Home - Teleport Blog - What the Twitter Hack Says About Your Company

What the Twitter Hack Says About Your Company

Cyber threats are a feature of our everyday digital life. Most of us have been the victim of one of these attacks, even if we are unaware. The larger hacks make it into the public consciousness, like Equifax, Ashley Madison, Capital One, and more, but we rarely hear from Silicon Valley tech companies. While not infallible, companies like Twitter or Facebook are still not held to strict standards for customer safety.

Sure, these companies have pioneered innovation, employ some of the world’s best engineers, and are well adapted to the Internet, but they have historically been sloppy with user accounts and data. So, when I heard about high-profile accounts like Barack Obama’s and Elon Musk’s had been hijacked, I wasn’t shocked, but I knew something had gone badly wrong this time around. And then, a week later when the next 2020 news cycle started, I forgot about it. Fortunately the damage from this hack was mostly to Twitter’s reputation.

It wasn’t until I came across a recent report from the NY Department of Financial Services that my interest was reignited. Having now done a thorough post-mortem, it is clear to me that Twitter’s hack was in no way unique. The flaws that exposed Twitter are commonplace throughout all companies. It’s likely that even your company suffers similar structural flaws, like relying on a VPN or poor logging hygiene.

Twitter Post-Mortem

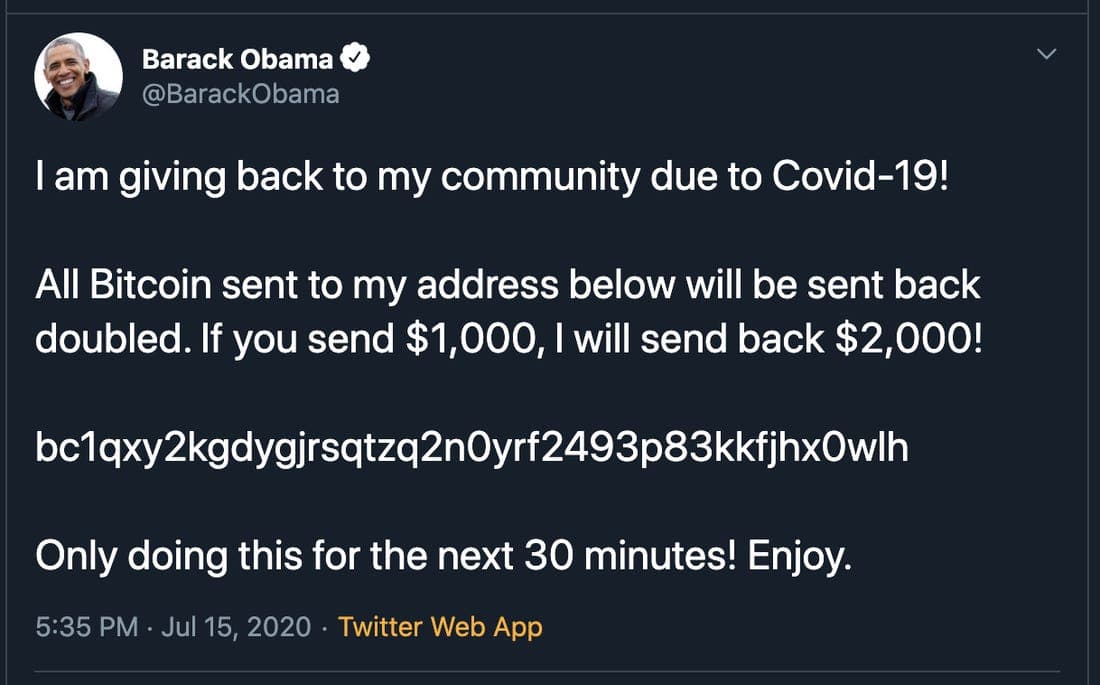

In the middle of July this year, over a span of 24 hours, a number of Twitter accounts posted similar messages, offering to double the amount of Bitcoin that was sent to a specified wallet.

This was actually the final stage of a sloppy plan slapped together by a teenager fresh out of high school. Between when Twitter was originally targeted and @elonmusk tweeted, a lot had already happened.

Stage 1: Obtaining Credentials

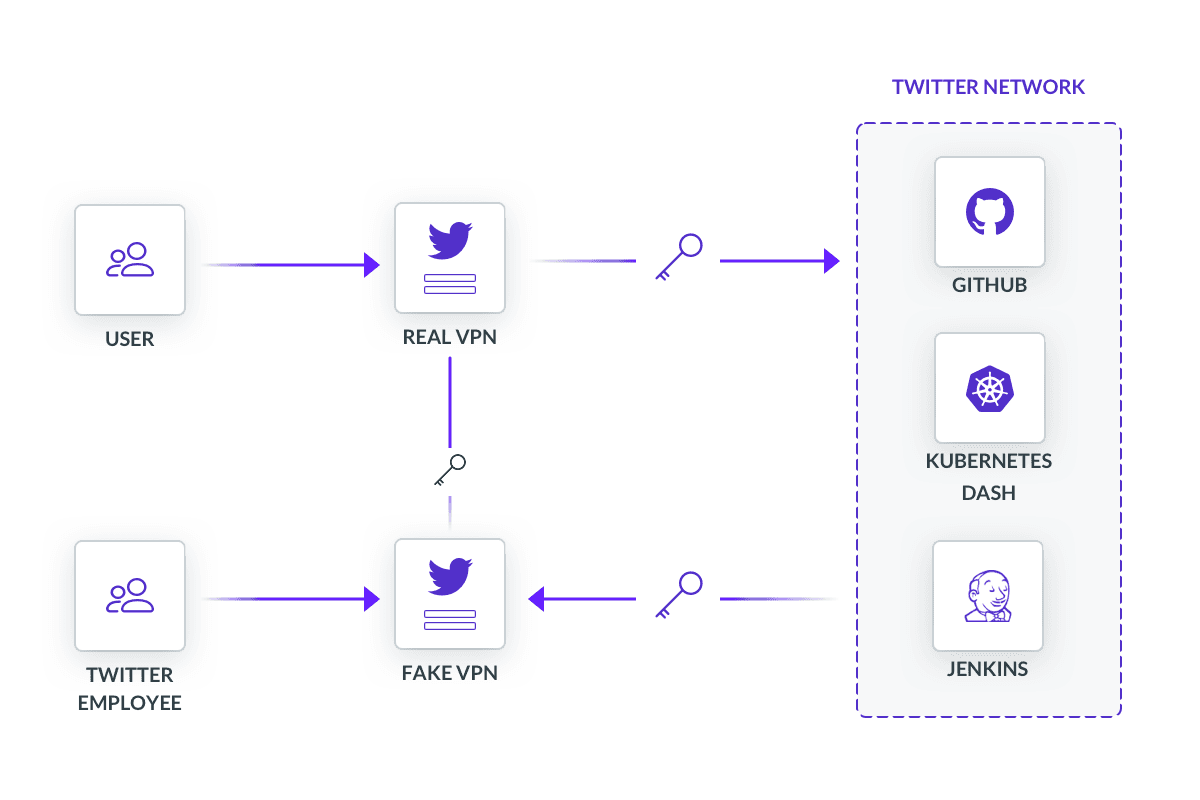

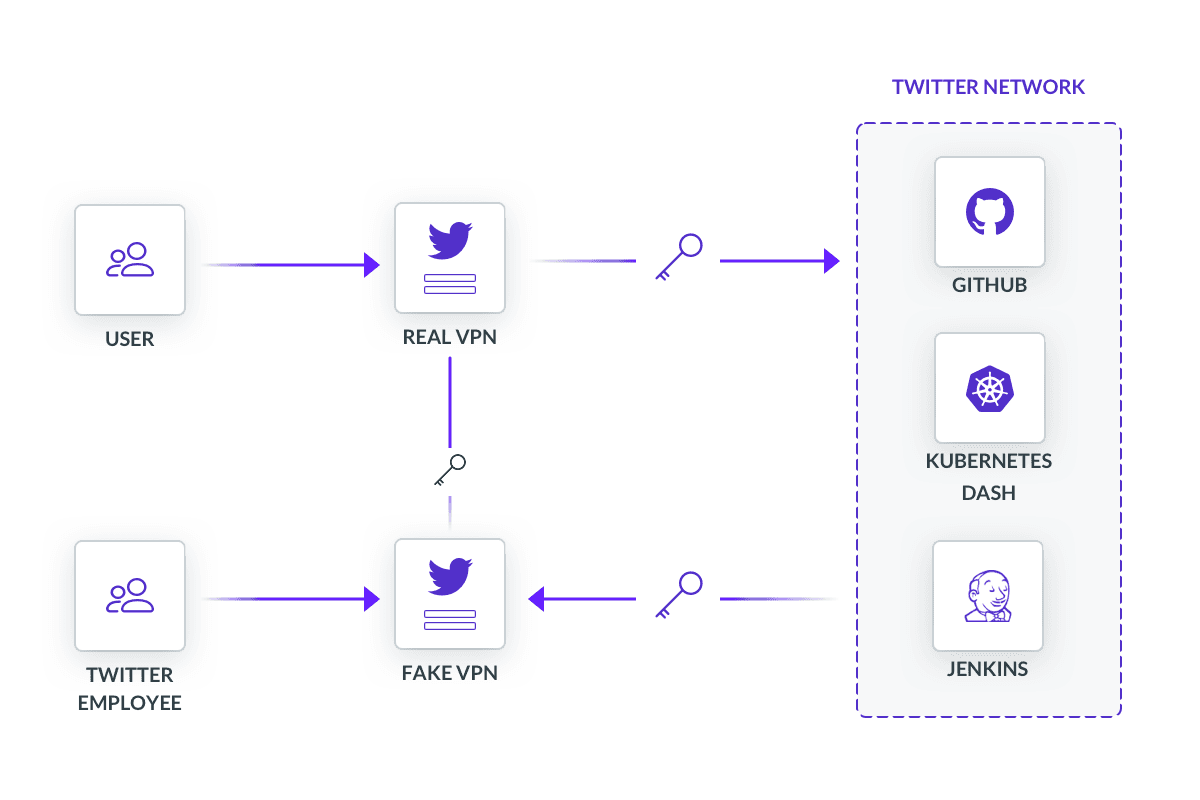

The perpetrator, who goes by the online alias Kirk, had correctly guessed that Twitter had an internal administrative tool to manage user accounts, perhaps for account support. To get access, he had to impersonate a Twitter employee, which meant finding the right employee to steal login credentials from. Simple in theory, but also simple in practice. No sophisticated technology or techniques were involved here, just some clever social engineering, credibility, and a fake virtual private network (VPN).

Kirk had to identify his target - someone that would have access to Twitter’s internal applications. Social reconnaissance does not require a degree. At minimum it requires scouring social media apps for useful information. Kirk also needed a plausible reason to talk to any of the people he’s identified. His context was the abrupt transition to remote work by COVID-19. For security teams, that meant forgoing many of the traditional defenses found in corporate or device. VPNs became the default way to establish a secure channel, which subsequently increased the volume of calls to Twitter support too.

Armed with this information, Kirk struck. Unlike phishing, he employed a slightly more sophisticated method known as vishing, or voice phishing. Kirk impersonated Twitter’s IT Support Desk and went down his list, calling to help troubleshoot a problem with their VPN. Upon trusting Kirk, the target was directed to a website he had mimicked to look like an internal VPN portal. Naturally, this site was phished.

Twitter, like all other smart companies, enforced multi-factor authentication (MFA). But, in this case, the employee submitted their login credentials and MFA code to Kirk’s fake website who simultaneously submitted it to the company’s actual VPN portal. Fortunately for Twitter, those who made it to this step had the presence of mind not to put in the code. Unfortunately for Twitter, there was one who did.

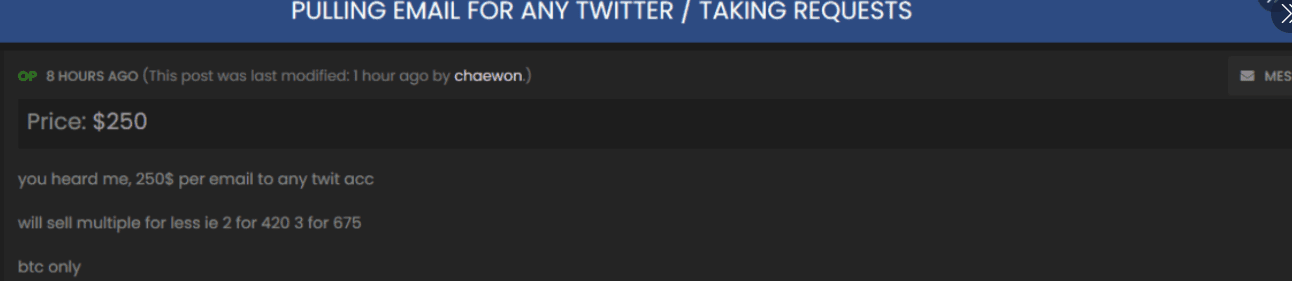

Stage 2: Selling Accounts

Kirk’s first scheme took place on a shady digital marketplace, OGUsers, where users traded Twitter, Instagram and Fortnite accounts for Bitcoin. It was a perfect place to hawk stolen goods. For sale was access to “OG” accounts with short handles that had been claimed by users in Twitter’s early days. Handles like @6 and @B were status symbols in certain circles, selling for thousands of dollars on secondary markets like the one Kirk frequented.

Kirk and his accomplices advertised their services on OGUsers in exchange for Bitcoin. When he got a request, Kirk would use Twitter’s internal tool to:

- Reset the on-file email address to what the buyer specified

- Disable 2FA authentication, sending an event notification to the new email address

- Finally, reset the account password, which was also went to the new email address

In this way, Kirk was able to covertly auction off a number of OG twitter accounts and raked in thousands of dollars.

Stage 3: The Bitcoin Scam

Around 3pm EST on July 15th, Kirk took his operation up a notch. He stopped going after accounts and targeted their followers. Starting within the crypto-sphere, he tweeted an invitation to send Bitcoin to his wallet.

Had Kirk kept his scope narrowed to the world of cryptocurrencies, it would likely have not made it to the general populous. But just as people on the east coast began to wrap up their work days and scroll through Twitter, Kirk cast the widest net he could and tweeted as influential political figures, companies, and celebrities alike. Over the next two hours, Kirk brazenly reached the majority of the Twitter-verse through the accounts of Barack Obama, Elon Musk, Joe Biden, Kanye West, Apple, Uber, and others.

Hours after Kirk’s third act had begun, Twitter vaguely acknowledged the incident, starting a thread that provided periodic updates while Twitter’s security incident team did damage control. Aside from taking down the tweets, their preemptive measures included restricting verified accounts from tweeting, preventing any password changes, and locking accounts that had passwords changed within the previous 30 days. Internally, they locked down all but critical access. Nearly three hours later, the worst was over. Twitter had mostly regained control, but not before Kirk made off with a sizable six-figure payday of 110,000 USD.

The Damage Done

The damage was mostly monetary, but the implications of what could have been done was alarming. Kirk was a teenage kid that probably wanted to buy himself a Lamborghini. But with the access Kirk had, he wielded the power to do some very, very bad things. Overall what happened was trivial compared to the hypotheticals. 130 total accounts were targeted. Of those, 45 had tweets sent by the attackers, 36 accounts had their inbox read, and 8 accounts downloaded archived account data. Intangibly, Twitter’s response to lock accounts meant that emergency services, like a local National Weather Service office in Illinois could not alert its followers about an incoming tornado. No doubt other institutions faced similar challenges, ranging from minor inconveniences to life-saving information.

Ask a network security engineer and they may tell you that this was just a MFA problem. Twitter could have avoided this entire mess if they had just used channel binding! A secret shared between Twitter servers and the employee’s device should have been bound to the underlying TLS connection they were using to speak. That way, when Kirk tried to use a valid MFA code, his device would not know the shared secret, rejecting his request. But this misses the forest for the trees. A hack of this nature should not have brought Twitter to a halting crawl, there should have been a host of security measures in place. But instead, Kirk had exploited conscious choices that weakened Twitter.

“There was a systems-level failure. The whole thing should not have happened. The issue isn’t that someone got phished; it’s that once they got phished, the company should have had the right systems in place.”

Despite how genuinely advanced Twitter or any other tech company is, systemic failures will always lower the bar for someone to make off with company secrets. Investigating how Kirk wreaked havoc reveals weaknesses that are not unlike some that your company may have today.

You’re Not Identity-Aware

“Identity-Aware” is one of those terms framing two concepts that usually don’t go together, like ride-sharing or tweetstorms. What it really means is making decisions based on information that identifies. Who? What role? What team? Policies take multivariable contextual data to enforce the right rules per request. This isn’t some novel revelation. Varying degrees of access controls have existed for years - passwords for email, public keys for servers, yubikey for computers. Tokens, certificates, and other secrets are necessary for protocols, but they cannot identify specific users because of how one-dimensional they are. Access control becomes an exhausting exercise in juggling secrets of different rarities.

Twitter did not make good identity-aware decisions. Kirk’s spread was 1,000 Twitter employees that could use the tool he needed. A full 20% of the company was a feasible target. Those who provided account maintenance, content reviews, or terms of service enforcement were all the same. A healthy culture of trust at Twitter had undermined its security policies as well.

"We had to assume everyone was untrustworthy."

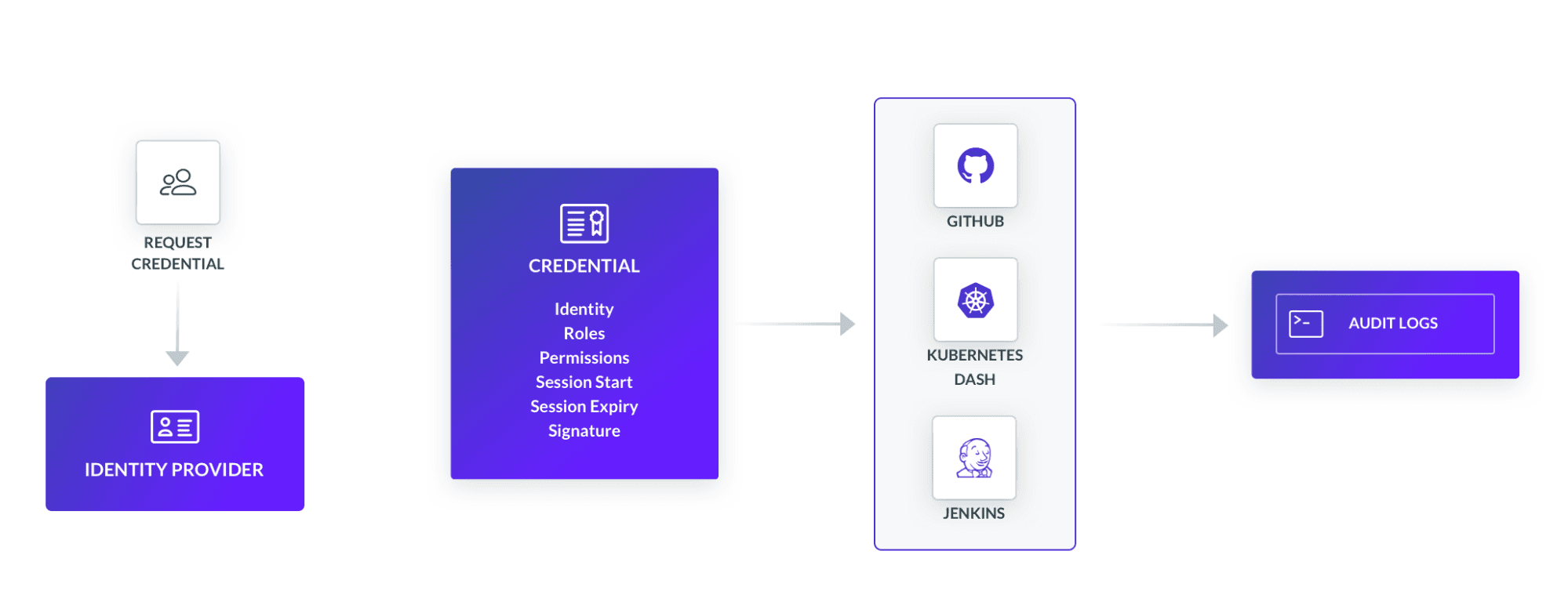

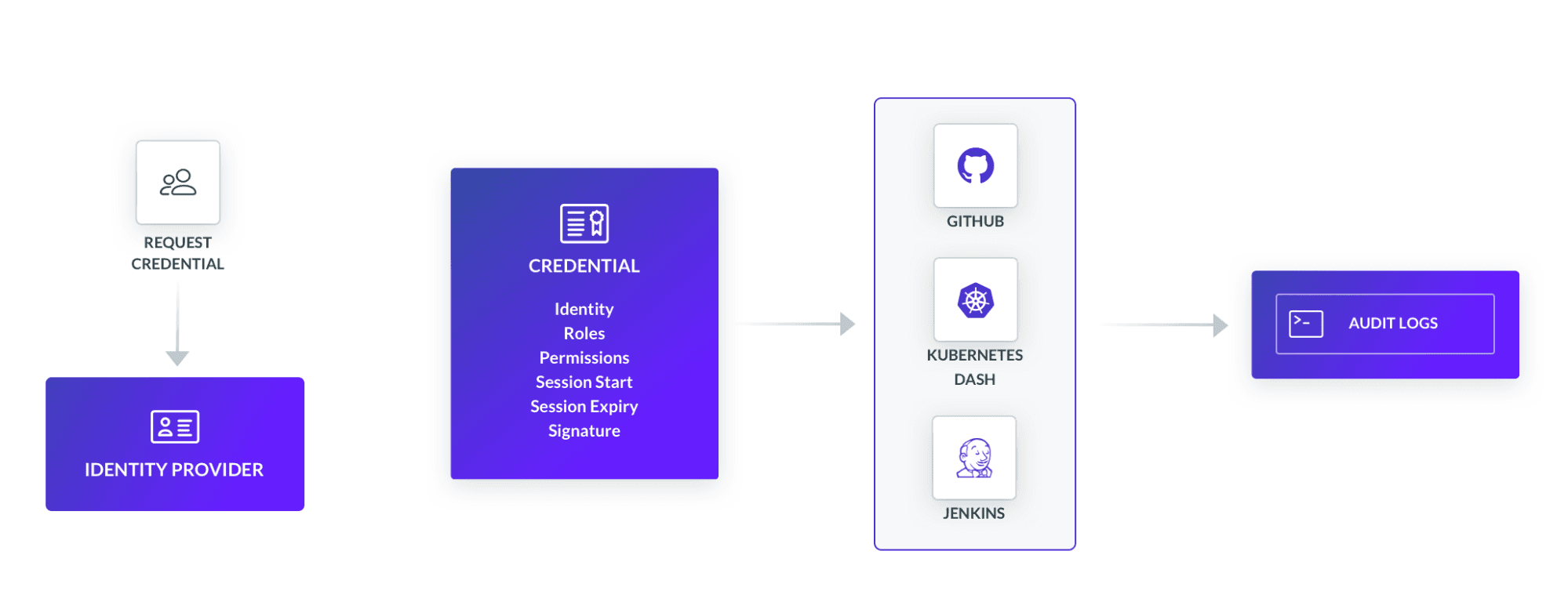

Making identity-aware decisions is not complicated. Much of the heavy lifting has already been done by identity providers (IDPs) like Okta or Keycloak. IDPs aren’t just for single-sign on, they also contain actionable data by consolidating all identity functions into a central location. The other half of the equation is programming access policies using identity data. Policies that know Jane from team:content with role:review does not need to be able to reset account passwords or Alex on support shouldn’t be able to blacklist accounts.

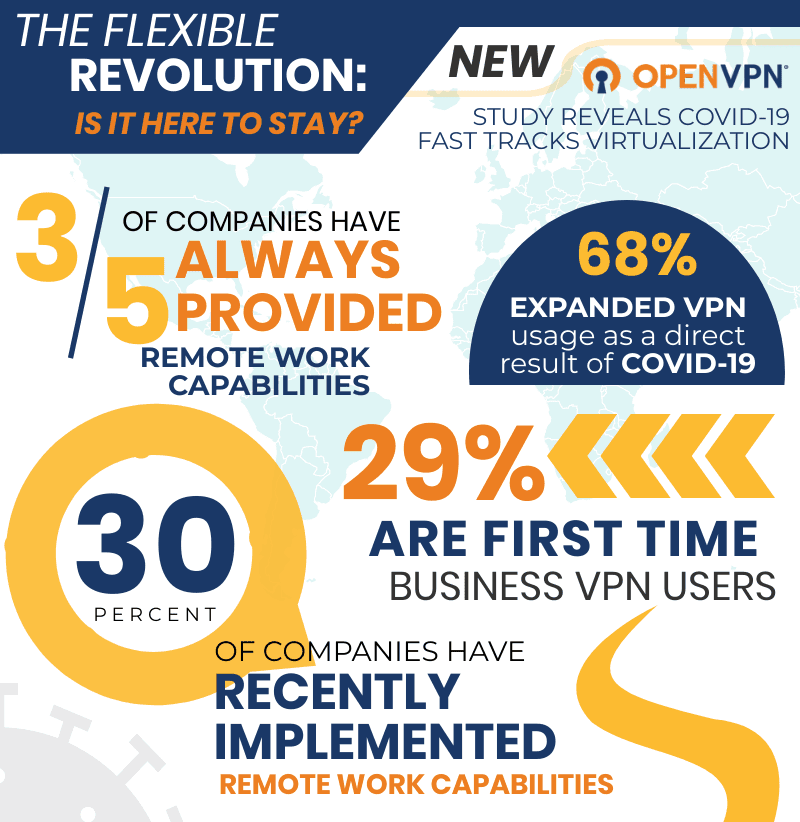

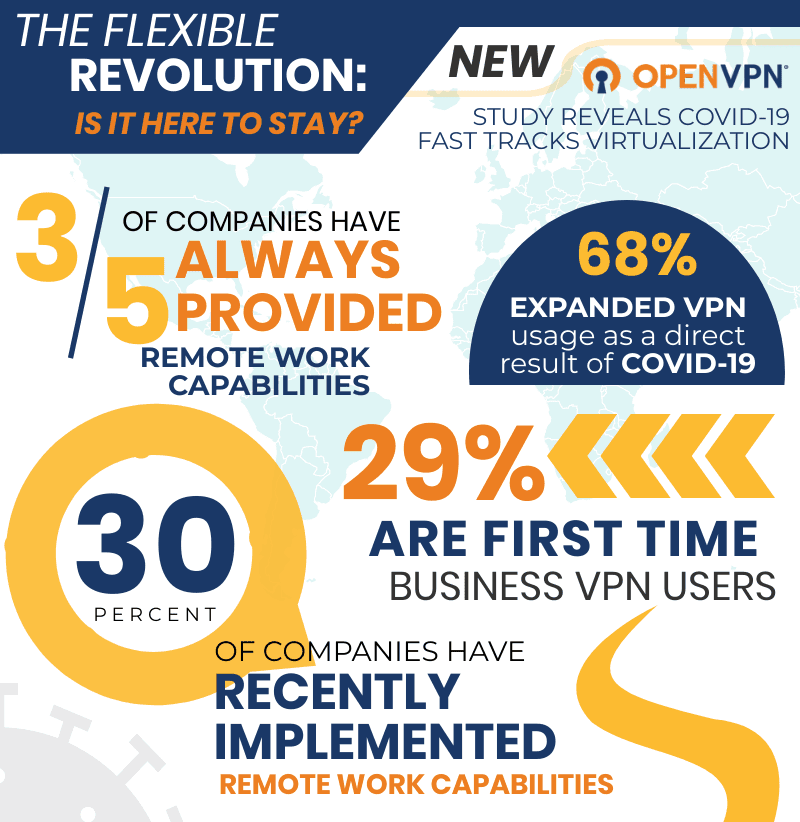

You’re Using a VPN

VPNs are one of the simpler networking tools. They securely connect one endpoint, say a computer, to another, like a server, over some existing network connection. COVID-19 has thrown a spotlight on VPNs, emphasizing desirable properties like confidentiality and authentication.

What they can’t do is recognize who is sitting behind the VPN. Once a user has logged in, the ability to trace the user’s actions is muted, reduced to a security group and a network policy. As long as the correct sequence of steps are followed, nearly indistinguishable access is given to a broad range of tools and apps.

Once again, it comes back to identity. It’s the same reason that 1,000 employees were given the same level of access. Because after making it past the perimeter, there are very few checks on who gets to do what. Thing is, VPNs aren’t the safest way to remotely access a Kubernetes pod, Prometheus database, Grafana dashboard, or anything within the sprawling open source landscape. Ten years ago, maybe. But today there’s an app for that.

Cloud infrastructure runs fluidly. Operations are abstracted and isolated into containerized services that communicate with one another. Why not have a discrete component for authentication and authorization that can communicate with other services, like Twitter’s admin tool? One that, on a per-request basis, processes identity information to enforce access restrictions to any company resource - code repos, CI/CD pipelines, controls panels, etc. The exercise here is to feel comfortable exposing work apps to any device, anywhere. Google figured it out years ago with BeyondCorp.

You’re Ignoring Your Logs

Data exhaust is a natural byproduct of the many layers of software we run in today’s cloud. In the cloud, servers spin containers up and down all day, each creating its own brief flume of logs from across the IT stack.

The upfront value in collecting logs is not always apparent, but they play a big role in reactive security models. Having historical information provides a map to locating a breach. With identity fields like user and login included in event data, incident response teams can work quickly and minimize disruption to other business functions.

Twitter did not have a sturdy SIEM system to catch their freefall considering the drastic measures they took. Broad gestures like booting every employee off the internal VPN, severely revoking employee access, and locking accounts indicated that Twitter lacked information to move with precision.

“Alex Stamos, the former chief security officer of Facebook, says he’s surprised that a phishing scheme of customer service reps could lead to a total shutdown… it would have been much better for Twitter to just analyze its logs and shut down the accounts causing all the trouble.”

Alex Stamos - Former CISO at Facebook

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

You’re Not Ready for an Audit

Data privacy and cybersecurity compliance is the cost of entry into many markets. HIPAA, PCI, FedRAMP, SOC2, are all sector-specific regulations. Privacy and security policies like these are trending across people and governments, like the monumental California Privacy Rights Enforcement Act passed earlier this year. Expect to see broader federal standards in coming years as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and other institutions become more active.

Many compliance requirements are consistent through all these different frameworks.

Employees should have access to only what they need, planned responses to data breaches, and audit control standards that require logs be stored for some number of years. In fact, a 2019 FTC filing is modeled on a New York cybersecurity law that would have failed Twitter.

Navigating these rapids requires the right equipment. As the tech industry matures, the way it is governed will change too, just as it has for banking, oil, and health. To stay ahead of the curve means not only designing systems that will be compliant, but using software tools that support the effort, whether purchased or built in-house.

Conclusion

Twitter was not hacked by a sophisticated operation coordinated by a nation state. It was hacked by an average teenager who was too young to have his own license. Twitter exposed itself to such low hanging fruit by neglecting important system-wide constructs, like authentication and authorization.

Many other organizations suffer from the same shortcoming, while others have stayed ahead of the curve, employing the best security practices that modern tools can afford. If you think you may fall into this former camp and are interested in learning more about secure access to applications, we’re hosting a webinar on November 19th at 11am PST. We hope to see you there!

Table Of Contents

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Tags

Subscribe to our newsletter