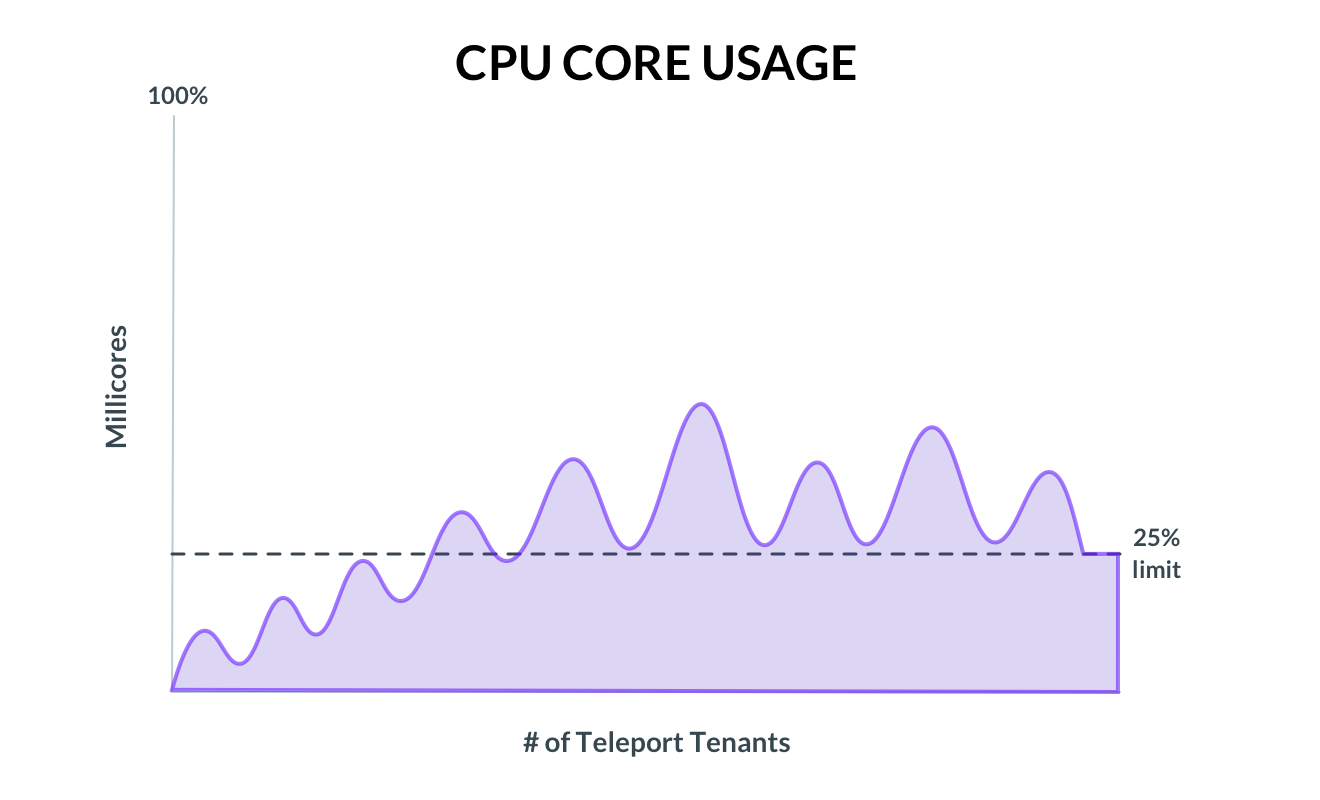

Just like every cloud-hosted offering in existence, Teleport Cloud needed to be lean, balancing a fine line between cost and availability. We had powerful tools at our disposal by deploying on Kubernetes, letting us monitor CPU usage and dynamically scale in real time. Problem is, we needed time to collect and draw conclusions from the data… But what do we do until then?

Figuring out how to allocate processing power was a bit of a guessing game for us. With our on-prem version, we never sent any data from Teleport back to us, obfuscating patterns in user behavior. We only had partial answers to questions like, “What’s the difference between a deployment of 5 Teleport proxies vs. 50 vs. 500?” and “How does usage change when Teleport is used for server access and Kubernetes access?” Having this information would give us some confidence in efficiently provisioning server resources to new sign-ups based on descriptive inputs, like number of users, resource type, region, and a dozen other details.

