Home - Teleport Blog - Anatomy of a Cloud Infrastructure Attack via a Pull Request - Sep 16, 2021

Anatomy of a Cloud Infrastructure Attack via a Pull Request

In April 2021, I discovered an attack vector that could allow a malicious Pull Request to a Github repository to gain access to our production environment. Open source companies like us, or anyone else who accepts external contributions, are especially vulnerable to this.

For the eager, the attack works by pivoting from a Kubernetes worker pod to the node itself, and from there exfiltrating credentials from the CI/CD system. Critically, this vulnerability exposed production AWS credentials that could be used to alter release artifacts and access production cloud services.

Once discovered, we immediately fixed our CI system to prevent this attack from occurring. Our response team’s analysis found no evidence this vulnerability was exploited or any data was tampered with. Even so, we encourage customers to upgrade to the recently released Teleport 4.4.11, 5.2.4, 6.2.12, or 7.1.1.

In this post, I will walk through the vulnerability and focus on some key areas where we are improving our CI/CD tools and practices.

Context

Teleport is an open-source company; we maintain public GitHub repositories where the general public can interact with us and contribute code. When a developer — whether internal or external — wants to contribute, they open a Pull Request (PR) and our Continuous Integration (CI) system validates, builds, tests, and runs the contributed code.

By definition, running CI on Pull Requests is remote code execution: A contributor submits code and our CI system runs those contributions on Teleport infrastructure. Automatically executing CI against unapproved PRs from external contributors was our first mistake. From that initial remote code execution, we uncovered several isolation errors allowing a PR to escape its isolation mechanism and pivot to the Drone server and its secrets.

Technical details

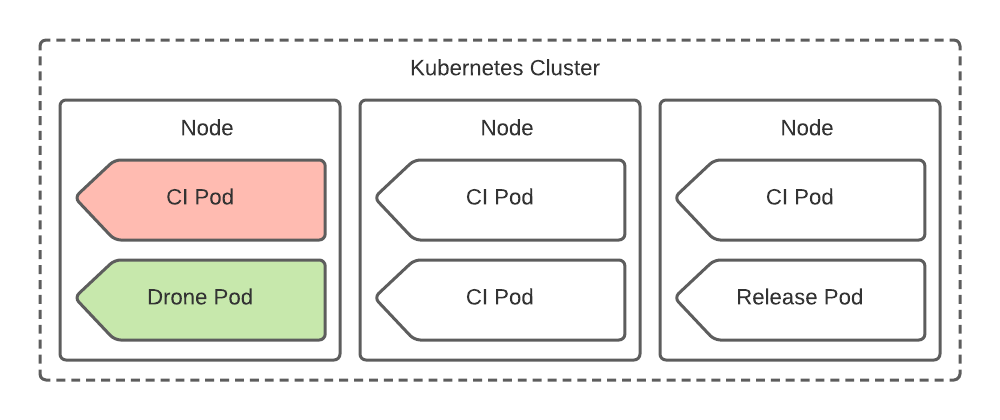

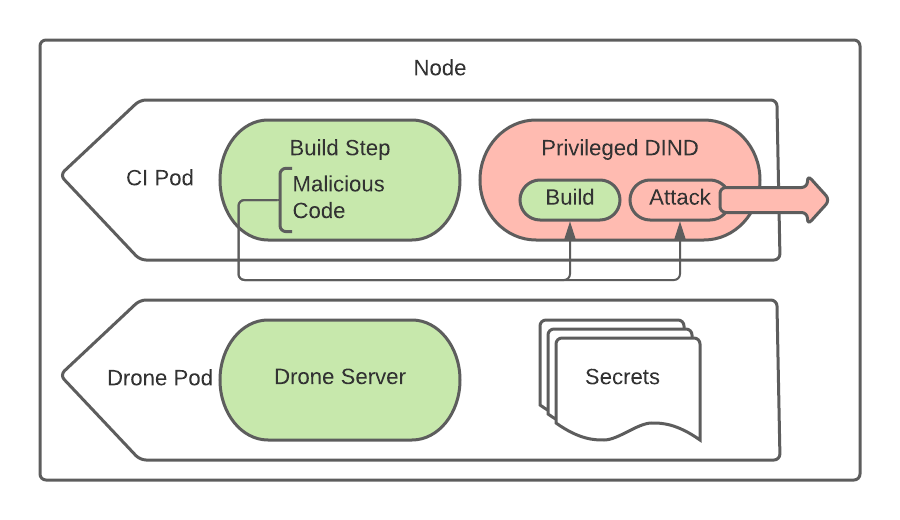

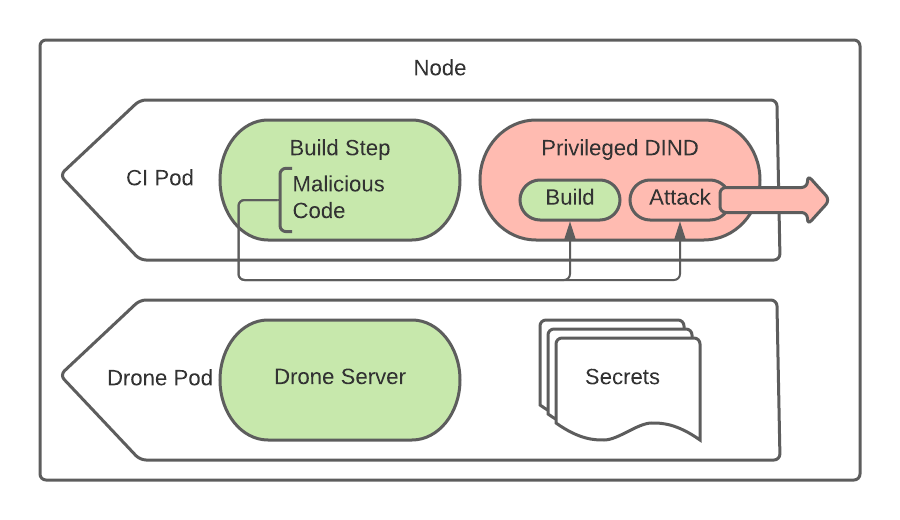

To understand the attack, it is first helpful to understand Teleport’s former CI deployment. We deployed a Drone CI instance and its jobs as pods inside a Kubernetes cluster. Drone Service pods, CI job pods, as well as Release automation pods were configured to run with common scheduling parameters, resulting in a mix of workloads across homogenous nodes.

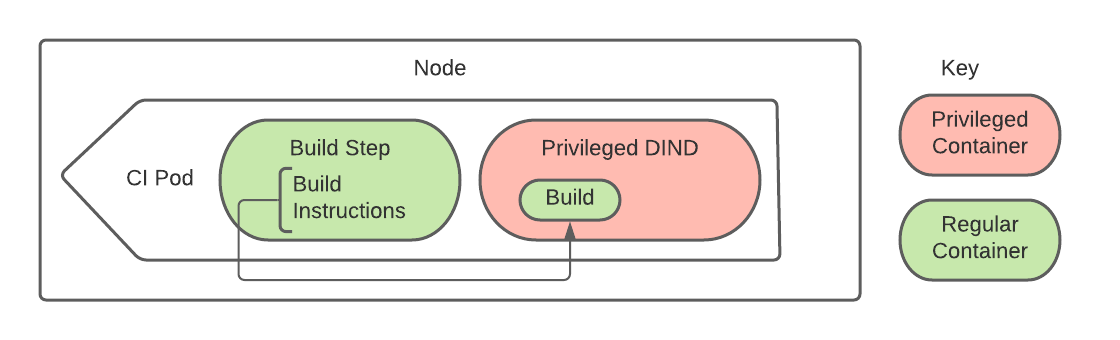

Within the above Kubernetes pods, our CI jobs run code in unprivileged containers. However, much of our automation is dependent on running Docker commands for improved determinism and cross-platform development. For jobs that require Docker, we utilize a privileged docker-in-docker (DIND) sidecar container. Code running within the unprivileged build container can talk to this DIND sidecar, allowing CI to use the same automation that developers run on their workstations.

With this setup, an ill-intentioned Pull Request can request that DIND run a privileged container crafted to escape Docker’s sandbox. Using any number of privileged container escape techniques, a Pull Request job could use this privileged container inside DIND to escalate to root access on the node itself.

After the attack escapes to the root on the node, secrets from other pods on the same host can be harvested by inspecting container environments. While not all pods are “lucky” enough to land on the same node as a Drone Server pod or a Release pod, due to the shared scheduling parameters, it is a waiting game until a pod with valuable secrets is scheduled on a compromised node.

Exfiltrating secrets from the Drone Server pod is a juicy target to begin with. However, because our Drone instance served internal and external CI/CD workflows across the company, the secrets it held could pivot to a wide array of critical infrastructure: release artifacts for Teleport and Gravity, Teleport Cloud backend services, legacy billing infrastructure, private GitHub repositories and the web servers backing this blog post.

Response

We used this internally discovered vulnerability as an opportunity to practice our security incident response in a controlled manner. This tests our processes and keeps employees' reflexes ready for a real incident. During this exercise, our incident response team completed the following items:

Mitigation

- Upon discovery, we immediately removed external contributors' ability to run unapproved CI jobs on our infrastructure via Drone’s “Disable Forks” setting.

Analysis

- Our response team reviewed all PRs from external contributors to all affected Teleport repositories looking for injection of malicious code and found no evidence of an attempted attack. - We inspected metadata from AWS buckets hosting our release artifacts for any sign of change after initial publishing. Releases from Teleport 4.4 to the latest show no artifact updates post-release. Older, out-of-support release artifacts showed some deltas from our younger startup days, but none of these updates-after-publish occurred within the vulnerability window. - We examined all Teleport Cloud access via Drone accessible credentials and found no misuse.

Remediation

- We formalized our critical security incident response policy.

- We rebuilt our Drone CI cluster, and retired the old cluster. While doing

so, we:

- Removed the ability to escalate from attacking a worker to attacking the service itself. Separate concerns now run in separate node pools.

- Developed a Drone extension that requires approval of PRs from forks.

- We rotated all affected credentials, including signing keys. If you use signed Mac binaries or our RPM/DEB repos, stay tuned for future updates about non-disruptively rolling our public signing keys.

- We educated our engineers about external PR validation and CI attacks.

- We added support for reproducible builds, so that our users can verify the integrity of artifacts by recompiling Teleport locally. (teleport#7432)

- We issued security releases for all supported versions of Teleport. (7.1.1, 6.2.12, 5.2.4, 4.4.11)

In total, the vulnerability in our Drone configuration existed between May 4th, 2020 and April 22nd, 2021, with potentially exposed secrets rotated by July 27, 2021.

Prevention

In addition to the mitigation steps taken above, we continue to work on the following longer-term preventative items:

- We will split public-facing CI from release infrastructure and internal CI infrastructure. (teleport#8268)

- We will improve the audit trails and access controls for all release artifacts. (tracked internally)

- We will replace our use of privileged DIND as part of CI. (teleport#8269)

- We will improve our reproducible builds to include more artifact types and platforms. (teleport#7889)

- We will remove the ability for Teleport’s infrastructure to access employees’ private repositories, either improving Drone’s GitHub integration or investing in a different tool.

- We’re running a sandboxed re-creation of this vulnerability as an internal capture-the-flag to build awareness of the hazards of CI amongst employees.

If there are other critical items you’d like to see included in our response, please contact [email protected].

Advice to others

Based on our experience, here are three pieces of security advice to consider when deploying CI systems:

Vet external contributions before running CI

Require a trusted party to read and approve untrusted code before running it. This may seem obvious; however, it is not default behavior for many tools. GitHub Actions, for example, lacked approval features in their initial rollout; Jenkins and Drone require plugins to add this functionality.

When implementing approval, be careful to require re-verification each time the code changes, and avoid races related to fetching a git branch or tag that could change between approval and execution.

Reduce blast radius

Assume part of the system will be compromised at some point, and strive to keep the initial compromise from compromising the entire system. For instance, the service and jobs cohabitate in the default Jenkins setup. This creates a path from hacking a CI job to compromising the Jenkins service itself. Close this hole by running jobs via agents on a separate machine. If you use an orchestration substrate like Kubernetes, be sure to separate at both the container and machine level. Contemporary containers aren’t a strong sandbox.

Furthermore, as the recent Travis CI vulnerability shows, CI vendor security isolation is often insufficient (for example: separating release secrets vs PR secrets) . Examine all the secrets and access that a CI system has as well as potential pivots. Consider the worst case for each workflow, and design to minimize impact.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

Review CI and release architecture for security

Often, CI is seen as a secondary function — especially at young companies — but the systems and habits established early may live on for many years. Treat CI and release security the same as you would your product and customer’s security, they may be one and the same.

At Teleport, this means staffing full-time engineers, completing Requests for Discussion for significant changes, and hiring external security experts to audit our CI, just as we do for our product.

Wrap-up

We hope this write-up has been helpful — understanding how an open-source security company can make mistakes, proactively find issues, and improve security posture. We learned much in the past months, and have substantial work ahead of us.

Although this vulnerability was not exploited in the wild and had no impact on customers, we choose to disclose it because transparency and openness are core to our engineering team. Security is built on trust, and trust is built upon open communication.

If you have questions or concerns about how this vulnerability impacts your use of Teleport or if you know of other vulnerabilities at Teleport, please contact [email protected].

Thanks to Kevin N., Russell J., Gus L, and Adam G. for their contributions to this post.

Tags

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter