Home - Teleport Blog - The full-time job of keeping up with Kubernetes

The full-time job of keeping up with Kubernetes

Updated with latest Kubernetes Release schedule as of March, 2019

What is the Kubernetes Release Cycle?

TL;DR - The Kubernetes release cycle is quarterly and unabated 1.xx major "minor" releases of "vanilla" upstream Kubernetes every three months could continue forever. You have to keep up, while also paying close attention to Kubernetes API object versioning. This relentless pace is the key ingredient in Kubernetes' domination of the distributed infrastructure world.

There is no such thing as Kubernetes LTS (and that's fantastic)

One of the questions we encounter when talking to those looking to leverage Kubernetes, especially for private on-prem DIY deployments, is simply "How do you stay up-to-date?"

This leads to a Kubistential awakening:

- Who really runs the Kubernetes community project?

- How consistent has their release cycle & quality been?

- Like Debian, Ubuntu or RHEL - does Kubernetes have a Long Term Support version -- a Kubernetes LTS?

- What sort of effort is required of a cluster maintainer or product owner to keep up each time a new Kubernetes release comes out?

- What happens when a cluster owner doesn't stay on top of updates?

- Are their plausible alternatives to inheriting the task of managing Kubernetes?

- And if the answer is simply "cloud," is it safe to use "certified" Kubernetes platforms without getting locked in?

Let's dive into a little bit of Kubernetes lore and figure out what's going on behind a project whose most recent release notes were a whopping 1,890 lines long.

Kubernetes founding story and leadership background

The initial stewards of Kubernetes within Google established a strong open community around the project from the start, taking lessons both good and not so great from the Linux kernel project, Mozilla, Openstack, Chrome, and even the infamous node.js fork.

commit 2c4b3a562ce34cddc3f8218a2c4d11c7310e6d56

Author: Joe Beda <joe.github@bedafamily.com>

Date: Fri Jun 6 16:40:48 2014 -0700

First commit

If you're coming to the party late, check out the nearly three-year-old Techcrunch article covering the Kubernetes 1.0 release. Read all the way to the end.

The effervescent open source community builder who leads the Linux Foundation, Jim Zemlin, is a veritable silicon-valley fortune teller:

I predict this technology will be too good to resist, those who are not participating today will change their mind later.

Even Bryan Cantrill, the awe inspiring Joyent CTO and long-time unix genius, expressed a mea culpa to his open source anti-pattern screed after witnessing the Kubernetes communal birth.

Another secret and largely underappreciated ingredient to Kubernetes success is the CNCF (Cloud Native Computing Foundation) releasing it under Apache-2.0, an open source license that inspires religious arguments over claims that it is an antidote to a long-brewing commercial software patent cold war among tech giants.

If you can catch Jim Zemlin when his guard is down and ask him what's so special about all this, he'll beam about the amazing legal feat of getting Alphabet, Inc to give away its nascent Kubernetes baby -- all under a patent-protected open source license!

As it has grown, the various CNCF and Kubernetes contributors have maintained a famously collaborative, open and self-introspective community with surprisingly few bad actors. Which leads us to SIGs.

Kubernetes Special Interest Group Background

Besides its genesis downstream of ten plus years of Borg at Google and a brilliant "planned community" guarded by the CNCF, another superpower driving Kubernetes is its Special Interest Group model. SIGs are basically ad-hoc groups held together by technical consensus. Their day-to-day materialization tends to follow the same patterns as the best scrum teams at leading software companies. The most critical SIGs steward the end-to-end testing and CI/CD system that faithfully enforces the Kubernetes release procedure. Interest in outlying or more esoteric SIGs ebbs and flows as work heats up and is delivered in particular areas. There is even an overall Product Management SIG staffed by top-shelf PMs.

SIGs and their working groups are interesting in the context of understanding Kubernetes relentless release cycle because the leadership, cadence and key attributes such as long-term quality are all the bumper crop of seeds sown by this SIG structure. For a great background on how SIGs interact with the larger ecosystem of corporate interests, listen to this New Stack Interview with Caleb Miles, a Technical Program Manager savant and SIG-Product lead.

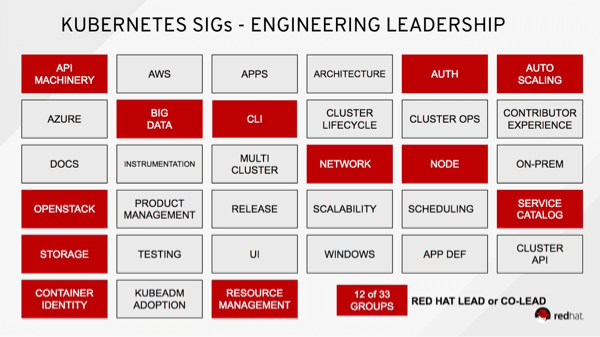

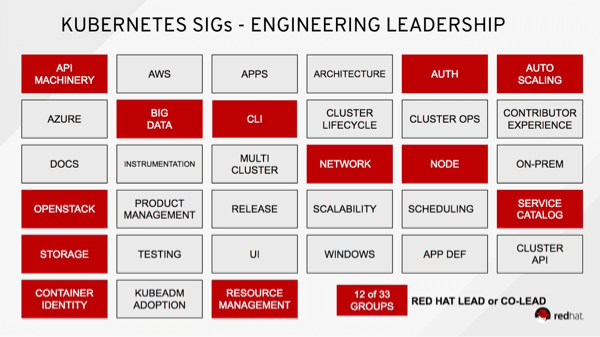

One of the great things about the SIGs is their diversity of participants and leadership. However, as is generally true with popular emerging technologies, there are always desires to consolidate power and influence roadmaps. With the acquisition of CoreOS, Redhat is now "Proud that Red Hat engineers are able to Chair or Co-Char [sic] 12 SIGs." It's not clear this is something for the community to celebrate but it will be interesting to see how this affects the project.

Kubernetes Release Versioning Background

The basic formula for Kubernetes releases is to expect big releases every three to four months. The Kubernetes Release Versioning design document has some nitty details that have boiled down remarkably well in the community melting pot. Raw pride-driven craftsmanship sets the expectations and maintains the pace of these "minor" releases. Notably, while the initial momentum came from Google, the core release team has morphed into a rolling cadrae of individuals from dozens of tech companies.

There is no mandated timeline for major versions and there are currently no criteria for shipping 2.0.0.

There is a mass critical eye toward "vanilla" Kubernetes quality and as such the collective managers of any release target are afforded wide latitude to shift dates or push back on pull requests that aren't deemed ready by the relevant SIGs. Hawk-eyed readers of the versioning document will note that there "are currently no criteria for shipping 2.0.0" and that Kubernetes has spent its public life as 1.X.Y -- where X increases once per quarter and Y ticks along at the community's collective technical whim.

Keep the nomenclature in mind: what the broad contributor community calls a "minor" release can have a drastic (usually positive) impact on the experience of operating and using live clusters.

Dan Kohn, the Executive Director née Professor Albus Dumbledore of the CNCF, admiring the swift pace of the larger CNCF landscape coalescing around Kubernetes during an interview at KubeCon Austin 2017 shortly before the release of v1.9.0 put it well: "We sort of describe this moment for the organization and the community as being the end of the beginning."

Kubernetes Historic Release Cadence

Since midsummer 2015 when Googlers Brendan Burns, Tim Hockin and Zach Loafman triggered the jump from the pre-1.x series of 0.xx tags, Kubernetes has had nine "minor" releases.

Their comments when cutting the 1.0.0 branch were prophetic. Brendan goofed the pull request and had to go twice, leaving a final comment "for realz this time!" Tim is a teary-eyed "great big LGTM" and Zach mic-drops a "Do it" after a simple inline comment on the gitMajor and gitMinor diff: "Scary."

Digging through press releases and git tags, you find an amazingly reliable adherence to a quarterly release cadence of about every hundred days.

| Kubernetes Release | Date | Cadence |

|---|---|---|

| Christening of 1.0 | 10th July 2015 | ~one year from inception |

| From 1.0 to 1.1 | 9th November 2015 | 122 days |

| From 1.1 to 1.2 | 16th March 2016 | 128 days |

| From 1.2 to 1.3 | 1st July 2016 | 107 days |

| From 1.3 to 1.4 | 26th September 2016 | 87 days |

| From 1.4 to 1.5 | 12th December 2016 | 77 days |

| From 1.5 to 1.6 | 28th March 2017 | 106 days |

| From 1.6 to 1.7 | 30th June 2017 | 94 days |

| From 1.7 to 1.8 | 28th September 2017 | 90 days |

| From 1.8 to 1.9 | 15th December 2017 | 78 days |

| From 1.9 to 1.10 | 28th March 2018 | 103 days |

| From 1.10 to 1.11 | 3rd July 2018 | 97 days |

| From 1.11 to 1.12 | 27th September 2018 | 86 days |

| From 1.12 to 1.13 | 3rd December 2018 | 67 days |

| From 1.13 to 1.14 | eta 25th March 2019 | 112 days |

Kubernetes Feature Development Process

The versioned releases of Kubernetes binary components themselves have become almost boring. The real action, and the real meat in each Kubernetes 1.x release, is in the "fundamental fabric" represented by its RESTful API.

Every part of Kubernetes uses a well defined API to communicate with every other part. Imagine this API as Kubernetes heart, wrapped by a constantly-beating set of components pumping oxygen into a declarative configuration schema. The "core" does nothing more than reconcile current cluster state with the desired state. As you radiate out to extremities you find constant API growth and refinement as an unending onslaught of infrastructure coders aim to abstract more and more traditional datacenter building blocks into consumable Kubernetes API endpoints. These additional Kubernetes features (read: APIs) leap from newborn alpha to toddler beta stages in random spurts driven by contributor zeal and larger community interest.

The founders of Kubernetes specifically designed the API versioning and deprecation standards to deal with this constant evolution. Similar to the release versioning document, there's an even longer policy around what developers and end-users should expect as features traverse their palpably awkward "tween" stages.

This is all to say, what matters in each Kubernetes release isn't the release itself, but the nuanced details of what APIs have gone from "alpha" to "beta" to "stable." If you're wearing a t-shirt with a Kubernetes logo on it right now, you probably even tear open the changelog to see sub-level version bumps or which exact parameter fields have been added or removed.

While there have been some notable false starts along Kubernetes sprawling evolution ("PetSets", for example) and waiting for API objects to graduate from alpha or beta can seem like waiting for Christmas, the stable APIs are rock solid.

Those who try Kubernetes stable APIs never go back.

Kubernetes Compared to Ubuntu LTS or RHEL

Redhat Enterprise Linux famously has a ten year long-term support guarantee. Their kernel patches and related build process is supposedly so gnarly that no one, besides a small handful of dedicated descendants such as CentOS or OEL, can really claim to have binary compatibility. Ubuntu halves that to five years. CoreOS (used to) throw it all to the wind with "automatic updates" sold with an inspiring plea that updates must be autonomous lest we fail to "secure the internet."

In the case of the major cloud providers and their "Managed Kubernetes Platforms," they take care of control plane upgrades for you. As part of that, Kubernetes platform providers are magically handling the migration around backwards-incompatible or forced migrations within upstream Kubernetes APIs. The Kubernetes-as-a-Service offerings, particularly Google Cloud's Kubernetes Engine (GKE), are the well-polished bellwethers of what is currently the most stable and production-worthy version of Kubernetes.

Kubernetes Community Support Patterns

The aforementioned release versioning design proposal states that users are expected to stay "reasonably up-to-date with versions of Kubernetes they use in production." The other key takeaway is that the upstream Kubernetes community only aims to support up to three "minor" Kubernetes version at a time. In practice, within 1.X where the X is really dang significant, the three-minor policy means Kubernetes 1.5 falls out of scope for SIG-release once 1.8 makes it out the door. That means that if you deployed a Kubernetes 1.6 cluster soon after it came out last March, you were expected to upgrade to 1.7 within roughly nine months or by the time 1.9 shipped in mid-December.

You sow the cluster in early spring and you harvest it before deep winter sets in.

Does Kubernetes release cadence and the short upstream support window hurt the project? Honestly, from the perspectives of end-users, not very much. If you dig through SIG meeting notes, Github issues, design proposals and mailing lists you'll discover that the community's consensus on long-term support is still very much in flux. And, perhaps rightfully so, there's a strong bent toward keeping the upstream project as flexible as possible for as long as possible. When your already released core API primitives are mostly staying the same or rarely have backwards-incompatible changes once out of "beta," why put artificial constraints on "vanilla" Kubernetes releases?

In practice and actual fact, what really matters for older Kubernetes version support is the continued availability and exercising of its end-to-end testing pipeline. If the machinery to quickly update an old release continues to exist, and exist in a state of good (non-flakey) repair, cutting a patch release is just a matter of someone -- you, your provider or your vendor -- having the engineering gumption to push it through. If a critical security fix isn't back-ported to an older Kubernetes version, that's a strong sign that no reasonably professional team is using that version in production anymore.

Upgrading a Live Kubernetes Cluster

One of the magical things about orchestrators is that they or their configuration files inevitably become nearly Turing complete. If you have big Kubernetes cluster with diverse workloads, you'll likewise want an SRE with Alan Turing-level Kubernetes smarts at hand to ensure upgrades go smoothly.

Adherents to the idea of self-hosted Kubernetes clusters take the Turing gambit one step further and are hurtling toward the notion that a cluster can manage itself. There are even Kubernetes installer projects that stretch the self-hosted notion deep into inceptionville by running clusters upon clusters upon clusters upon... it's turtles all the way down.

While the basic APIs that Kubernetes reliably supplies are becoming key building blocks of interesting solutions to all types of distributed systems problems, there is healthy skepticism at the notion of "self-driving, self-hosted" clusters.

Even the community endorsed management tools and installers have yet to achieve enterprise-grade, highly-available Kubernetes deployments out of the box. Google Cloud itself runs its GKE Kubernetes-as-a-Service control plane as externally virtualized VMs that live-migrates to avoid component failure (rather than "self-drive" within the cluster control plane).

One viable strategy is to deploy once and leave Kubernetes alone, to cross your fingers that a bug in the underlying operating system or Docker itself doesn't force your hand. For an internal-facing cluster a "deferred maintenance" strategy has been completely valid for many early adopters. Just pray to sweet baby Kubernetes Jesus (Kelsey Hightower) that you never have to leap from Kubernetes v1.3 to v1.9.

Moving Kubernetes Workloads to New Clusters instead of Upgrading

The most reliable strategy for upgrading a cluster is thus a phantom cluster "headswap." If you can't incrementally update a Kubernetes control plane (and its various components), you incrementally drain the load from an old cluster on to a new one using external load routing of some older-fashioned sort. Or even if you do practice incremental in-place updates, one of your key steps to ensuring the reliability of such upgrades is to run old load on new clusters before trying the stepped migration.

Current Best Alternatives to DIY Kubernetes

The absolute safest place to run Kubernetes application is still Google's GKE. They created it and Google's SRE culture wrote the book on successfully running large-scale distributed systems. With GKE and similar Kubernetes "platforms," you can't touch most of the interesting knobs and buttons that control your clusters. You may eventually pay the ridiculous public cloud bandwidth egress tax. So buyer beware, but BUY NOW.

What if you simply need clusters in places where GKE is yet to exist, like on your rpi3?

This is probably the most fascinating area of the Kubernetes community, particularly the vendors. There are now at least two dozen viable Kubernetes distributions. Like carbon-copies of Uber or InstaCart tailor-made to exploit local market quirks, there is a torrent of Kubernetes VARs crafting their pitch just beyond the horizon.

So what do you do after you've outgrown minikube and realize that every pod in your kops cluster has "root" access to your control plane? Find your favorite VAR and demand vanilla Kubernetes, in any form, that's reasonably up-to-date and has a well-proven plan for handling upgrades. Then forget about it and focus on building on its abstractions and the things around it that actually impact your product.

Closing Thoughts on Kubernetes Releases

Kubernetes and the democratization of distributed systems is here to stay. While keeping up with the pace of change is difficult, just imagine the resources you would need to replicate it.

If the SIGs shut down and Google's engineering teams vanish in a puff of an EU regulators anti-monopoly death ray, we'd still use and love Kubernetes v1.X for a very, very long time. The contributor and leadership community is constantly discussing the balance between stabilization and velocity. If you have any doubts, grab a hot beverage and cozy up with Brendan's Burns keynote from the latest Kubecon.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

Conclusion

As always, it's complicated. This is one of the reasons we recommend image-based application deployments, as opposed of using traditional "managed" Kubernetes clusters.

How does it work?

The open-source Gravity project allows developers to package their applications and Kubernetes itself into a single deployable tarball. Think of Gravity as a "Docker for the entire Kubernetes cluster". This way the burden of Kubernetes version management disappears, and this also allows you to move your Kubernetes clusters between environments with ease, or even deploy your applications into someone else's clouds or on-premise and air-gapped environments.

Thanks to Sasha Klizhentas, Kraig Amador and Greg Kogan for reading a draft of this.

Table Of Contents

- What is the Kubernetes Release Cycle?

- There is no such thing as Kubernetes LTS (and that's fantastic)

- Kubernetes founding story and leadership background

- Kubernetes Special Interest Group Background

- Kubernetes Release Versioning Background

- Kubernetes Historic Release Cadence

- Kubernetes Feature Development Process

- Kubernetes Compared to Ubuntu LTS or RHEL

- Kubernetes Community Support Patterns

- Upgrading a Live Kubernetes Cluster

- Moving Kubernetes Workloads to New Clusters instead of Upgrading

- Current Best Alternatives to DIY Kubernetes

- Closing Thoughts on Kubernetes Releases

- Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

- Conclusion

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Tags

Subscribe to our newsletter