In time, we would collect this data. Not that it would be difficult. Running Prometheus to monitor our Kubernetes cluster lets us gather system data on containers, pods, and nodes. Once aggregated across resource consumption, requests, and limits, we could answer questions that we were previously in the dark about. Not to mention the basic promise of Kubernetes with horizontal and vertical autoscaling.

But we’re skipping a step here, attempting to run without learning to walk. Right now these metrics mean very little to us; the sample size is too small. Instead, we had to create a default state for creating new tenants. We needed a naive allocation policy. To this end, we had only one data point to work with, the cost of an idle Teleport instance, between the proxy and auth server, is roughly 50 millicores. Packing a core for 20 tenants would max out capacity, assuming no user activity. (This number goes down as more proxy/auth servers are added to a tenant, increasing idle consumption.) To account for activity, we used a 1:4 ratio of dedicated resources to pooled resources to be shared between tenants. In other words, we reserve 75% of CPU for bursts forcing the Kubernetes scheduler to only allocate ¼ of available compute. As new tenants are created, nodes are packed tighter and tighter until idle consumption reaches 25%. At this point, we manually provision a fresh CPU to begin packing, though at some point we’ll introduce an autoscaler to do the part.

Figure 3: Allocated CPU Cores

This ratio of 1:4 is somewhat the result of guesswork. After all, we made this approximation exactly because we haven’t had time to gather data. But as we learn how server resources are actually used by customers, we can tune their configuration and start to shrink that 75% down to something more reasonable.

Authentication and Authorization

It took us five years to join our peers in the cloud because cloud did not provide the security and privacy that necessitated a product like Teleport in the first place. Most of our early customers were uncomfortable letting Teleport call home, let alone exposing their bare-metal production environments to a public endpoint. As we grew, we began to be approached by companies without these limitations, but being a component of critical infrastructure still required strict security standards. Over the years we gained valuable experience going through dozens of vendor security reviews and compliance checks. And with that information, we designed Teleport Cloud to preempt any objections we could expect.

On the surface, we made sure tenants never shared resources or data. Recall each customer has their own Teleport instance and set of supporting services. All tenants are deployed on the same physical cluster, but by attributing individual namespaces to each, customers had their own dedicated virtual cluster.

Digging deeper, we see that the billing-service and tenant-operator have their own scope of responsibilities and permissions. For example,

the tenant-operator has privileged access to databases, load balancers, and S3 buckets while the billing-service provides billing and usage

information through the Teleport web UI. It follows that these components should have their own IAM policy, just like a sysadmin and QA

tester have theirs. Using kiam, we can associate IAM roles to pods. Kiam adds a meta-data description to

pods, which the agent reads as it intercepts requests to the AWS API, rejecting any that do not correspond to their IAM role. The pod below,

belonging to the billing_service IAM role, would be prohibited from requesting database credentials from Amazon’s metadata services,

something that could have saved CapitalOne a lot of

trouble in their 2019 data breach.

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: foo

namespace: acme.corp

annotations:

iam.amazonaws.com/role: billing_service

On the topic of secrets and credentials, another important security design choice was using kubernetes external secrets, which extended the Kubernetes API to access external secret managers, like AWS Secret Manager or Hashicorp Vault. It’s main use case is to manage our support and sales access to customer account data. When spinning up a new database with Terraform, a random password is generated and stored as credentials in AWS Secret Manager. Using the kubernetes external secrets project to fetch credentials, they need not be stored in plaintext in the deployment file, and can be rotated and encrypted within the secret manager.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

Conclusion

Teleporting to the cloud has been a dream of ours for a while, but just wasn’t viable at the time - we open-sourced Teleport back in 2016, just two years after Kubernetes was. In the four years we waited, the Kubernetes ecosystem has exploded in depth and breadth. Only recently have kiam and kubernetes external secrets become production ready. Without the right tools, convincing anyone to pay for a hosted version of Teleport would have been impossible.

If you're interested in trying a fully hosted Teleport, you can sign up here and let us know what you think!

Tags

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter