Home - Teleport Blog - Unify Access to Cloud - Iterating on Identity-Based Management

Unify Access to Cloud - Iterating on Identity-Based Management

The maturation of software development has been driven by the increasing segmentation of functions into their own portable environments. Infrastructure is splintered into dozens of computing resources, physical servers, containers, databases, Kubernetes pods, dashboards, etc. Such compartmentalization has made it incredibly simple for developers to enter their desired environments with minimal disruption to other working parts. To keep this rapid pace of development, sysadmins, SREs, and their counterparts are tasked with supporting dynamic infrastructure capable of responding to the DevOps process, whether this be automation or access.

Tasked with stitching together a fluid network of compute environments, operators often find themselves struggling with the same problem of how to maintain meaningful control of or visibility into activity. Dealing with hundreds of remote engineers accessing thousands of ephemeral instances over different transport protocols produces an overwhelming number of users, secrets, and sessions that all require tracking and logging.

Identity management solutions have helped somewhat. Being able to SSO into apps like Slack or Jenkins adds some much-needed finesse, but are incomplete in coverage. The next iteration will be to use the same identity object to authorize privileged access to servers, clusters, apps, databases, desktops, routers, and every other possible cloud resource. The aim should be to unify access controls across the entire stack, not just the outermost layer: a single place to define, enforce, view, and manage global auth. To understand why the next big step will inevitably head in this direction, we will look at some common pain points, how they’ve been exploited, and how identity-based management can release pressure.

Secret sprawl

When a server is presented with a valid secret, it holds an important assumption that the bearer on the other end of the exchange is not a fraud. Possession is a proxy for identity. We know this is not true - secrets have a nasty habit of getting around. Why? Because it’s convenient.

Internal security teams will preach that the “correct” method is to issue a secret per user, but that would inevitably bury developers under a mound of credentials. It’s faster to just share secrets by hardcoding them into an application or storing them in plaintext in S3 Buckets for ease of use. Amplifying this threat vector, modern infrastructure generates a mountain of secrets daily. Each cloud compute service mints its own set of keys. Agile methodology and supporting DevOps tools means bespoke deployment environments for all teams. And yes, while secret management tools help contain the sheer volume of secrets, some will be leaked, misconfigured, lost, shared, or stolen.

A European supercomputer hijacking earlier this year provided a cautionary tale in sharing secrets. Supercomputers are a utility, providing unparalleled computational power to an ecosystem of users. In this case, these users included institutions working on COVID-19 research. Universities in China, Canada, and Poland had all been issued SSH keys, which were shared between academics within their respective universities. These credentials were then stolen and used in a coordinated attack on multiple supercomputers to mine cryptocurrency.

The problem is abstraction. Secrets are an abstract representation of a user and can switch hands. They are one-dimensional codes that map to a persona, not a person - the “what,” not the “who.” In the supercomputer incident, the persona was a group of academics within a university. And so when hackers presented a valid SSH key, the supercomputer did not - and could not - notice the fraud.

Endpoint propagation

Almost anything can be referred to as a “workspace” nowadays. There is an expectation that employees will need access to computing resources in highly variable circumstances. In 2020, trends like remote work and using personal devices were shoved into normalcy, circumventing many of the defenses that cybersecurity professionals relied on. Combine this with compute infrastructure that has been divided across different computing environments (VMs, Docker, Kubernetes), and it’s plausible for an engineer to want to peek into a running container at midnight from the in-laws a couple states over.

Dependably, we can turn to cryptocurrencies for another case study. Hacking a computing resource to run a crypto-mining rig has become a profitable hobby for some years now. It does not take long to find examples of poor access hygiene in carelessly exposed endpoints. Hosts with exposed Docker APIs we used to create and run containers with mining rigs. One attack accomplished the same feat through an opening to Kubeflow clusters. Tesla’s passwordless Kubernetes console added the company to a growing list of victims of similar circumstances.

Permeable boundaries

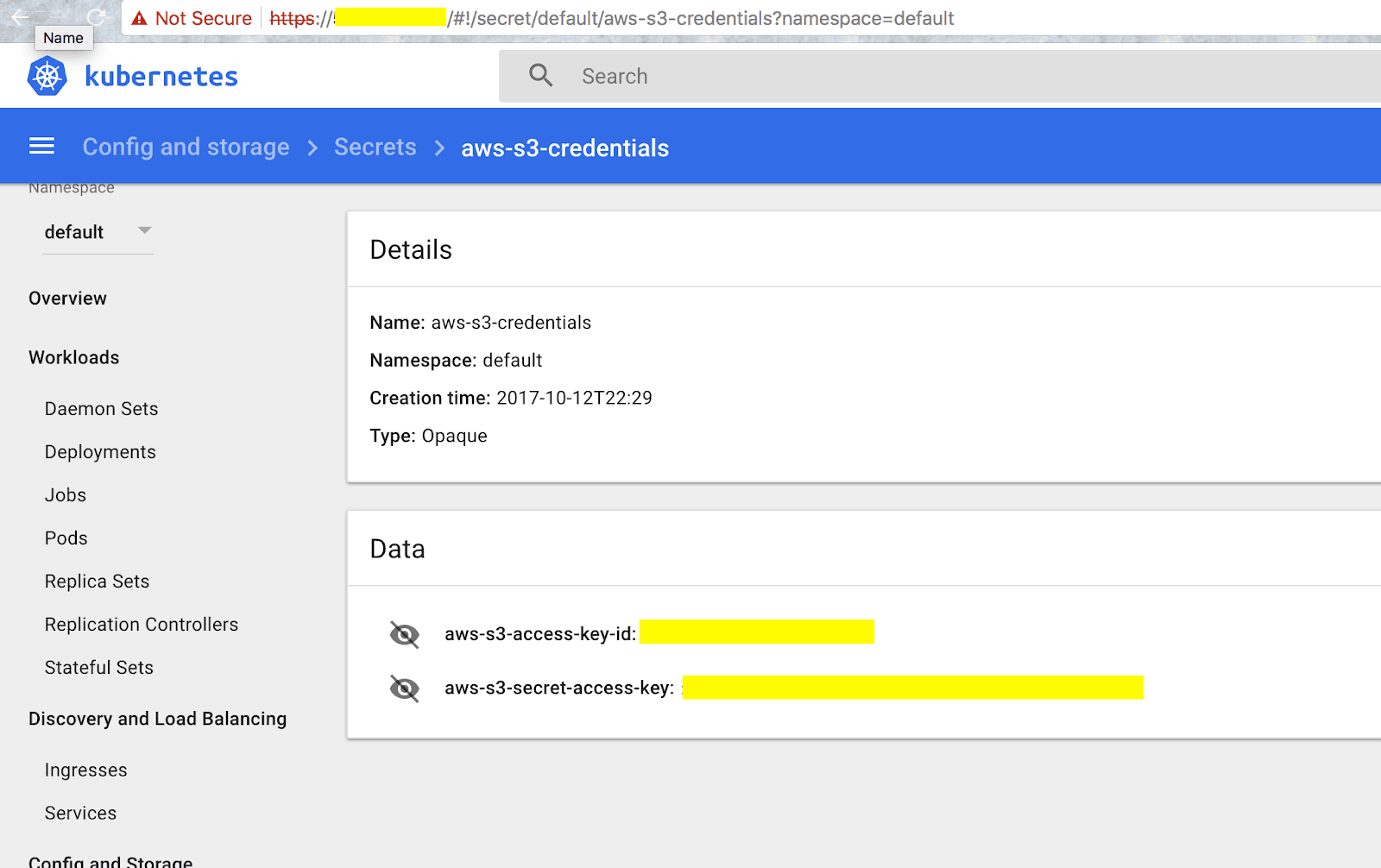

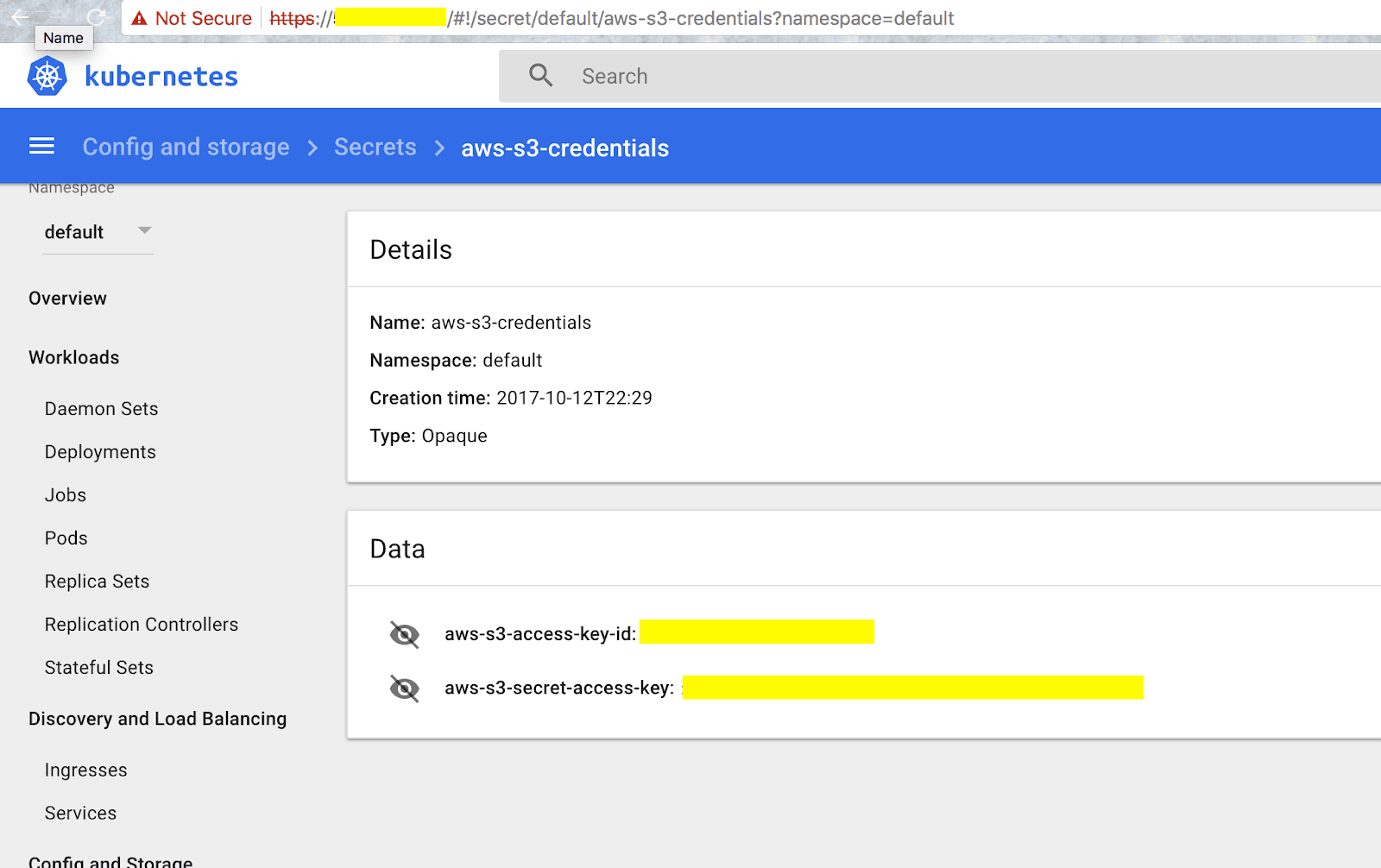

Once attackers had found their way into one of Tesla’s Kubernetes pods, they would come to find a set of credentials to an Amazon S3 bucket hiding in plain sight (Figure 1). Computing resources do not exist in a vacuum. They are intimately networked together. Hopping from one environment to another just requires an open port and a short protocol ride. If someone had infiltrated your network, how easy would it be for an intruder to scan for vulnerable databases, like the Equifax hack? Or how about secrets scattered across internal wikis, like Twitter? How long would it take to move between a third-party vendor’s system into credit card information, like Target?

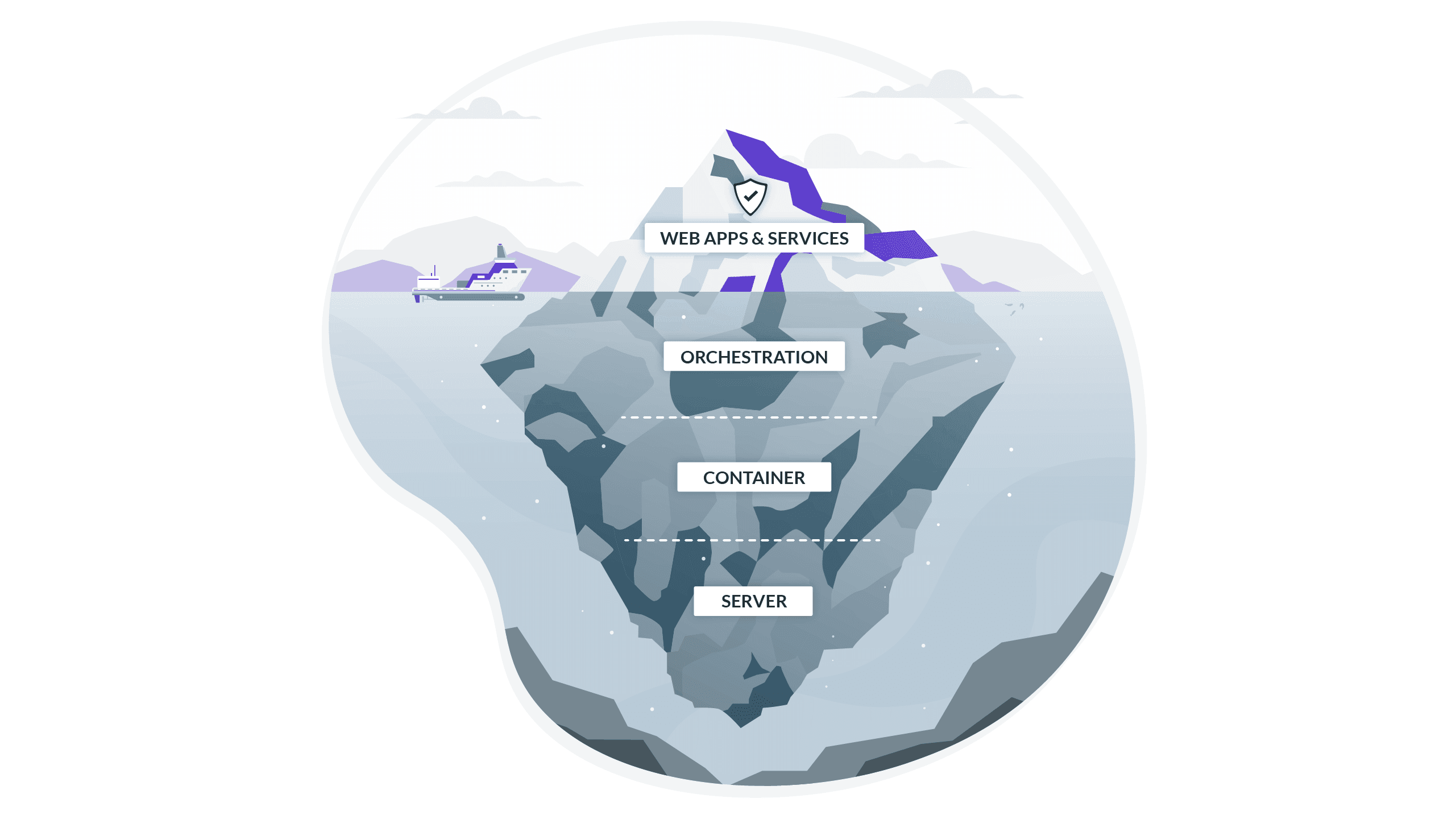

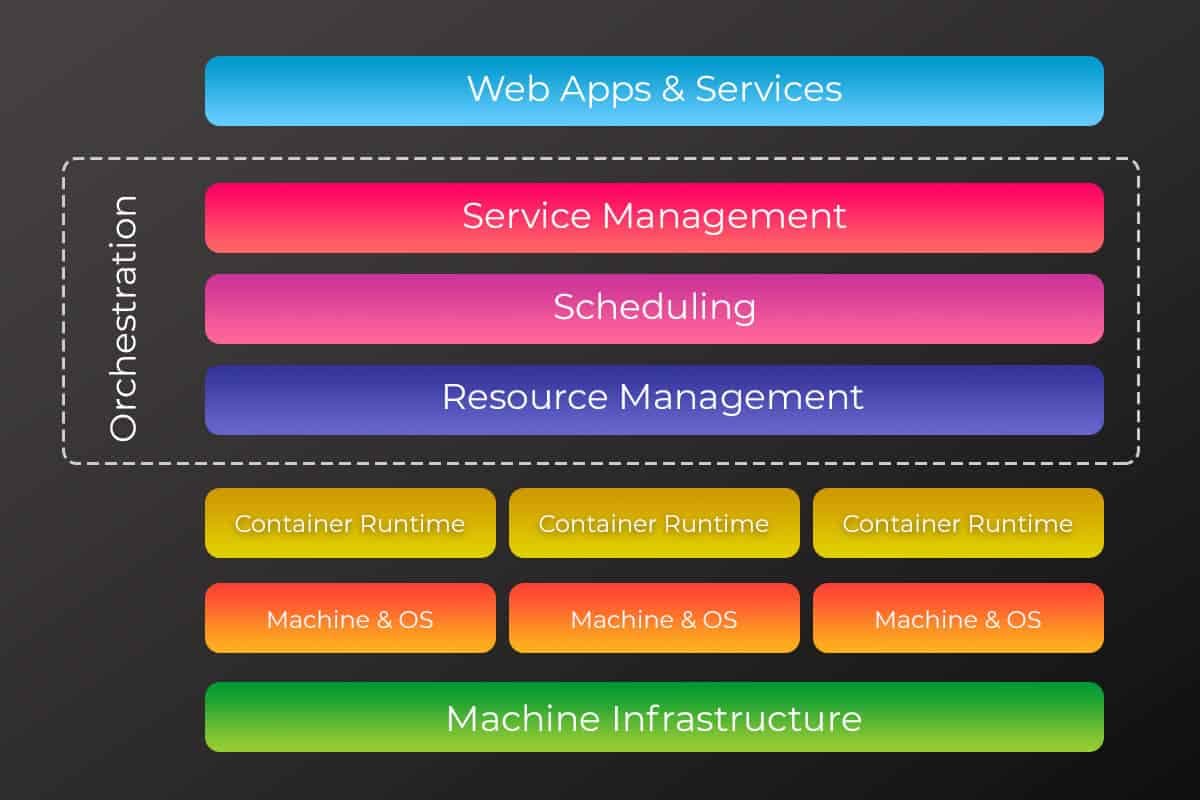

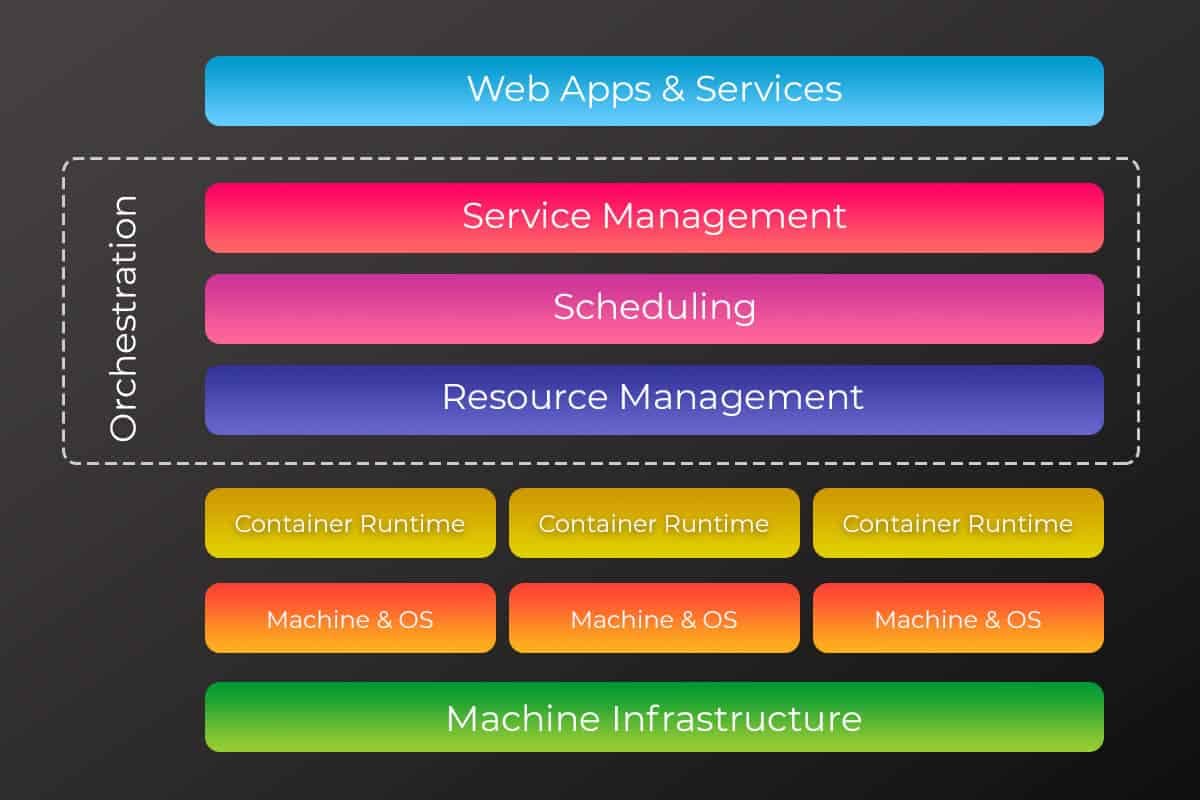

Each layer of abstraction creates its own station for cyberthreats to gather and wait to be ferried elsewhere. Figure 2 stacks these different layers together, showing us where someone can enter from and where they can break out to. Take this post on hacking a Kubernetes cluster, exploiting the same vulnerability used at Equifax. The author, Dieter, hacks a small Kubernetes cluster housing an app container for Apache Struts. Scanning with netcat for an open port, he is able to run a script with the exploit and inject a command that connects a reverse shell! What should he do next? Run a container as root? Deposit an SSH key? Break out of the cluster into the host?

The point is not that everything is compromised all of the time. Rather, even if networks are staunchly guarded, clients and hosts are configured without mistake, and secrets are encrypted, there can still be unforeseeable events that make use of innately permeable boundaries. By constructing IT systems with plug-and-play building blocks, we inadvertently create a giant digital maze with way too many entrances and not enough dead ends.

Cloudy and poor visibility

If you’ve ever skied during a whiteout, you’ve experienced firsthand how terrifying it is to speed down a mountain while snow obscures any meaningful visibility. The only way to avoid obstacles is to get within range, close range. It’s not so different from administering remote access. Instead of dodging trees and cliffs, professionals are looking for abnormal behavior with blinders on. They are unable to answer the questions, “Who ran that query in my database?” “How many of my employees can access customer data? Who is currently in my production environment?”

Earlier, I pointed out that a secret can represent a user, but tells us very little about the user. This gets to the heart of the problem

- access is not granted from identity information about the user, i.e. What is their name? What team are they on? What role do they play? Are they a vendor or a contractor? What’s off limits? Instead, we use representative information of who the user persona might be. Unable to limit access based on “who,” we rely on the “whats,” proxy information like valid keys, IP addresses, or just plain username and passwords. And because users lack unique characteristics, they cannot easily be discerned from the other people and machines going about their business.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

Govern access beyond SaaS with identity

Some companies have gotten ahead of this trend and switched to a model that counsels identity-based access. The method is aptly named. Access does not depend on presenting the right credentials. Instead, a personal profile of the user gets fed through a policy that divines permissions from descriptive data, like those in the previous paragraph. Because of identity providers, like Okta, Active Directory, Keycloak, etc. identity data is centrally housed, making it a reliable information source to help guide decisions.

Identity-based access is mostly limited to the realm of web apps and services. When we think of IDPs, we’re primarily concerned with logins to email or workplace tools for new hires, but that’s just one component of the overall architecture (topmost layer of Figure 2). For the longest time, sysadmins did not have to worry too much about remote access protocols, as engineers were co-located with the services they used. But now, we use a dozen different SaaS tools, which is why SSO is everyone’s best friend. But if your engineering teams are still sharing static SSH keys or database credentials, let alone leaving a public dashboard without a password, the most catastrophic threats still loom.

More concretely, what I mean by consolidating access is a digital command center to manage authentication and authorization between web apps, Kubernetes clusters, databases, and servers all in one place. We do not currently do this, and it’s no surprise that we don’t! There’s no consistency across different remote access protocols. It’s easy to bundle SaaS applications into a universal SSO flow because they all travel over HTTP. But HTTP is a different beast from SSH or LDAP. Logging into email is an entirely different process from using an SSH key. But when Maurice checks his inbox or runs a shell script, he is the same person with the same identifiable character traits. That level of consistency can and should be used for all protocols. In other words, the centralization of identity management around identity providers offers an opportunity to unify access controls around all company resources. Identity-based access does not care what transport layer protocol is being used. The experience is similar to “Log in with Google,” but instead restricts junior devs from entering product servers, as per company security policy.

As long as the world continues to grow more connected, new layers will form. Right now, Kubernetes is the newest kid on the block, but it won’t be long until another emerges and is added to the stack. Instead of rehashing the same problem of secure remote access with secrets and VPNs, switch to a model that unifies access controls and scales with your infrastructure, not against it.

Table Of Contents

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Tags

Subscribe to our newsletter