Home - Teleport Blog - SSH Certificates Security - Feb 18, 2021

SSH Certificates Security

SSH Access Hardening

SSH certificates, when deployed properly, improve security. A half-baked access system using certs is more vulnerable than a public-key-based one if a user or host gets hacked.

SSH is hard. Our team learned this at Rackspace, a large managed hosting and cloud provider. We started with deploying public keys to every server. We added a jump server with a second factor login to prevent hacks using stolen keys. Soon, infosec team asked us to log into a web portal to match SSH logins with emails. Evolution does not produce the most efficient result, and our system did not turn out great either. We were missing keys on some servers and found stale keys on others. No one liked login screens popping up multiple times a day. We received only one one-time password token, and some folks pointed their home webcam to it.

In 2015 we left Rackspace to build Teleport — a unified access platform for infrastructure, and we started with SSH. We chose SSH certificates as the main cryptography engineering primitive. Since then our customers and open source users have deployed Teleport at most impressive systems, and Teleport went through several security audits.

I would like to share some of the lessons we learned with you. We will start with the SSH authentication basics, dig into SSH certificates and learn what it takes to build a secure SSH certificate-based authentication.

SSH Public Key Authentication

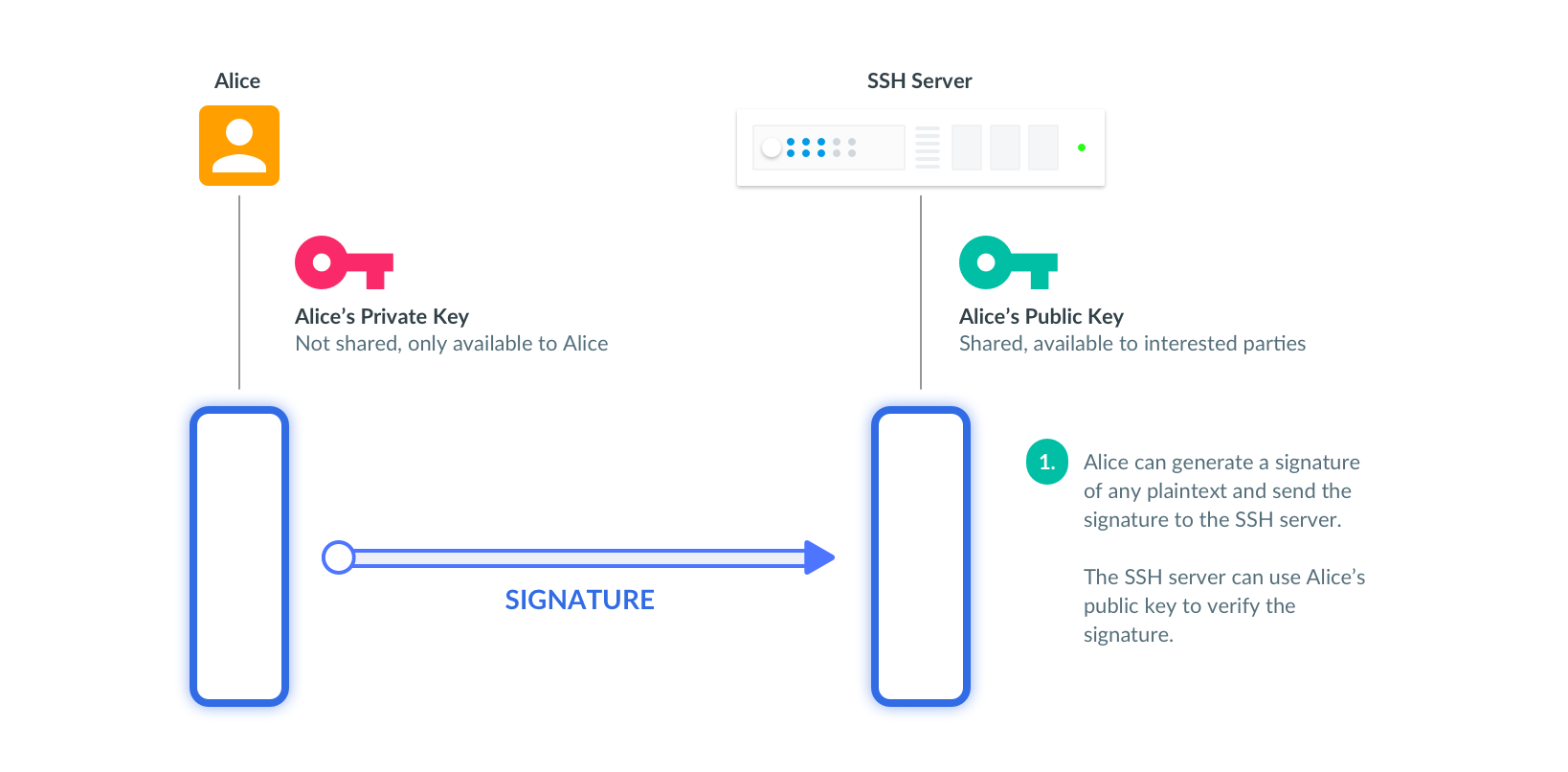

An SSH public key is distributed openly, and anyone holding it can verify messages signed using its private key counterpart.

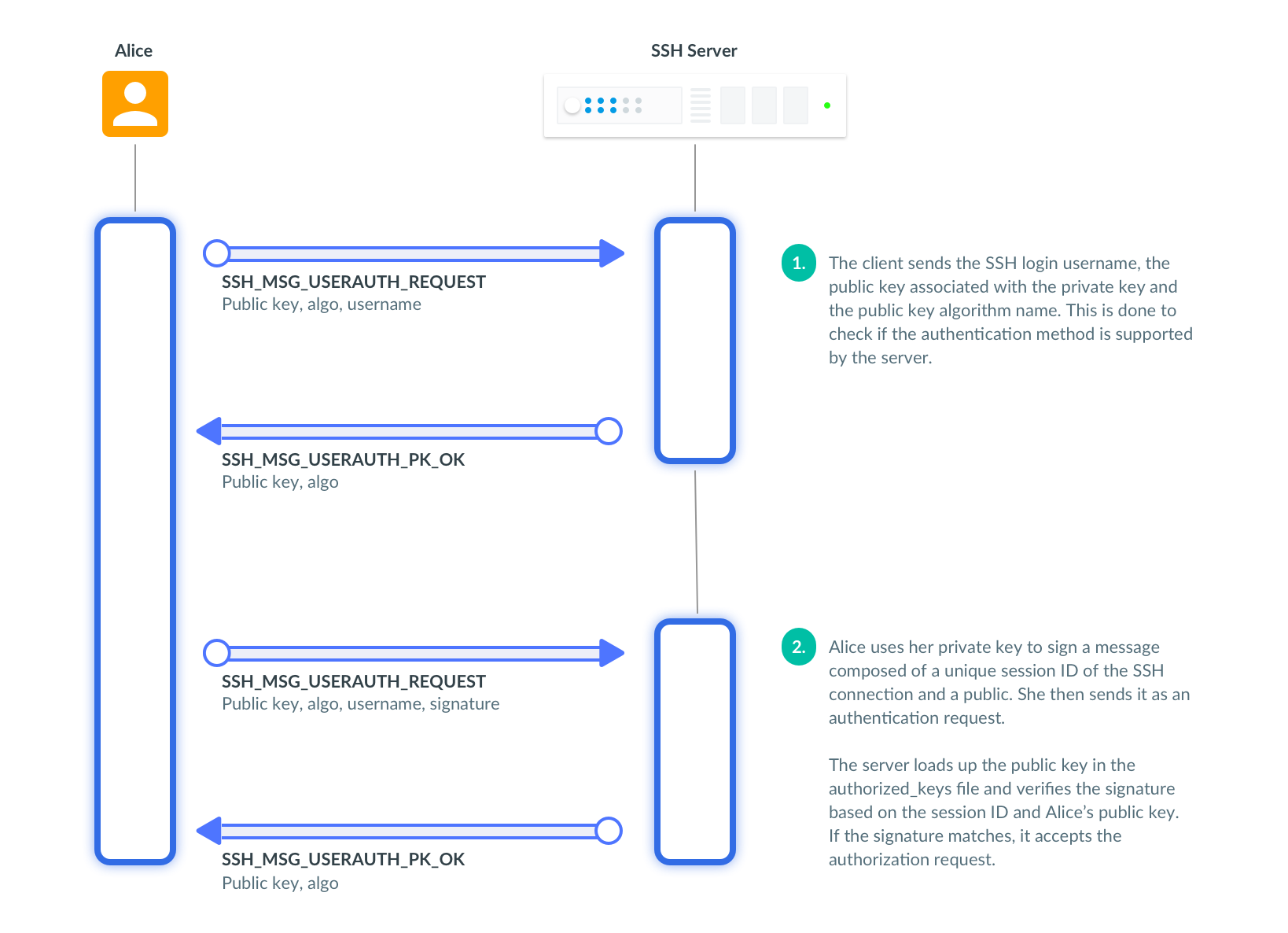

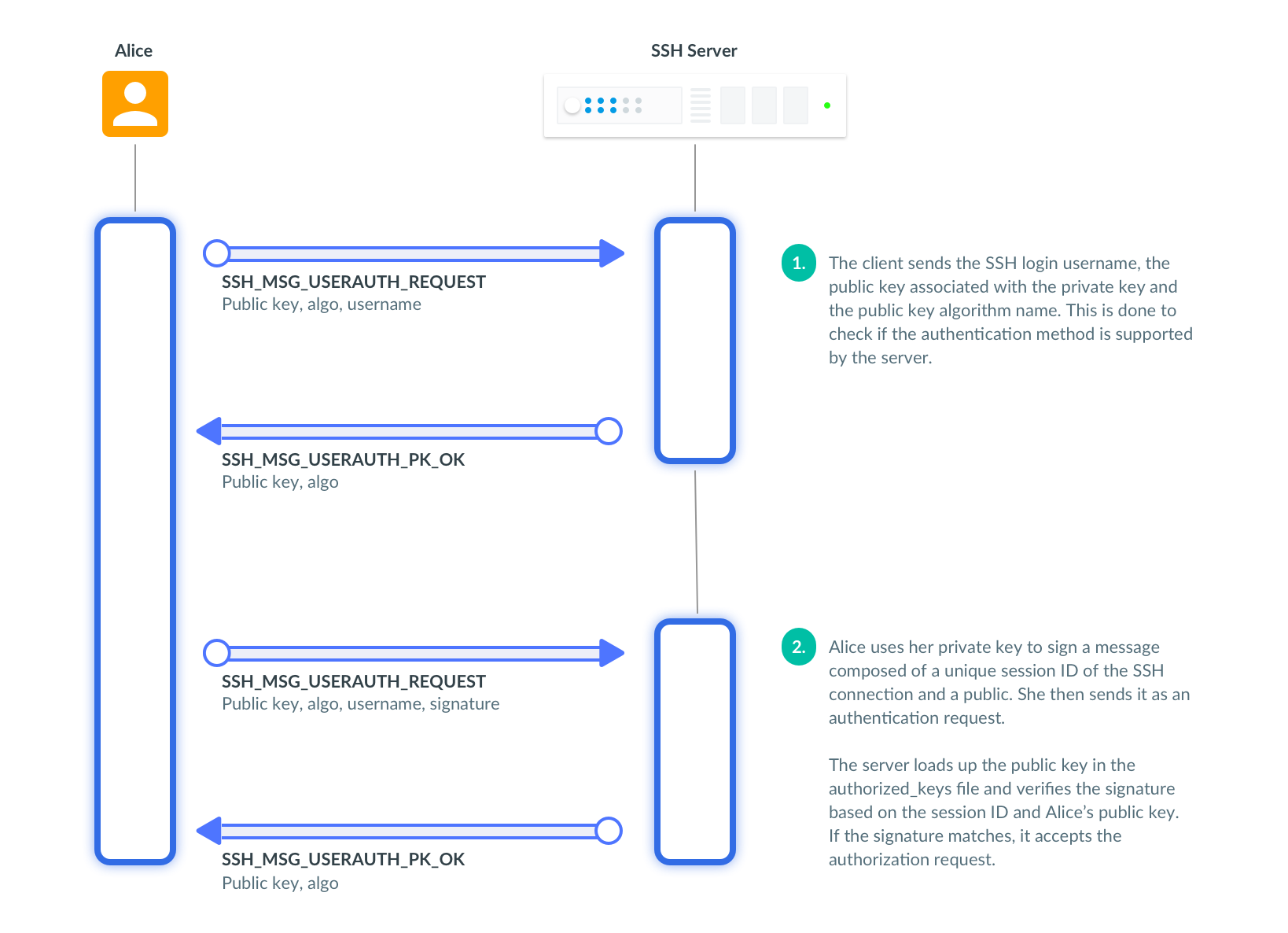

An SSH server generates a random string — a challenge — and asks a client to sign it. The server verifies clients' signature to prove that the client has the private key associated with the trusted public key. Here is how it looks on the wire:

Public keys constitute a solid way to authenticate and are used to secure both Web and SSH.

The problems with public key authentication are caused by key management: trust on first use (a.k.a. TOFU) and rotating and revoking trusted public keys.

Trust On First Use

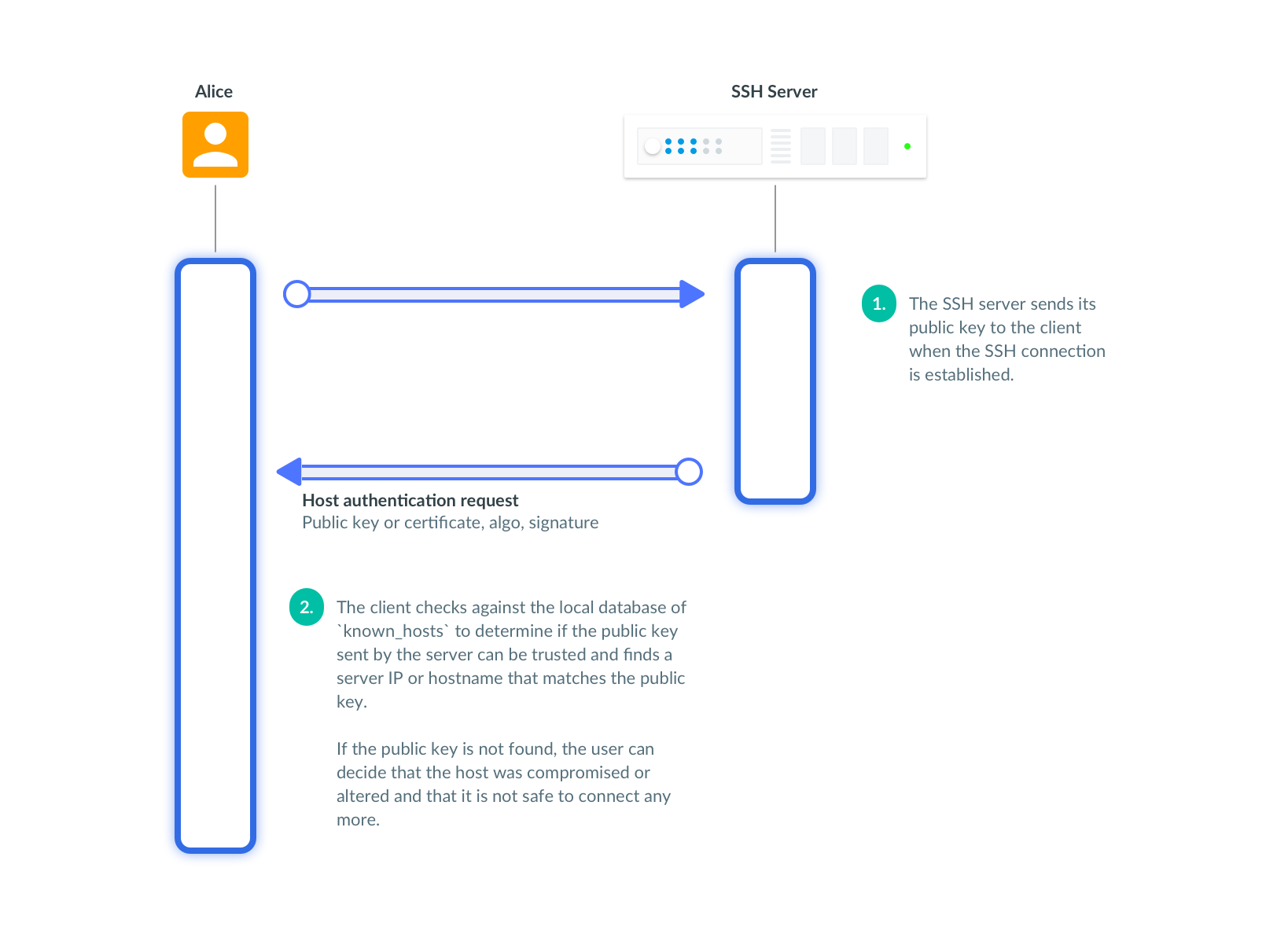

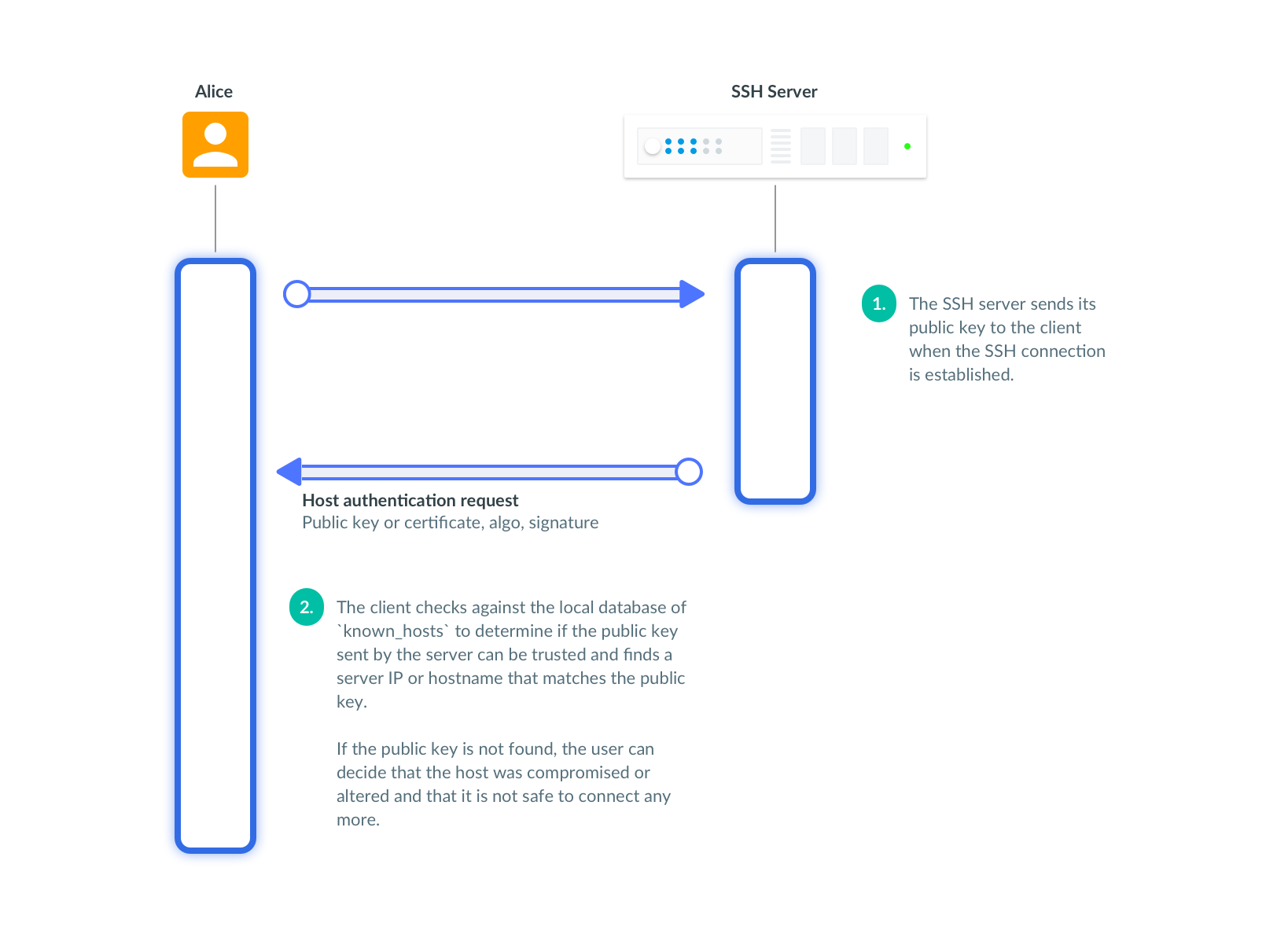

When an SSH connection is first established, an SSH server sends its public key to identify itself to a user.

The user can accept the public key offered by the SSH server and assume that the host is trusted if the user connects to it first time. This authentication scheme is called "trust on first use" or TOFU.

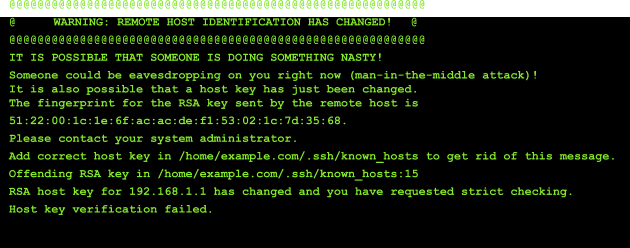

If the host's IP, name or public key change, the user can no longer trust this combination of the hostname, the IP and the public key.

The user sees a scary warning.

The user can alert security folks or ignore the warning by removing the old key. For cloud environments, however, an IP address and a hostname can be reused many times. Users learn to ignore those warnings, because there is no way to learn whether it's an attack or an IP or a hostname change. Let's call it TOFU fatigue.

Problems With Public Keys

A second problem of public keys for security is caused by complexities of public key distribution. Imagine a deployment with 100 servers and 10 users, where every user has 2 public keys. You have to build a system that distributes 20 user's public keys on each server and 100 public keys to every user's computer, and keep those up to date.

Directory services like LDAP are used to store user's and host's public keys. Every host runs an agent that connects to an LDAP server and updates public keys. Sysadmin folks have been deploying this Keycloak and FreeIPA pair for years.

This system breaks down at a small and a large scale. Sysadmins of small systems rarely deploy key management software. It's not worth setting up FreeIPA and Keycloak for 3 nodes. They use tools like Ansible and end up with keys going out of sync when someone loses their key, computer, or leaves the company. Sometimes, let's face it, there is no Ansible and everyone uses the same shared key.

Admins of large clusters learn that the system of moving the key around stops working beyond the 1K nodes or 100 users mark — there are just too many keys to keep track of.

SSH Certificates

SSH certificates are built using public keys and don't offer anything extra from a cryptography engineering standpoint.

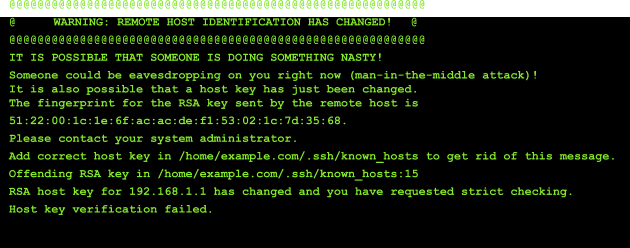

A certificate authority (CA) is a trusted party that holds its own public and private key pair. SSH CA keys are used to sign user and host SSH certificates. An SSH certificate consists of fields signed by the certificate authority.

Clients cannot modify these fields without breaking the signature.

SSH certificate authentication extends public-key-based auth and uses the same protocol messages. In addition to verifying the public key signature, SSH server will check whether the certificate is signed by the trusted certificate authority.

Solving the TOFU Problem

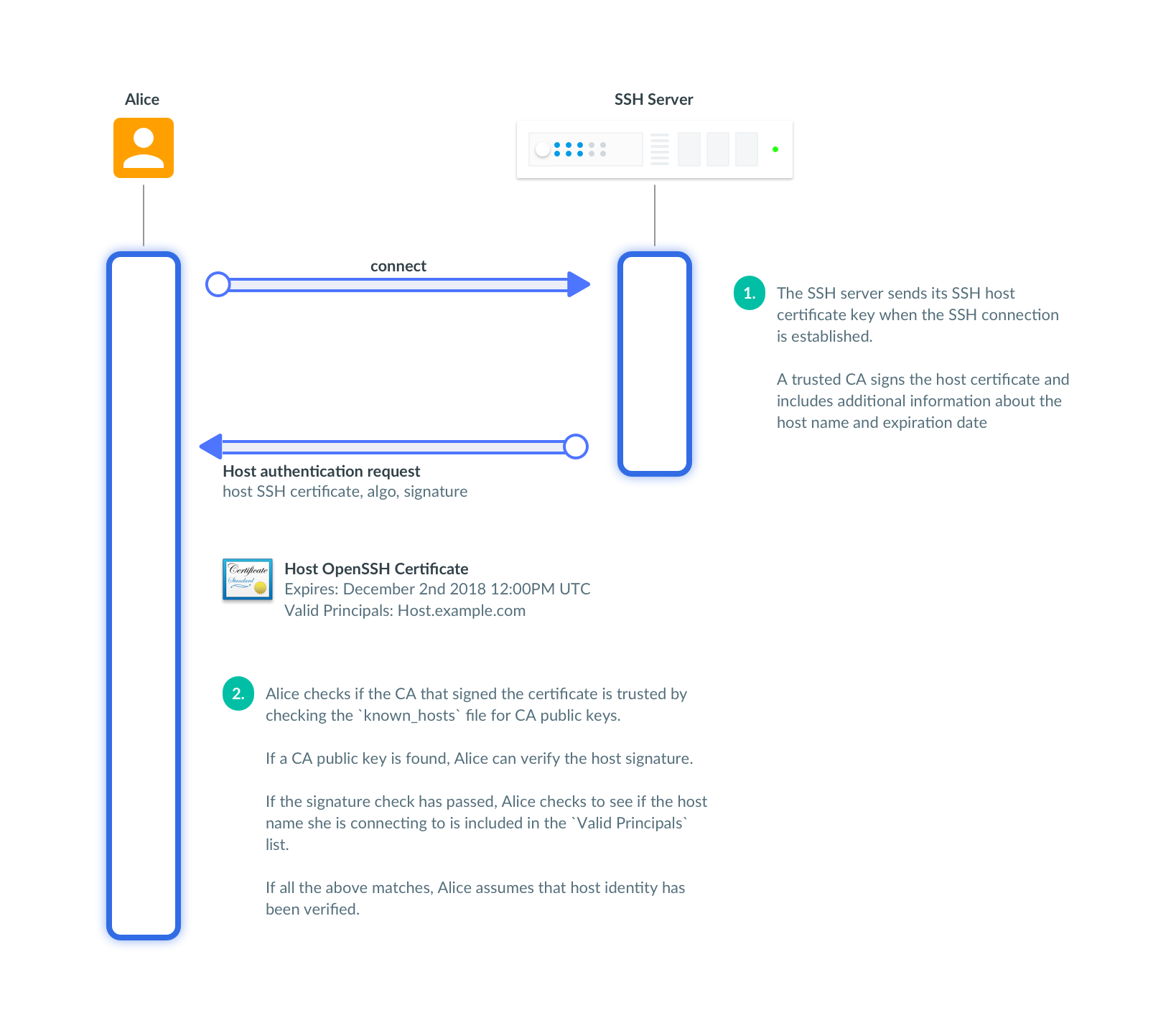

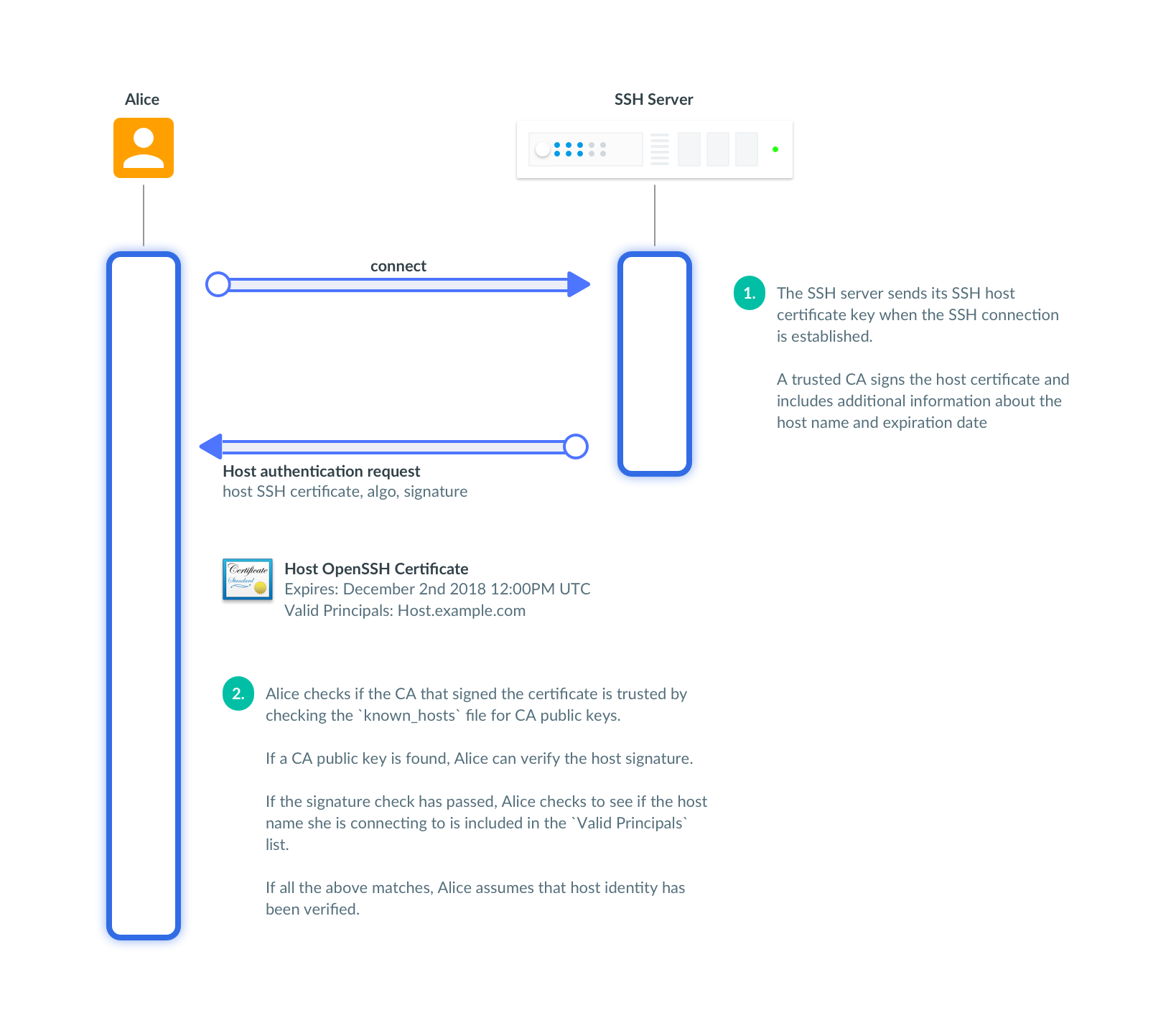

Clients use metadata in SSH certificates to verify host identities too. When an SSH connection is established, a host sends a signed SSH certificate to a client to verify the host’s identity. The host's certificate is signed by a trusted CA. It includes information about the hostname, and has an expiration date. Here Alice checks if she can trust the host's cert:

As an extra precaution, SSH clients check if the hostname or the IP matches the certificate. It makes it harder for a malicious host to impersonate another host. If the signature check has failed or the CA is not trusted, either a serious misconfiguration has happened or someone is attempting a man-in-the-middle attack.

Even if the public key of the host has been changed because the hostname has been reused in a cloud environment during instance re-provisioning, the certificate will still match; there will be no conflict between different public keys.

Sysadmins can replace the complex system of moving hundreds of public keys around with two files — a host and a user SSH certificates' authority public keys. But in practice if we had stopped at this point, we would have made SSH security much, much worse.

Compromised Users and Hosts

If a user or a host gets compromised, we have to revoke their certs. We are back to building a system of keeping track and distributing revocation lists to users and hosts. Even worse, if a private key of a SSH user or a host certificate authority gets compromised, all users and hosts certificates have to be invalidated and reissued.

This realization hits at the worst possible moment — when someone is hacked, there is no time to waste. Time works against us because with every issued cert, the potential for compromise increases. At least with public keys, we test the rotation on a regular basis. Revocation is so rare, that it could be broken for all this time and no one would notice. This problem reminds me of backup restore — you either test backup and restore regularly, or all bets are off.

Making Time Work for You

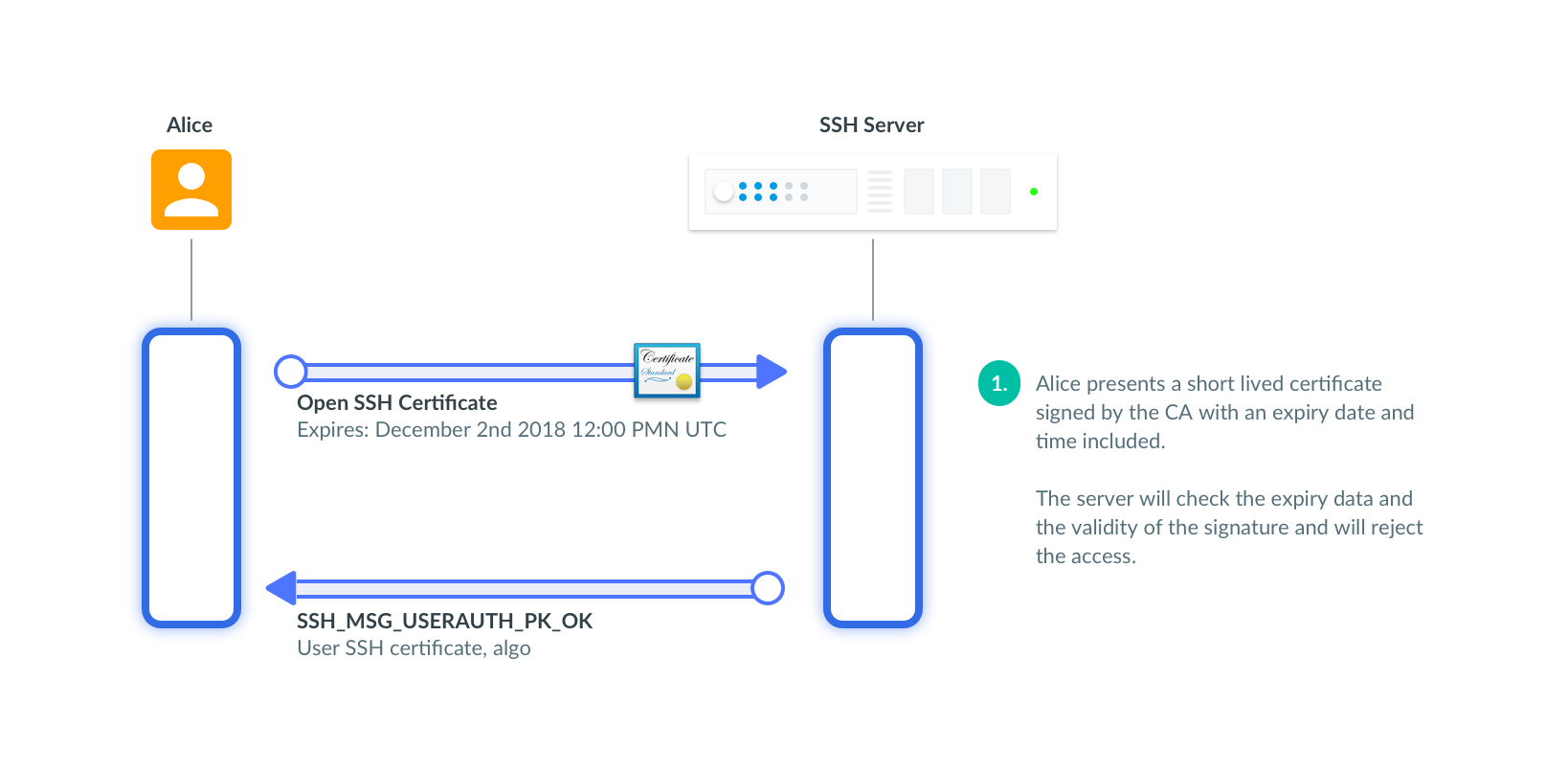

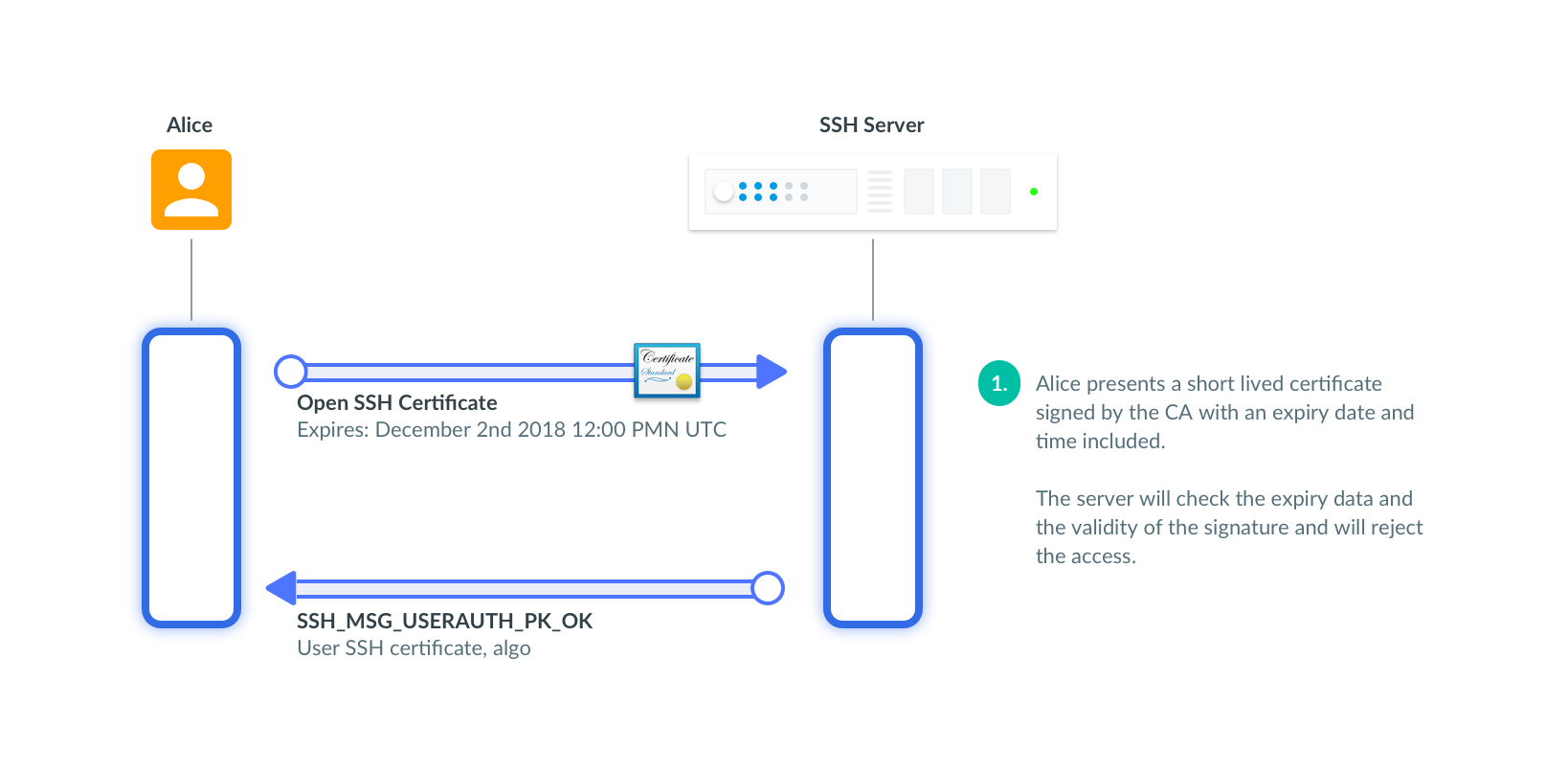

There is one trick that makes time work in favor of security. SSH certificates include an optional expiry date that can be verified by a server in addition to a signature.

Organizations ca issue certificates that are good for a few hours before they auto-expire without any action. The shorter the duration for these certificates, the better. Ideally, certs should be issued only for the duration of a session. In practice, several hours or the duration of the workday are OK too.

Instead of distributing revocation lists, we can rely on time to do the job for us.

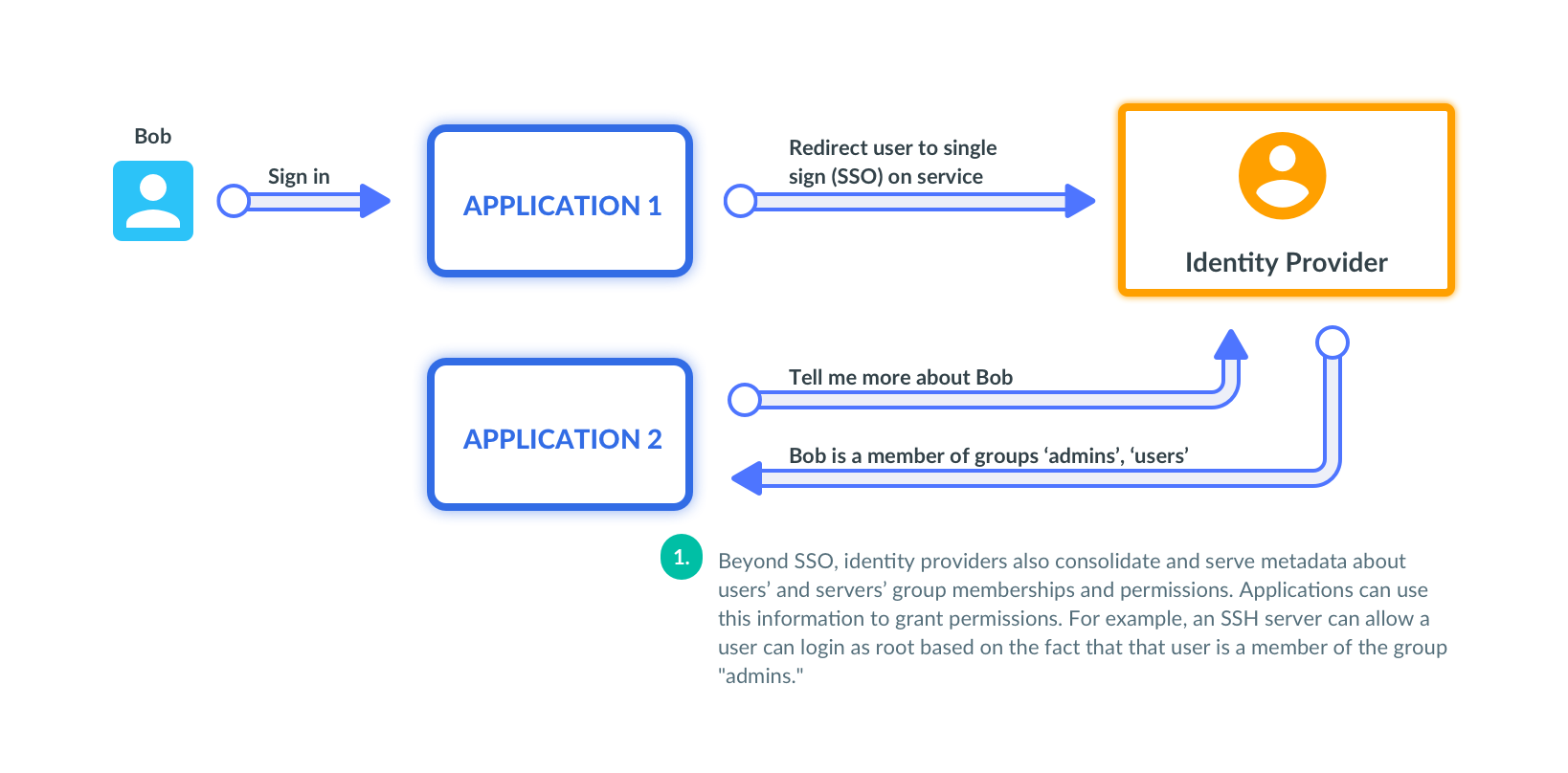

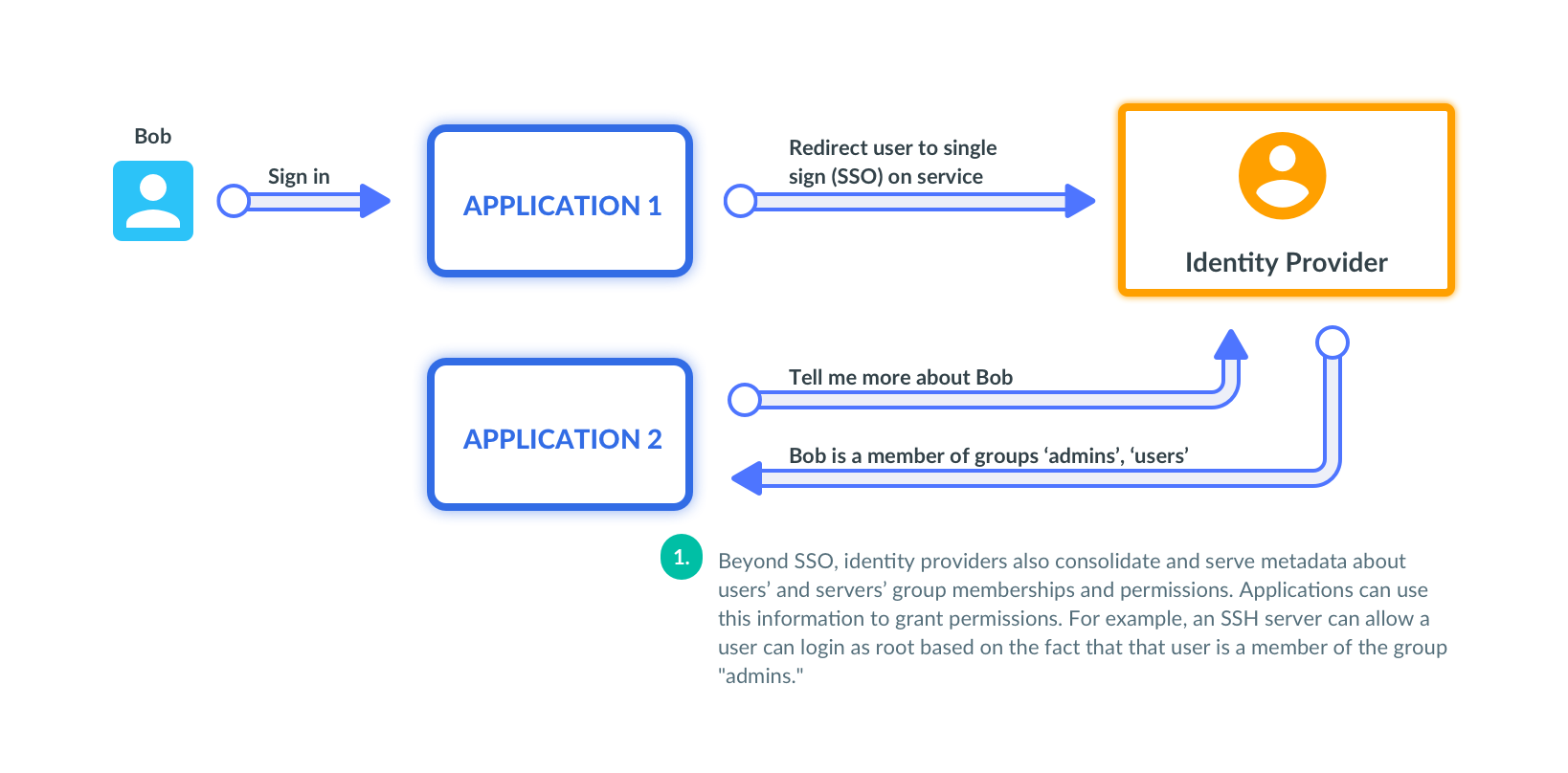

User Certificates and SSO

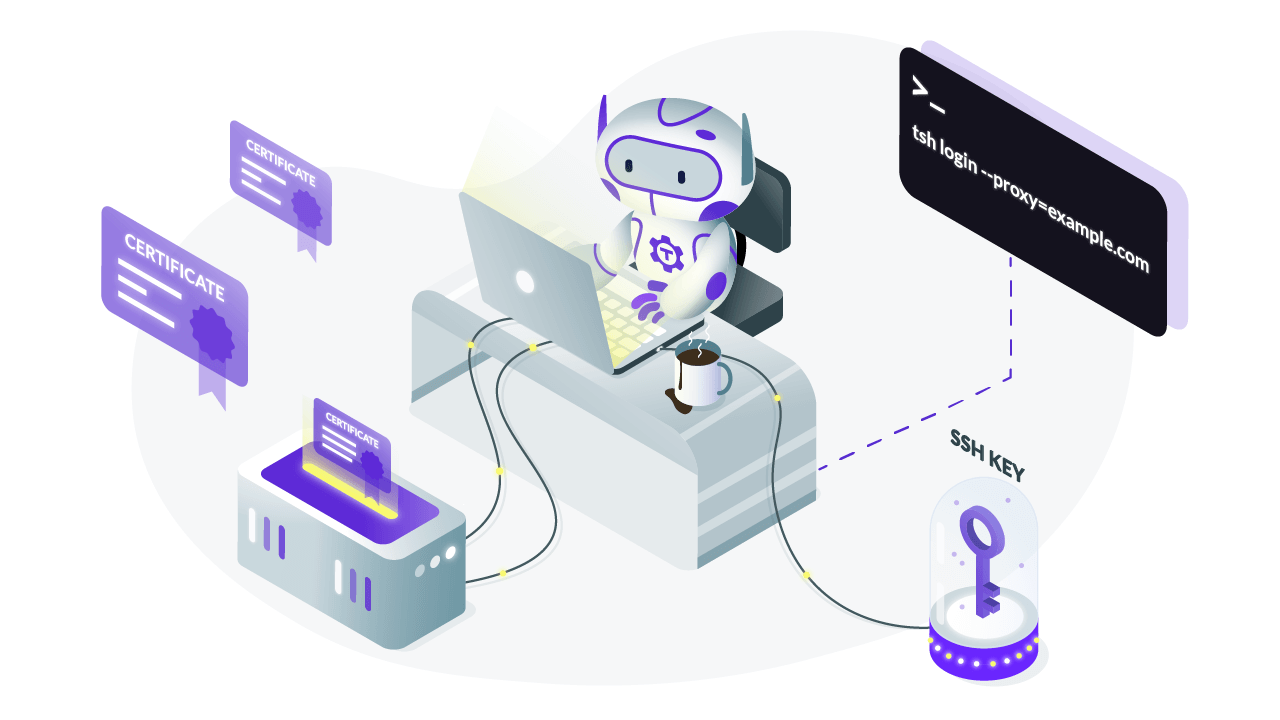

How would users get a short-lived certificate? The best way is to use SSO with GitHub, Okta or any other identity provider and get a cert. Teleport opens login screen, issues a cert and delivers it back to a user's computer:

Here is an example of Teleport's CLI tool tsh issuing a certificate

based on my GitHub credentials.

The cert is valid for 12 hours and has my GitHub identity encoded in it.

Rotate CA Keys

An attacker getting access to a private key of a certificate authority can impersonate any user or host. That's why admins store CA private keys in the most secure place possible. What happens if a user, a host, or a CA gets compromised? You'd need to replace certificate authority and reissue all certs for hosts and users. Any system dealing with certs should support this out of the box.

Take a look at how I rotate a user CA in less than a minute with Teleport:

With user certificate authority updated, all certificates issued by the old CA become invalid. It's not a problem if you use SSO; users have to re-login to get new certs. The same command rotates hosts CA as well. Instead of waiting for the compromise to happen, we should be rotating certificate authorities every day turning them from a precious secret to a replaceable commodity. Here again, time will work in our favor, not against us.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

Wrapping Up

Use certs with caution, and beware of long-lived certificates. Rotate your CA regularly and use SSO to get user certs. And maybe, give Teleport a try.

Tags

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter