Table Of Contents

Teleport Blog - In Search of a Perfect Access Control System - Mar 4, 2021

In Search of a Perfect Access Control System

Evergreen Challenge

Every cloud has its own identity and access management system. AWS and Google use a bunch of JSON files specifying various rules. Open source projects like Kubernetes support three concurrent access control models - attribute-based, role-based and a webhook access control, all expressed using YAML. Some teams are going as far as inventing their own programming language to solve this evergreen problem.

As many engineers before us, we faced the challenge of choosing the design and the tooling from the kaleidoscope of JSON, YAML and custom languages for our own software's access controls. Which system is the best, and can there be one language to rule them all? What are the properties of a good access control system, and what mistakes of the past should we avoid?

Time Sharing and First Pen-testers

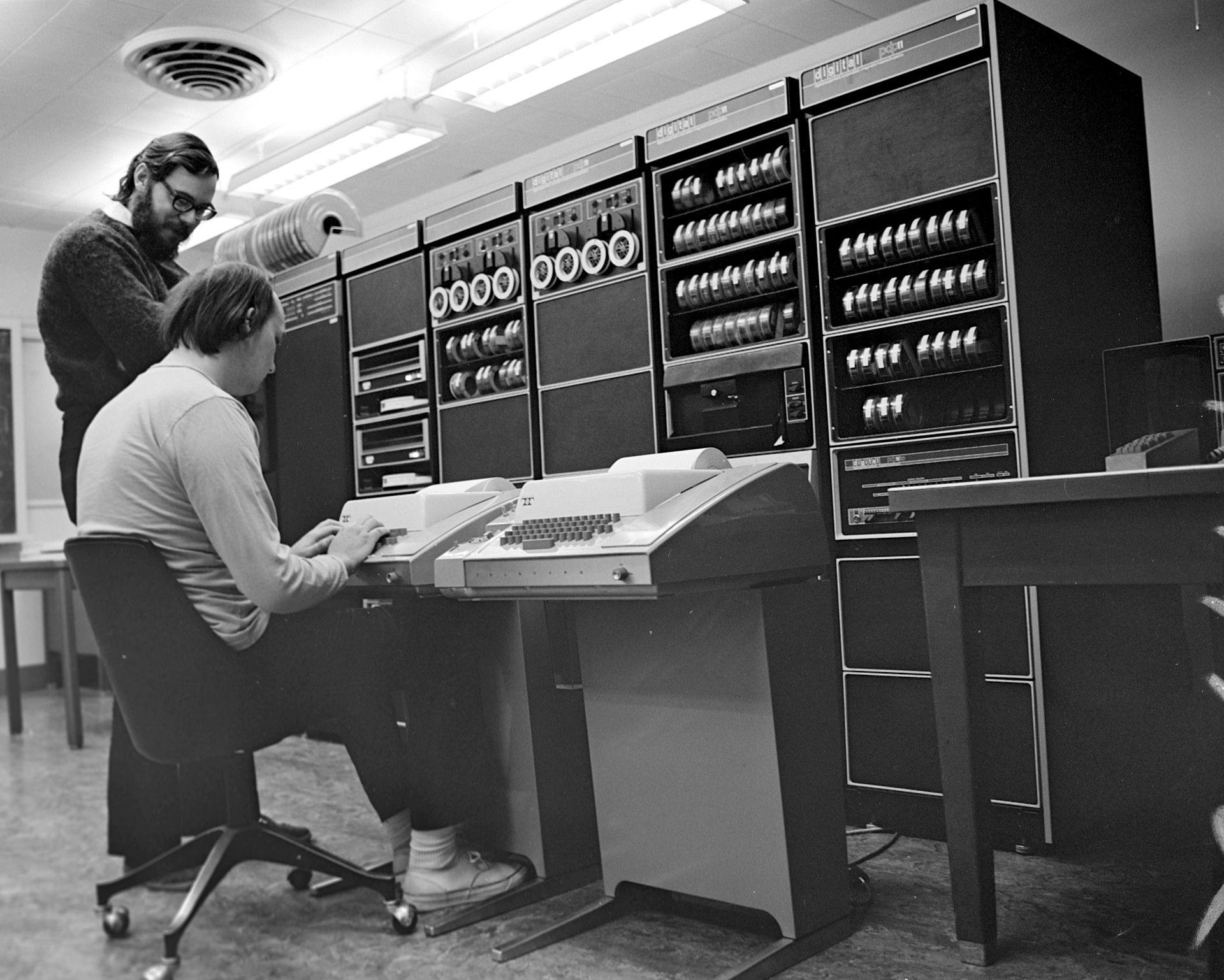

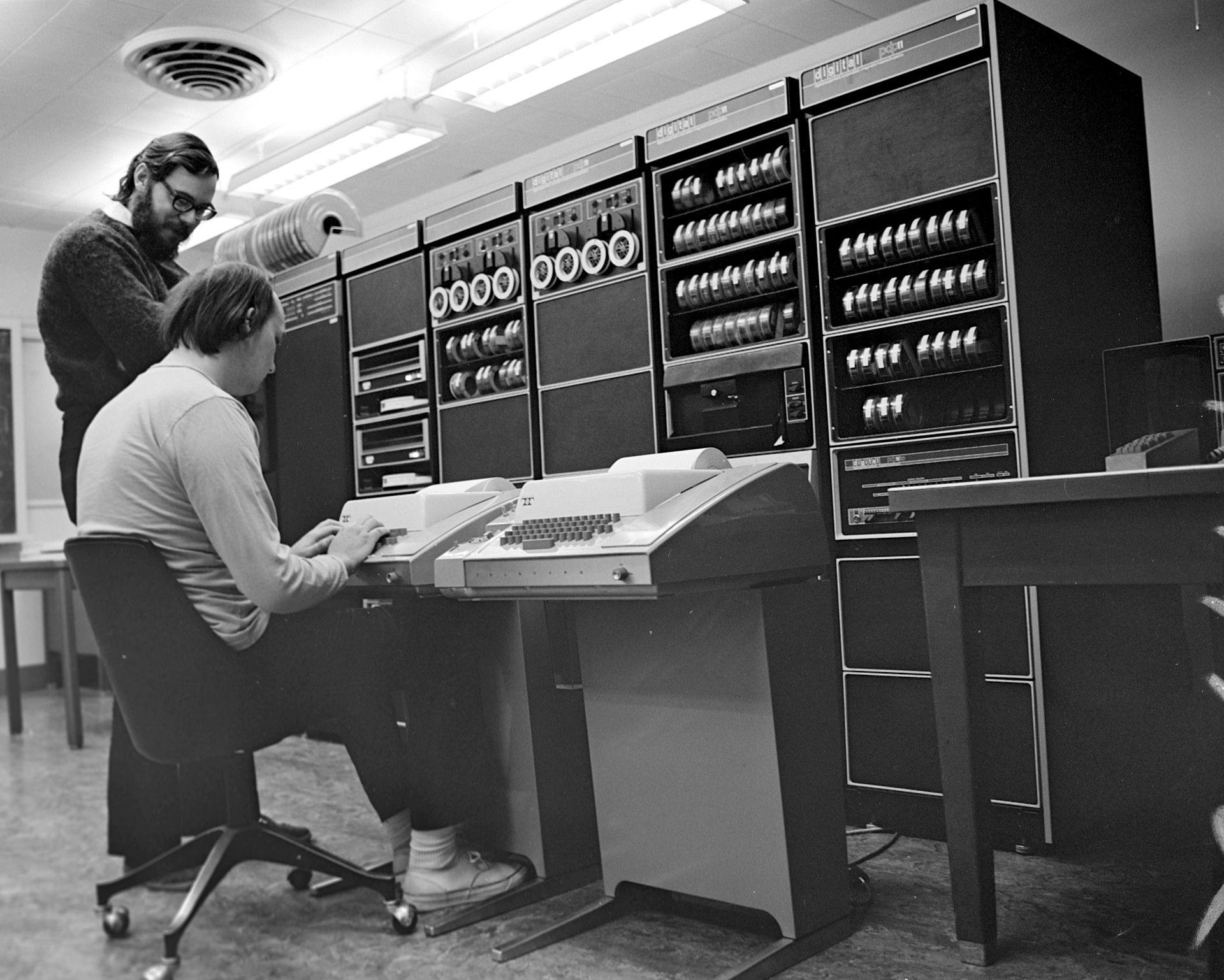

In the early 1960s one computer could be accessed by one person, program and team at a time. Computers were quite expensive; a PDP-1, for example, would cost you a whopping $120,000. That's close to $1M adjusted for inflation in 2021.

You could securely use the computer for different applications as long as the files and data for different projects were kept separate. That was a serious bottleneck, and by the mid-sixties manufacturers offered time-sharing systems that allowed many folks to use computers at the same time.

The arrival of time sharing made folks at the U.S. Air Force worried. There could be two programs residing in the storage and sharing compute and memory at the same time. What if a program working on a lower privilege level hacked the system and gained access to sensitive data of another program?

To assess the scope of the problem, USAF formed a special task force to figure out the impact of such hacks and come up with a solution. The team came back with some bad news: operating systems at the time were not designed at all to protect from a malicious program. The executable had almost unrestricted capability to reference any main and auxiliary memory locations. The task force concluded that a new approach was needed [1]:

The operating systems were not designed to be secure, provide a malicious user with any number of opportunities to subvert the operating system itself.

...

A system designed to be secure, containing;

A) An adequate system access control mechanism

B) An authorization mechanism

...

Bell-La Padula Security Model

In 1972, two computer scientists were assigned with the task of designing such a system [2].

In the summer of 1972, The MITRE Corporation initiated its task to produce a report titled “Secure Computer Systems.” The modeling task fell to Len La Padula and me. David E Bell.

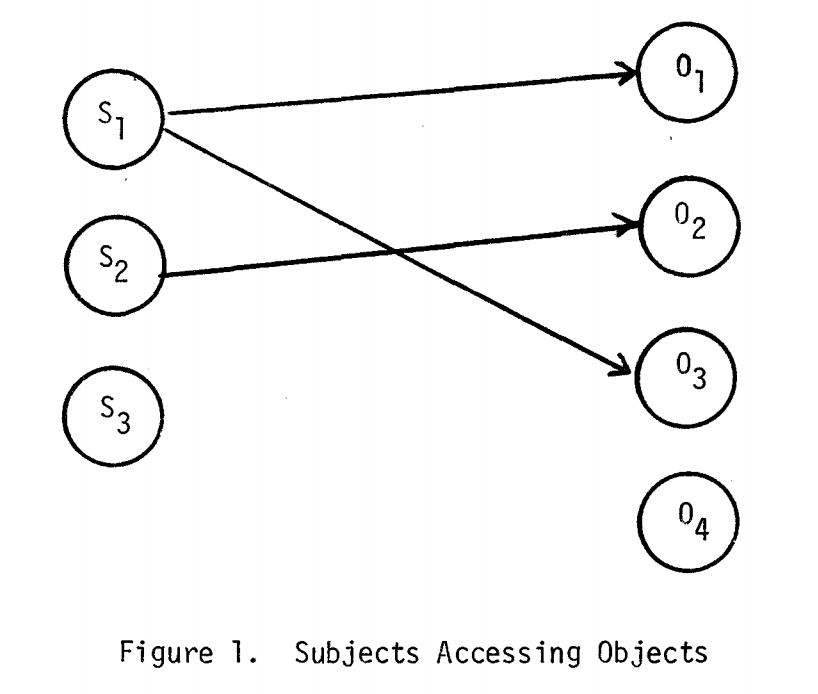

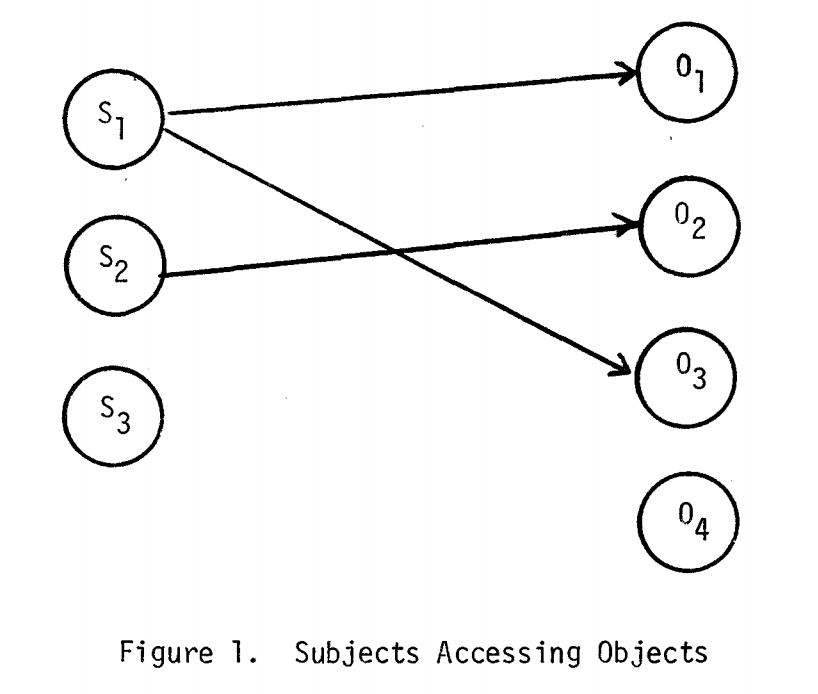

In 1972-1974 David E. Bell and Leonard J. La Padula came up with the theoretical foundations of access control systems [3] and then worked with programmers to implement that in the most promising O.S. at the time — Multics [4]. In the Multics paper, they defined elements of both models still used to this day — subjects, objects and access control lists.

subjectsare actors, like processes and programs in execution.objectsare passive things, like data, files, programs, subjects.

Subjects can access objects. These access modes are governed by access attributes:

e- no access,r- read-only,a- can write, but not read,w- can read and write.

They defined access of subject to object with a triple:

(subject, object, attribute)

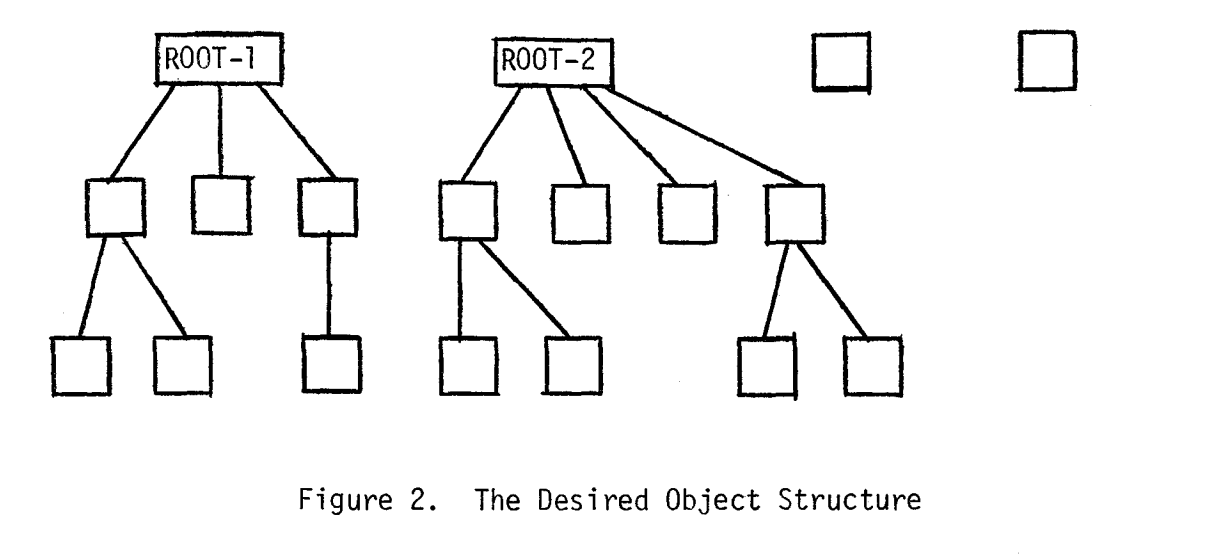

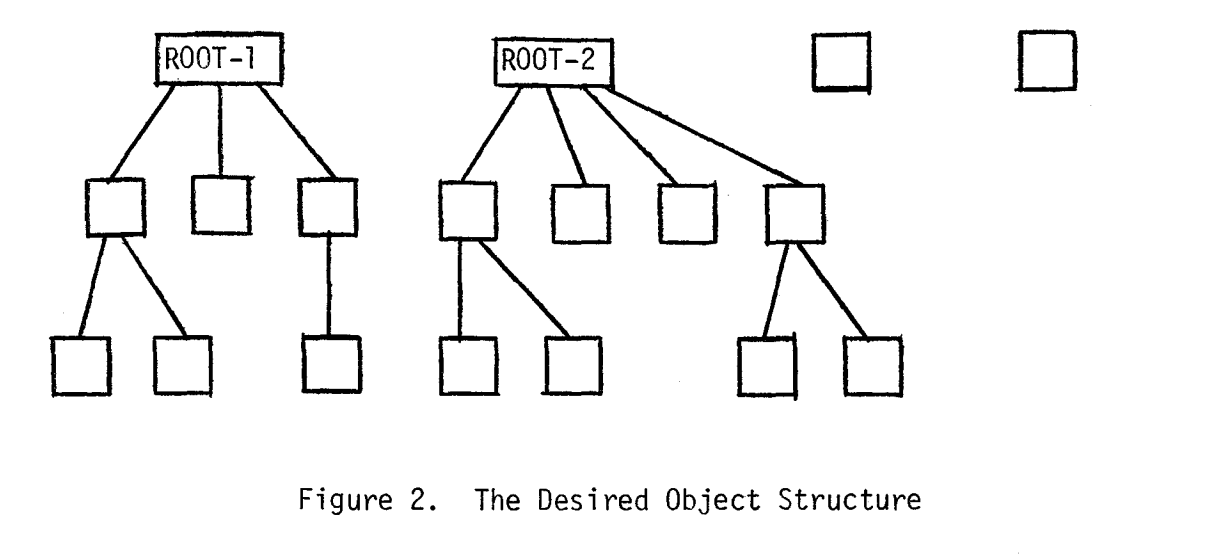

Objects are organized in a tree-like structure, forming a hierarchy.

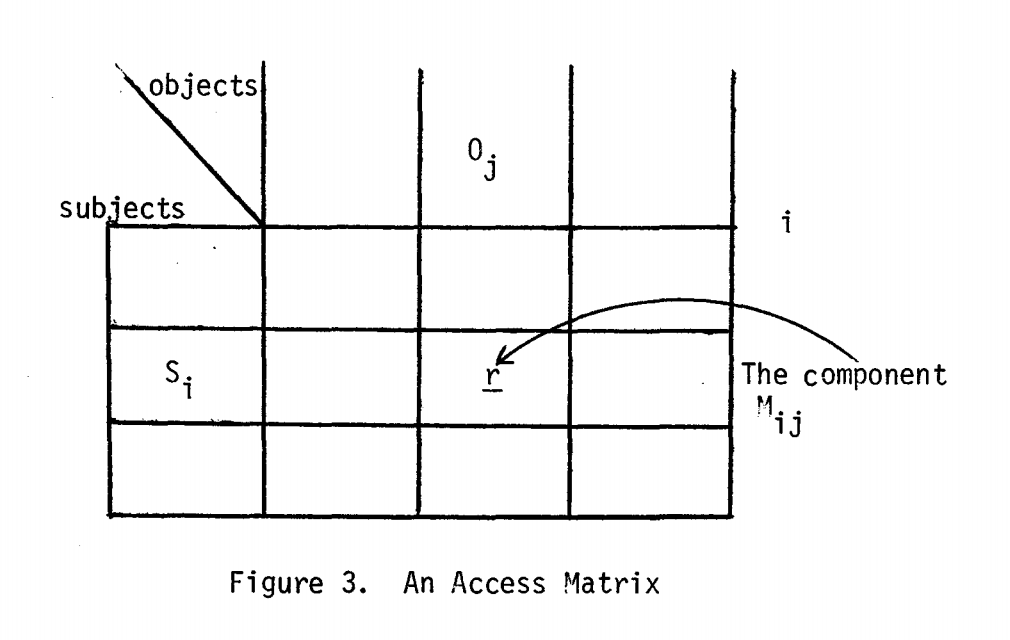

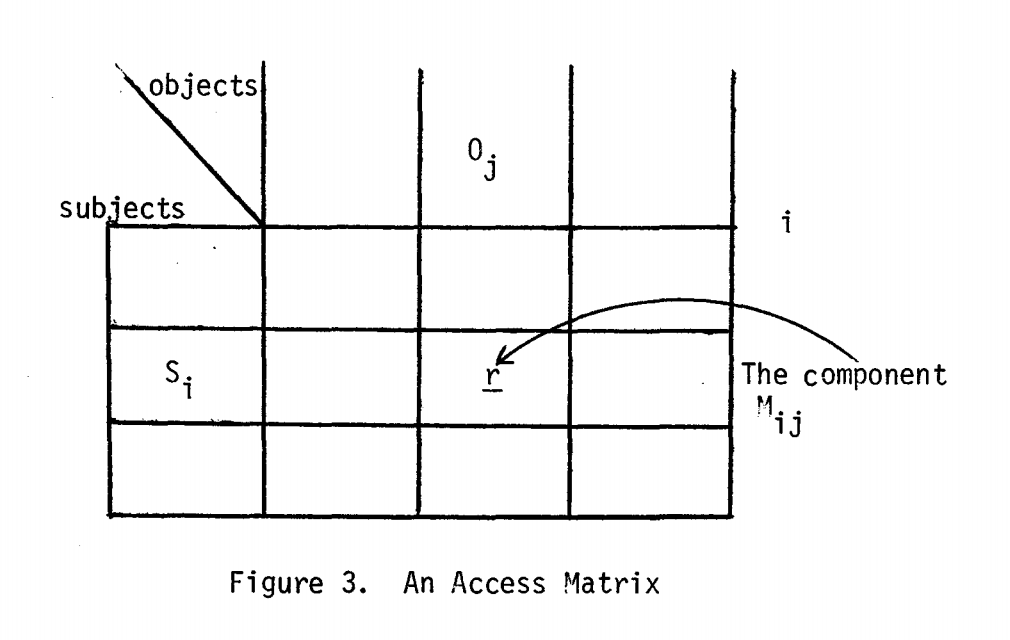

An access matrix specifies access modes (e, r, a, w) in which subjects can access objects.

Because MITRE corporation's research was funded by the military, you would find a couple of parts unfamiliar to most Unix users — category and classification levels for the U.S. Military — "unclassified", "confidential", "secret", "top secret". Categories are general topics such as "Nuclear", "NATO" or "Crypto".

Security level assigned to an individual and object is a pair:

(classification, set of categories)

A user can access a document if their security level "dominates" the document level:

(class 1, category-set 1) dominates (class 2, category-set 2) if and only if

class 1>= class 2 and category-set 1 includes category-set 2 as a subset

Simple Security Property

The researchers have defined a first property, as a simple security property:

For a triplet (subject, object, read) the security level of a subject always "dominates" security level of an object.

In other words, subjects can only read objects with the same or lower security level.

This property is also sometimes called "Read down" or "ss-property".

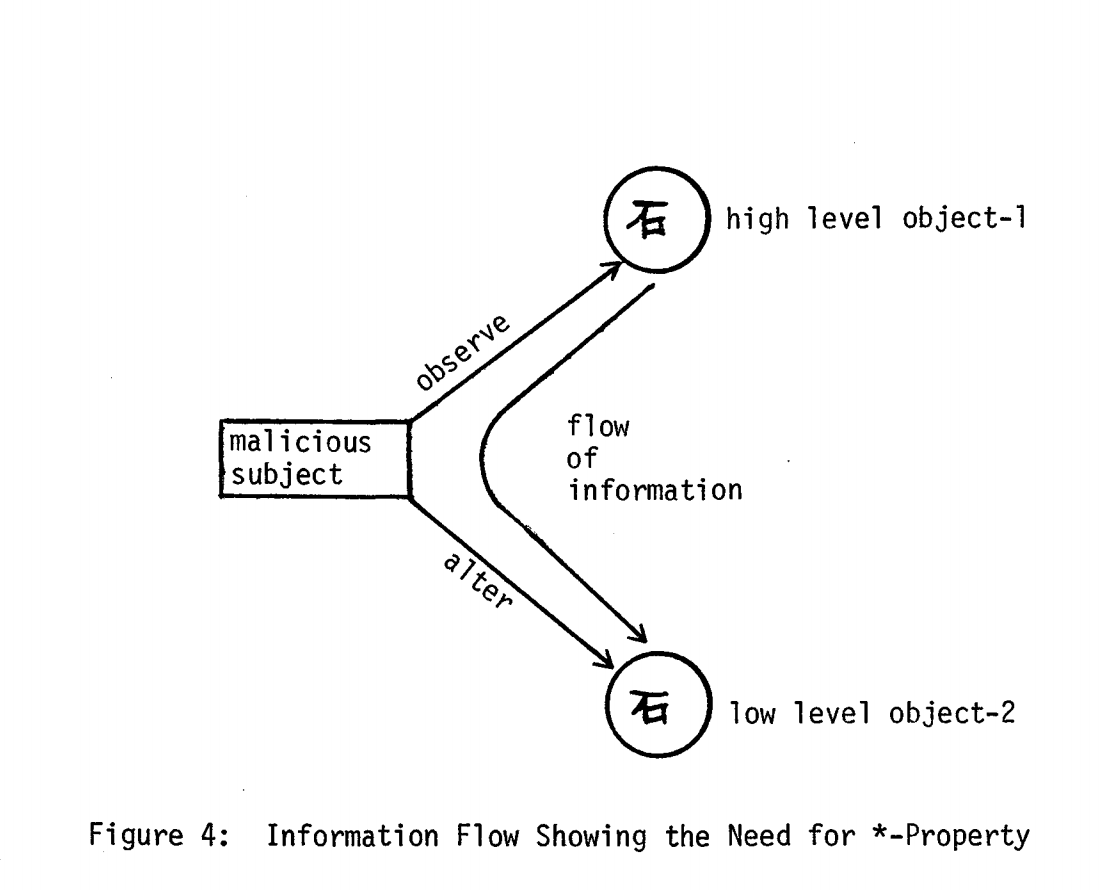

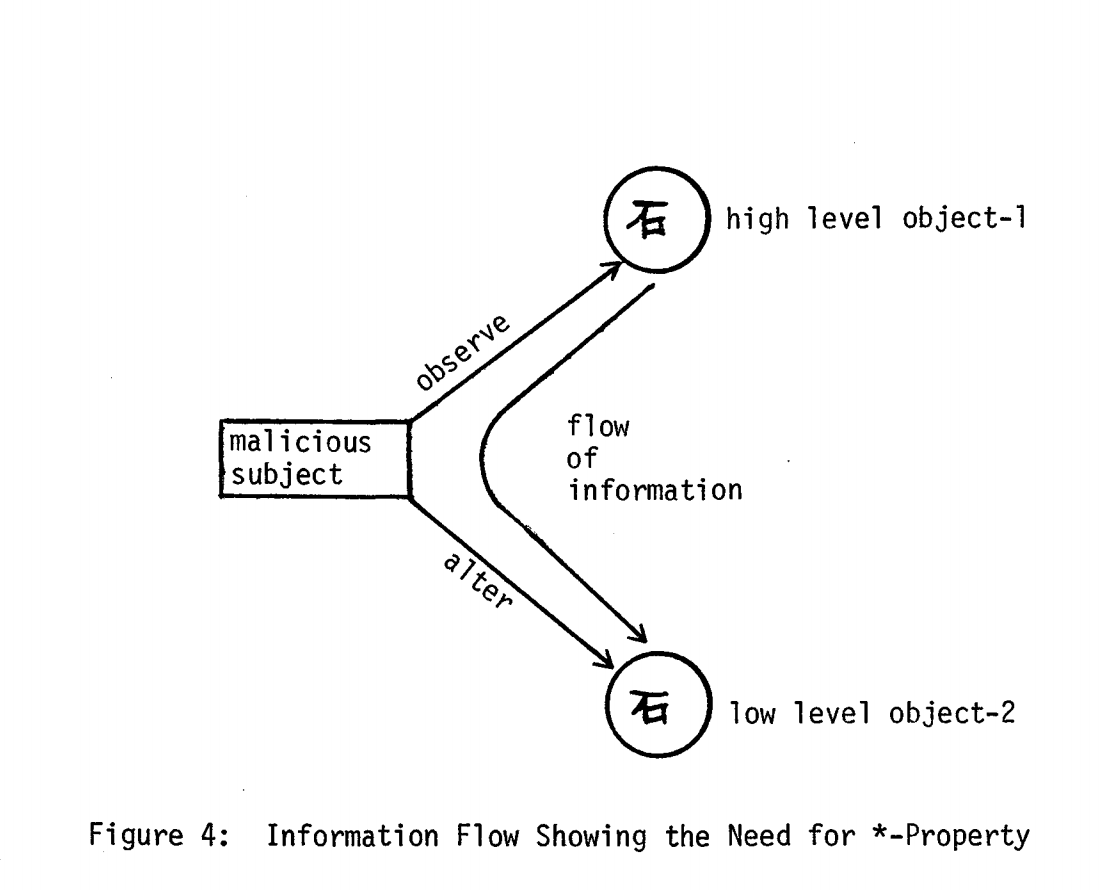

Star Property

Bell and La Padula noticed that "simple security property" is not enough to protect classified information. A malicious program could pass classified information along by reading the classified docs on one level and writing on lower level:

They called it "*-property":

in any state, if a subject has simultaneous "observe" access to object-1 and "alter" access to object-2, then level (object-1) is dominated by level (object-2)

In other words, you cannot read objects at higher security level and write to objects at lower security level. Some folks call this property "Write Up". With this rule in place, any system drifts towards higher and higher clearance level documents and it creates a practical problem — what if you still need to communicate the level "down"? They defined "trusted subjects", exceptions to the "*-property" rule to communicate some information down and lower clearance of the documents.

Discretionary and Mandatory

To conform to military regulations, the researchers defined a "mandatory" or "non-discretionary" security policy — an individual may not exercise their judgment to violate access standard, and the enforcement is mandatory.

Two systems have emerged: Mandatory Access Controls (MAC), in which individuals have no say in whether to set up their access levels, and Discretionary Access Control (DAC), in which folks have some say who can access what.

Discretionary security is defined by access matrix above and specified as "ds-property":

if (subject-i, object-j, attribute-x) is a current access ... then attribute-x is recorded in the (subject-i, object-j) component of M ...

In other words, subjects can access objects if there is a matching access attribute in the matrix.

Basic Security Theorem

Bell and La Padula defined "Basic security theorem" as a combination of "ss-property", "*-property" and "ds-property'.

In their assessment, the system is secure if:

- Users can only read resources at lower or equal security levels (Read Down)

- Subjects cannot read objects at higher level and write to objects at lower level (Write Up)

- System enforces access attributes on any subject-object access.

The researchers were excited about "inductive nature" of the Basic Security Theorem — the system will stay secure through all transitions as long as these three rules are enforced.

In the security world, this is also called security invariant — a property that system keeps true at all times despite all the changes.

Multics

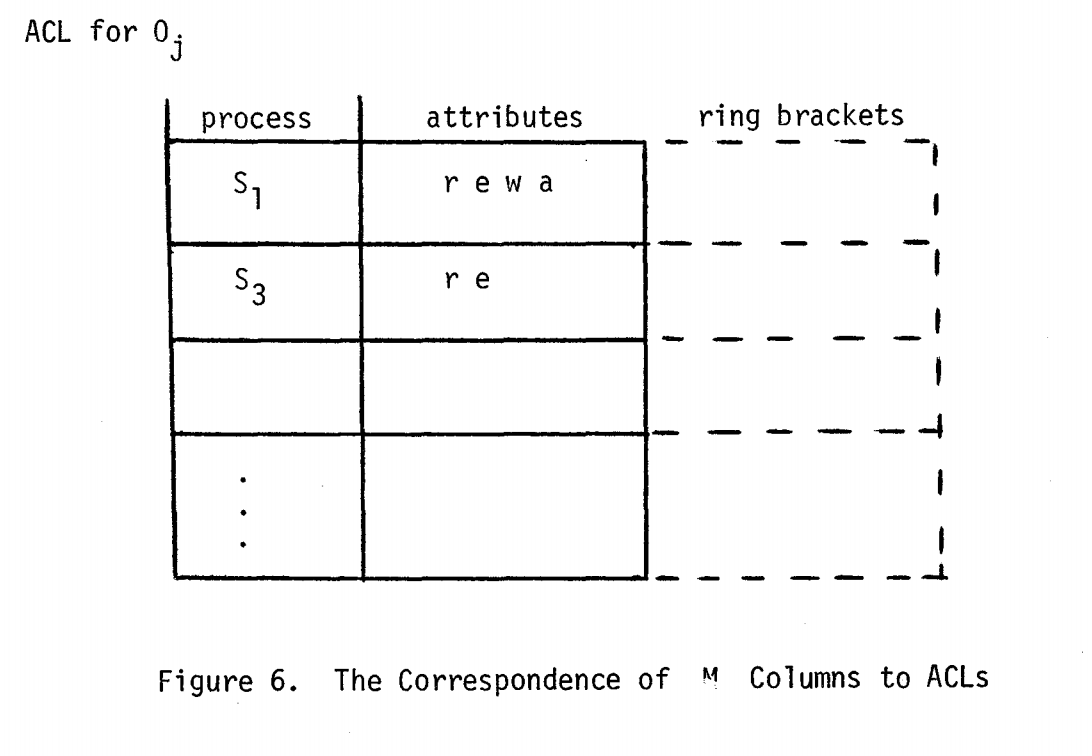

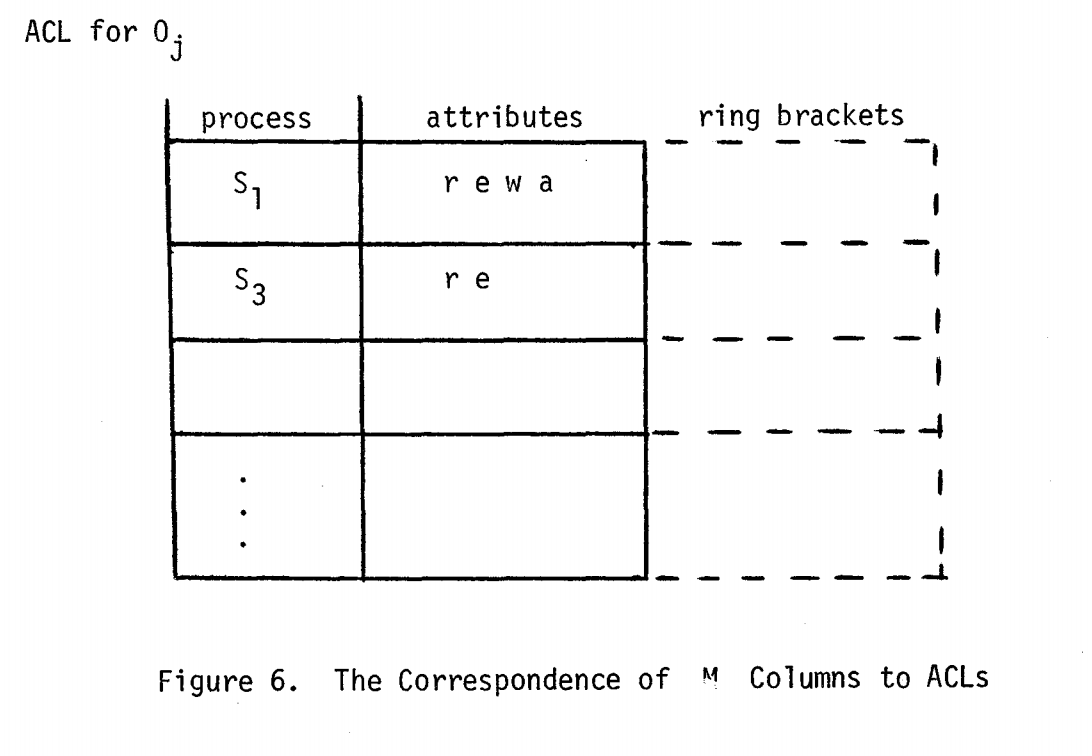

Based on this paper, Multics engineers introduced access control lists — ACL.

Multics "ACLs" were composed of (process, ring bracket) pairs, where process is analogue of

the paper's subject and ring bracket is a clearance level.

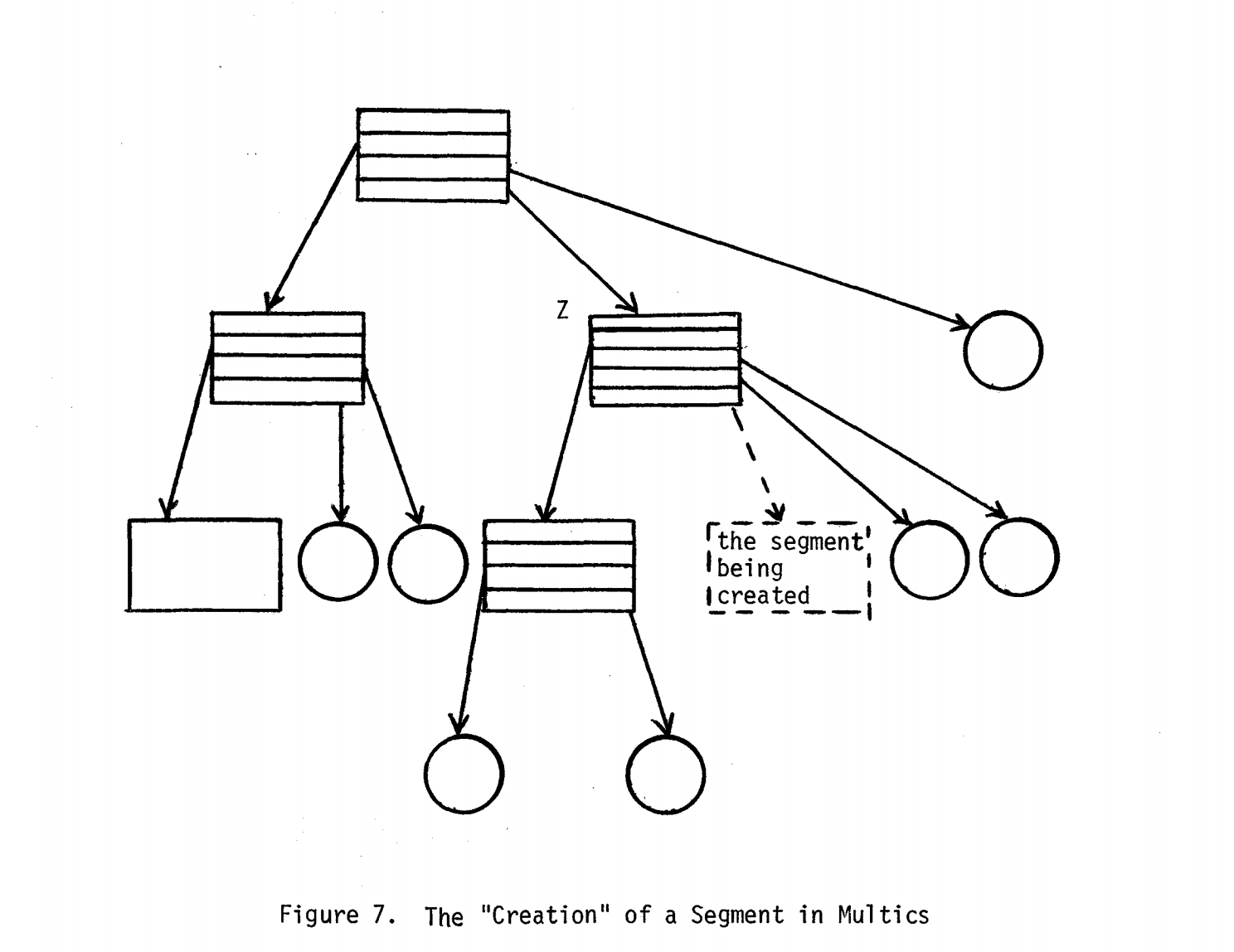

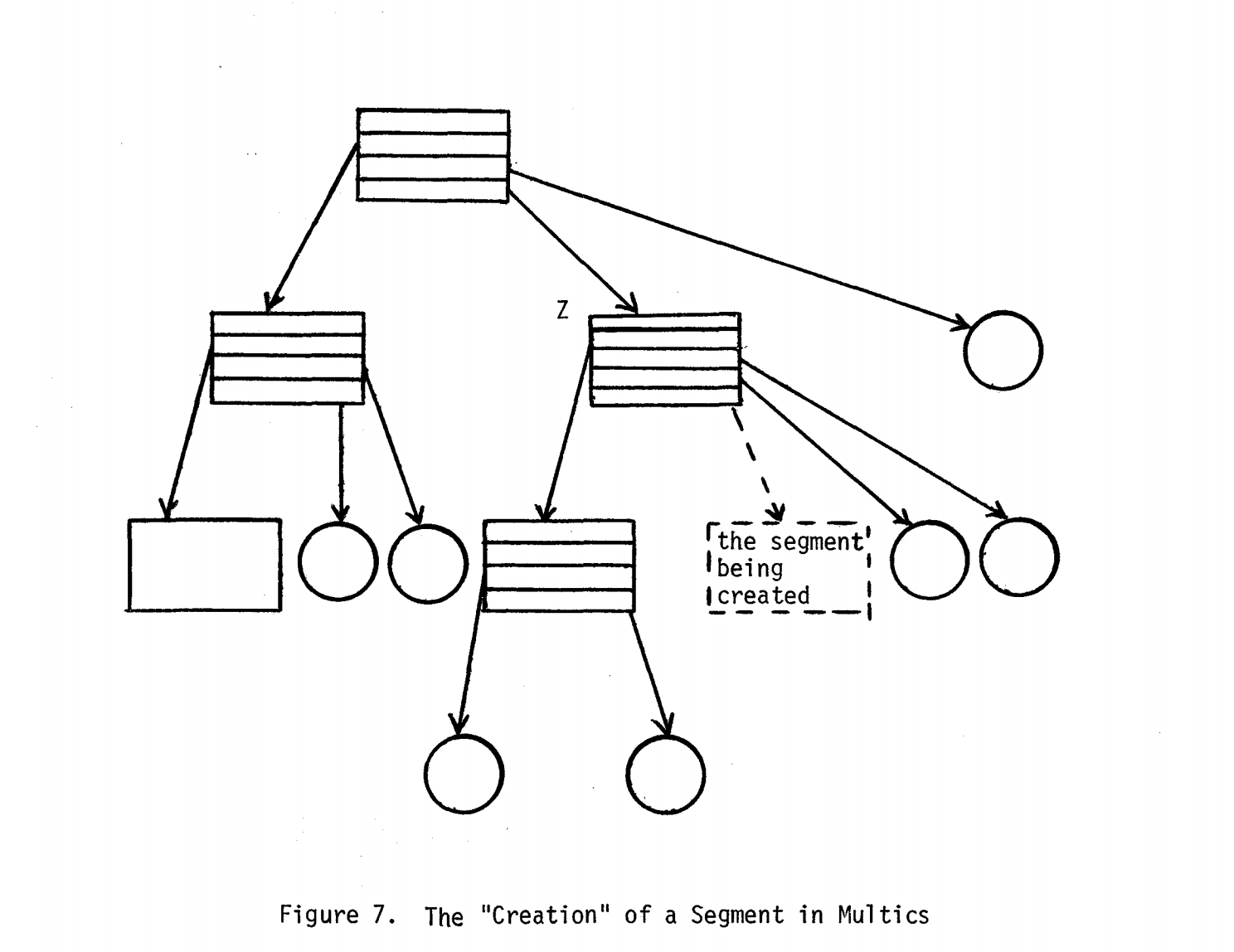

Objects could be "directory segments", data segments, certain I/O devices, certain address spaces and sockets.

Multics stored ACLs in the parent directory of an object and manipulated them by altering the directory properties. Control over an object was represented by write permission on an object's directory.

A request to give access to an object is allowed only if the requesting subject

has current w access to the parent of the object.

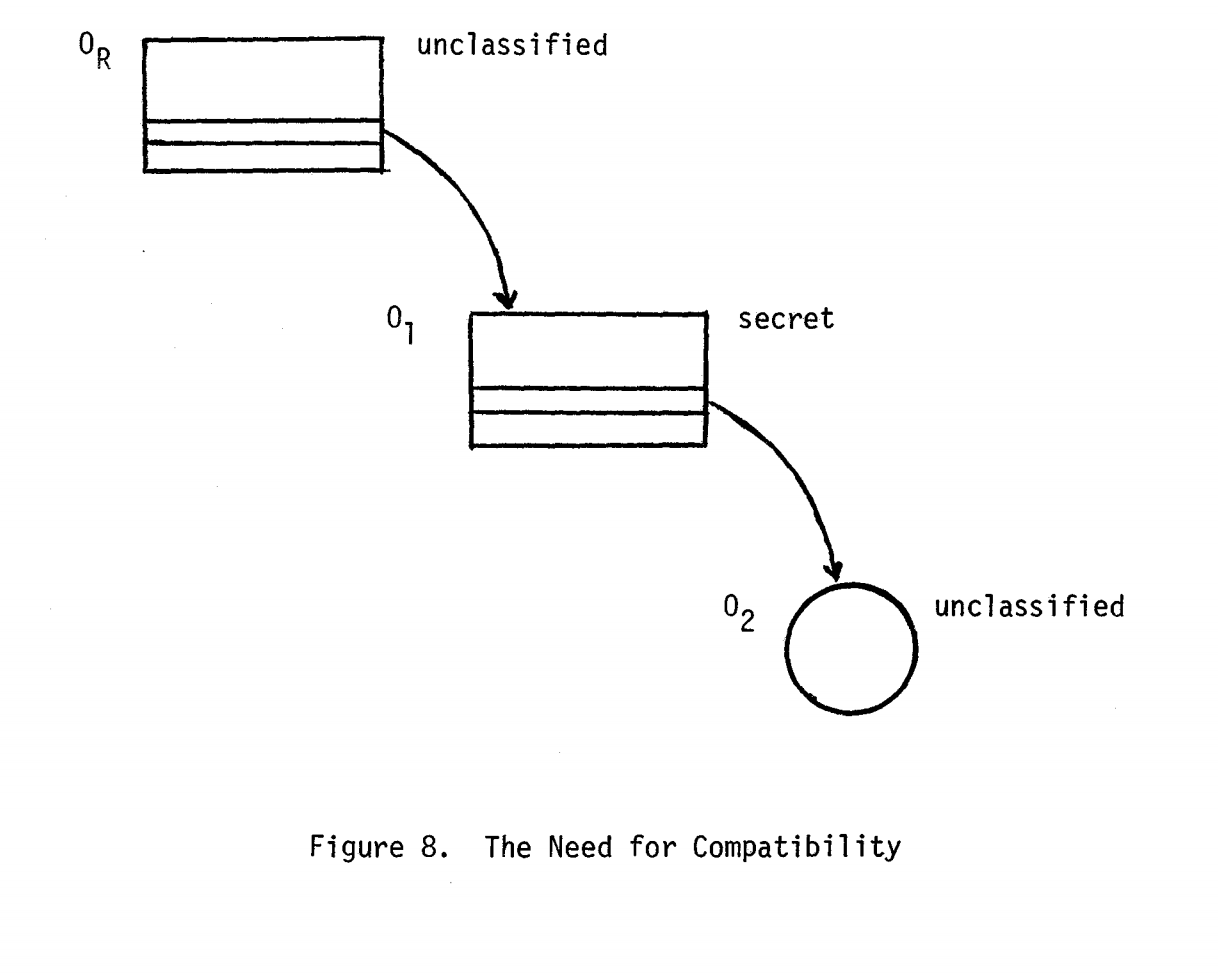

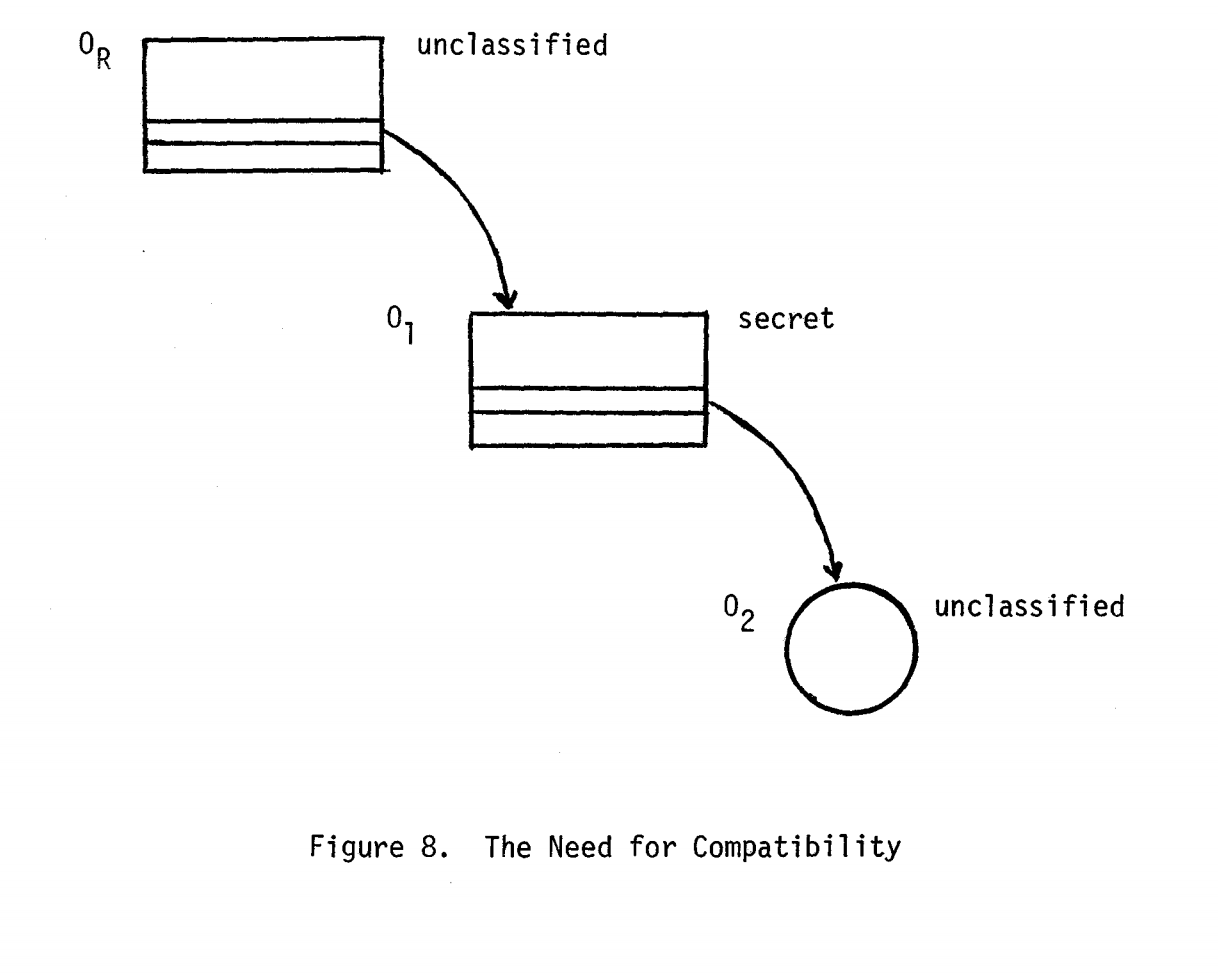

Imagine a situation when a user created unclassified folder Or, then in it,

created a secret folder O1 and placed unclassified file O2 in it.

An unclassified user can't access the file O2 because they can't access the secret folder O1.

This would have violated the ss-property — because unclassified users can't read the

secret data and *-property, where users can't read secret data and write to non-secret files

at the same time. They called it "The need for compatibility" — a child's object

security levels should be higher than the parent's object security levels.

Modern-Day Descendants of Bell-La-Padula Model

Chances are, you are using discretionary access control implementation of the Bell-La-Padula model every time you access a file on your system.

Discretionary Access Controls

Unix devs were frustrated with Multics' complexity. Even Unix itself is a pun on Multics — "Uniplex information and computing service", compared to Multics' "Multiplex information and computer services". They dropped most of the complex stuff and kept only the discretionary part securing access to files with permissions.

DAC defines an owner of a resource, for example a file. A file owner specifies what others

can do to this file. Linux access control list system defines a set of permissions - read (r), write (w) and execute (x).

Users are divided into three classes: owners, groups and other. Every Linux file has a list of

access controls defined for every user class. Here is, for example an ACL for a file "animals.pl" on my computer:

$ ls -l animals.pl

-rw-r--r-- 1 sasha admins 187 Nov 28 15:14 animals.pl

This ACL says that user sasha is allowed to read and write the file,

and any member of group admins can only read the file.

Mandatory Access Controls

Unix gained more popularity and became the de-facto operating system, spawning Linux. However, the military still needed their access levels and clearances.

Let's recall that in DAC system you can create a file, and as an owner, you can also define permissions for it. In MAC system, the owner is not relevant and the system access controls are mandatory; therefore, users cannot override their security clearance level.

NSA folks have built SELinux to define missing mandatory access controls. SELinux's checks kick in after file-system's access controls are applied.

In DAC system, a user can make a mistake and allow anyone to read

files in ~/.ssh folder. With SELinux enforcing mode, Linux will deny anyone access

to the ~/.ssh folder, regardless of file permission, unless explicitly allowed by a policy.

Here is a Centos's SELinux example showing that SELinux attaches attributes to files — a security context:

$ ls -Z /var/www/html/index.html

-rw-r--r-- username username system_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t /var/www/html/index.html

An Apache server is running in a SELinux domain httpd_t:

$ ps axZ | grep httpd

system_u:system_r:httpd_t 3234 ? Ss 0:00 /usr/sbin/httpd

The server won't be able to access file /home/username/myfile.txt, even though it's world-readable,

because its security context does not match the domain.

$ ls -Z /home/username/myfile.txt

-rw-r--r-- username username user_u:object_r:user_home_t /home/username/myfile.txt

Critique and Consequences of Bell-La Padula Model

Because David E. Bell and Leonard J. La Padula's research was funded by the military,

they were mostly concerned with levels of clearance and leaking data.

Their research did not cover data integrity, encryption, distributed systems and other aspects of security.

In its first iteration, they had to surrender *-property by introducing "trusted users", or basically super admins.

They did not define how exactly those trusted users were granted and revoked privileges.

The theoretical foundations of the "Basic security theorem" were not as sound as researchers assumed

them to be. For example John McLean, a researcher noted [5] that if you replaced *-property with its

complete opposite +-property, where subjects can only "write down", the parts of the theorem would have

still held. Therefore, he concluded, if you defined a similar theorem with one part that is absolute opposite

and the theorem made sense, the definition of security coming from it was weak.

John's doc itself, however, was marked "unclassified" and followed the model John was critiquing precisely.

Jokes aside, I think that John had a point — the theorem was interesting, but not overly practical. Both Multics and SELinux devs had a hard time implementing it in practice, resulting in a quite complex system in Multics and later in SELinux.

Despite this critique, Bell and La Padula came up with an elegant system and created one of the first specs of a security invariant — a property that holds true through all changes if the rules are followed. Their research influenced Linux and many other software systems and introduced ACLs to the world.

90s: RBAC, ABAC and Logic Computing

Fast-forward twenty years and IBM PC architecture reigned over the software market. However, it's not IBM PC vs Apple wars that defined the decade, but the Web and rise of distributed systems. Discretionary access controls designed in the 1970s were not sufficient any more to solve distributed access problems or satisfy large organizations' needs.

Civilians Strike Back with RBAC

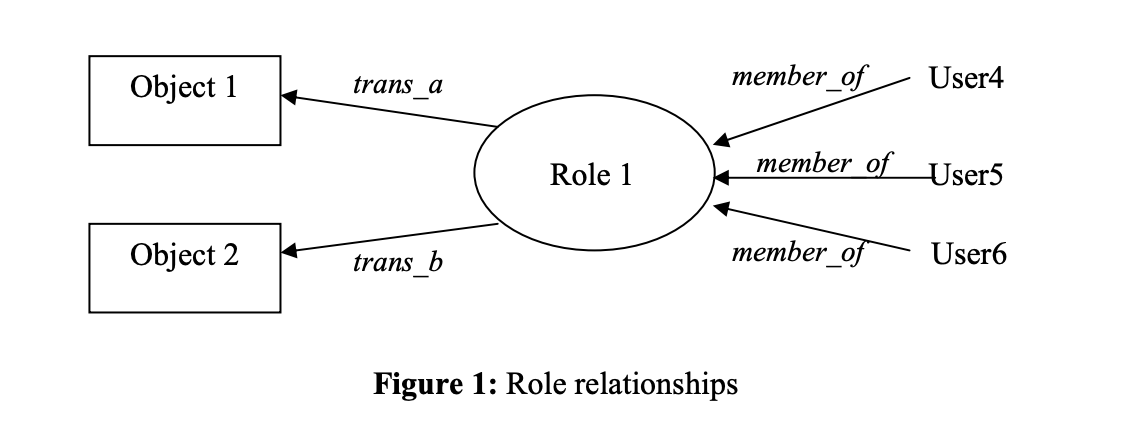

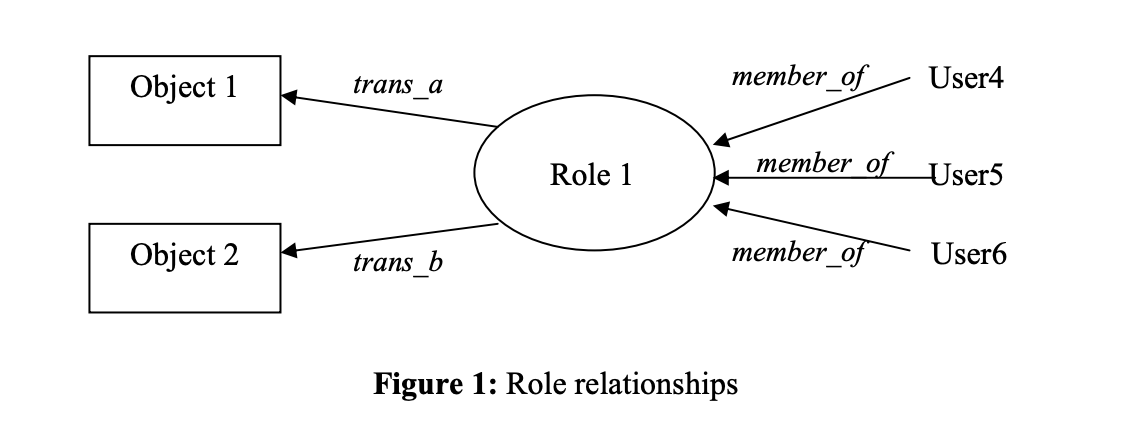

Folks at the U.S. Department of Commerce have noticed that both DAC and MAC alternated between assigning security privileges to files or users. [6] Quite often in large organizations, users did not own the files they were working on.

Engineers David F. Ferraiolo and D. Richard Kuhn looked at the real world for inspiration:

For example, the roles an individual associated with a hospital can assume include doctor, nurse, clinician, and pharmacist. Roles in a bank include teller, loan officer, and accountant.

They have decoupled permissions from users or objects, and assigned them to abstract roles. In their definition, a transaction was any operation to access or modify the data, and roles grouped transactions together:

Ferraiolo and Kuhn's inspiration came from the database world. They were excited to set up many-to-many relationships between clients and permissions.

Subjects, like clients or users were performing transactions, like operations on a file:

# For each subject, the active role is the one that the subject is currently using:

AR(s: subject) = {the active role for subject s}.

# Each subject may be authorized to perform one or more roles:

RA(s: subject) = {authorized roles for subject s}.

# Each role may be authorized to perform one or more transactions:

TA(r: role) = {transactions authorized for role r}.

# The predicate exec(s,t) is true if subject s can execute

# transaction t at the current time, otherwise it is false:

exec(s: subject, t: tran) = true if subject s can execute transaction t.

Each subject could hold many roles. To figure out if a subject could commit a transaction, the algorithm had to enumerate all active roles of the subject and figure out if the role could perform a transaction. In any organization, roles were not changing that frequently, and admins could keep up with assigning users to roles manually.

This model was so successful that modern projects like Kubernetes use it 30 years later.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

namespace: default

name: pod-reader

rules:

- apiGroups: [""] # "" indicates the core API group

resources: ["pods"]

verbs: ["get", "watch", "list"]

Kubernetes RBAC

Policies as Code: Attribute-Based Access Controls

What if you want to grant access to an employee only during working hours, or based on whether the employee is in the building?

It's hard to say who came up with Attribute-Based Access Controls. And again, folks from the Department of Commerce defined it best in the NIST paper in 2018 [7].

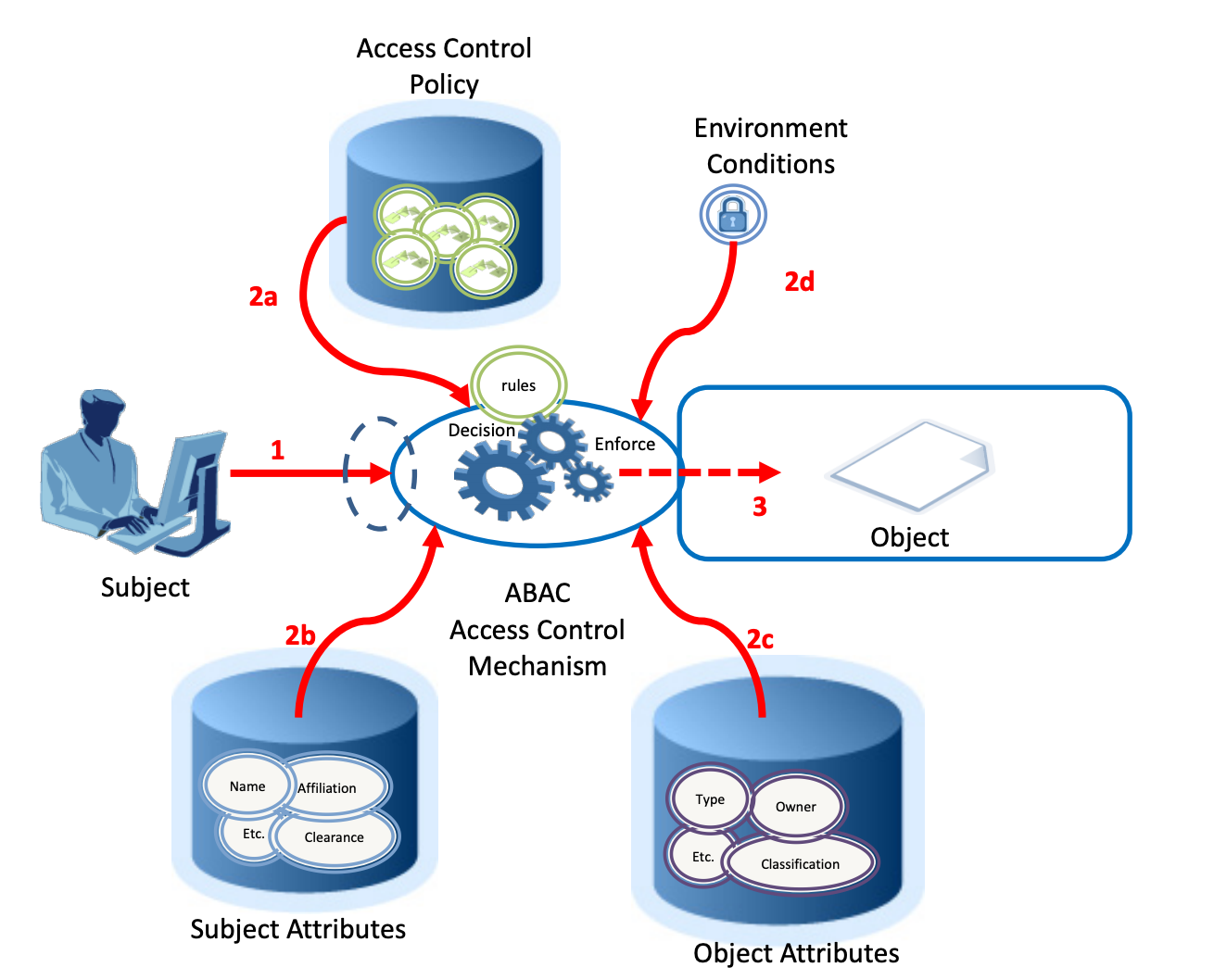

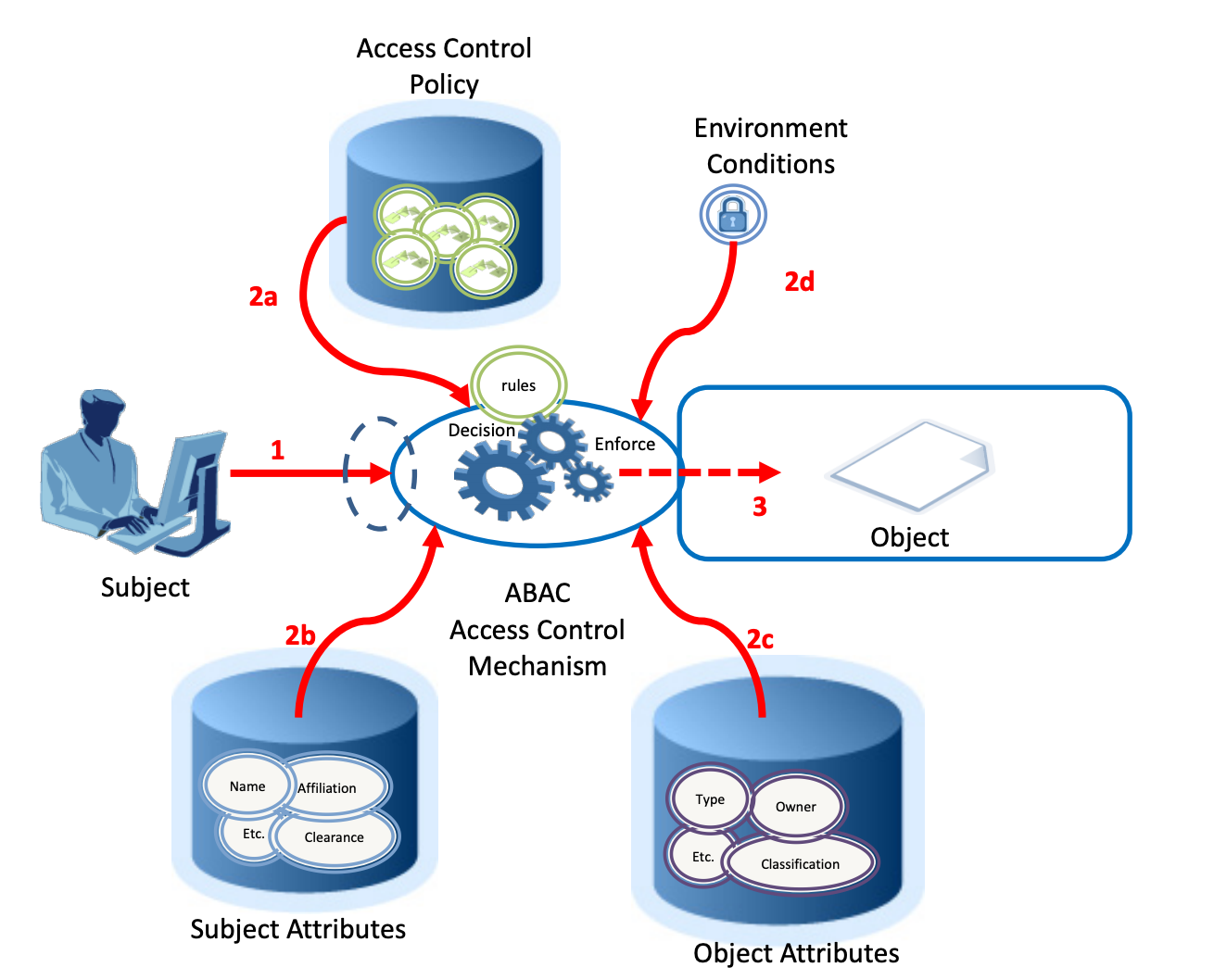

- Subject requests access to object 2. Access control mechanism evaluates a. Rules, b. Subject attributes, c. Object attributes, and d. Environment conditions to compute a decision 3. Subject is given access to object if authorized

So, if a client requested an access, a specialized program would have kicked in. It would have evaluated a set of rules based on object and subject attributes, considered external factors like time of day and location — and voila — the access decision would have been evaluated.

package kubernetes.admission

deny[msg] {

input.request.kind.kind == "Pod"

image := input.request.object.spec.containers[_].image

not startswith(image, "hooli.com/")

msg := sprintf("image '%v' comes from untrusted registry", [image])

}

Open Policy Agent's Language

ABAC is sometimes also referred to as policy-based access controls. Its innovation was to treat policies as special programs.

With ABAC, modern day devs can deploy and distribute policies in the organization using familiar CI/CD pipelines. ABAC went even further than RBAC and decoupled policies from the software or users.

ABAC's flexibility comes at a steep price — a rogue rule or an honest mistake could grant extra privileges. In "legacy" access control systems, you had a chance of formal verification of whether a user had access to a file.

And let's not forget the USAF task force's concern about programs having too many privileges. Because of their flexibility and power, modern policy engines suffer from this exact design flaw too.

Back to the Future: Logic-Based Access Controls

If policy engines are the answer, which policy engine or language is the best? To try and find the answer, let's go back to 1970s France.

At that time, European AI researchers and mathematicians were looking for a new language that would solve a problem of theorem proving and create expert systems.

French mathematician Alain Colmerauer in collaboration with U.K. researcher Robert Kowalski came up with an elegant logic programming language, Prolog.

In Prolog, you declare a set of facts and rules that become a database.

/*Crookshanks is a cat*/

cat(crookshanks).

/*Any cat is an animal*/

animal(X) :- cat(X).

/*What things are animals?*/

?- animal(X).

X = crookshanks

With an access control system designed in Prolog, you could not only say that the access is denied, but could prove that there is no condition under which access would have been allowed.

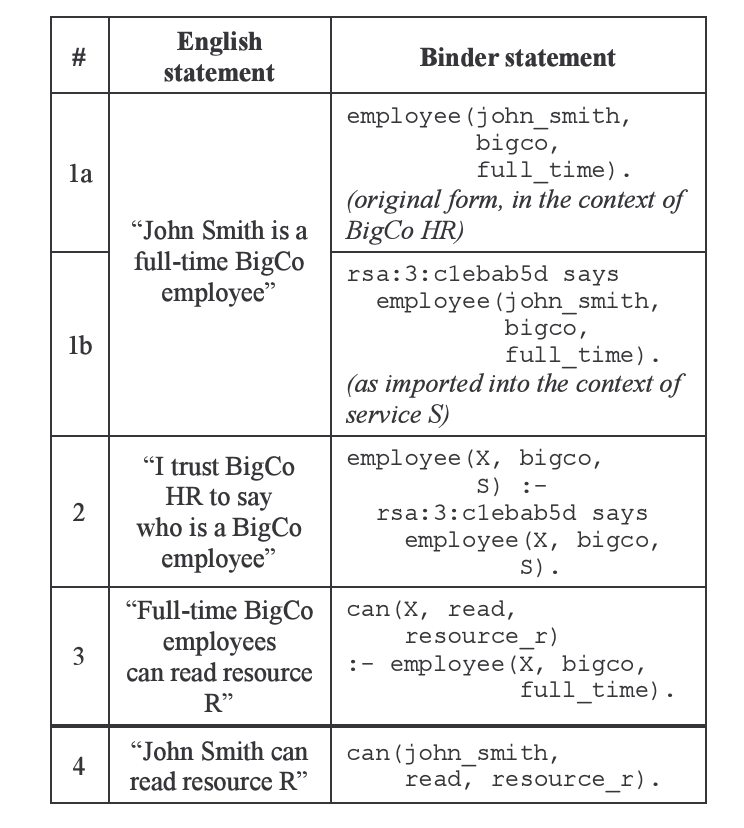

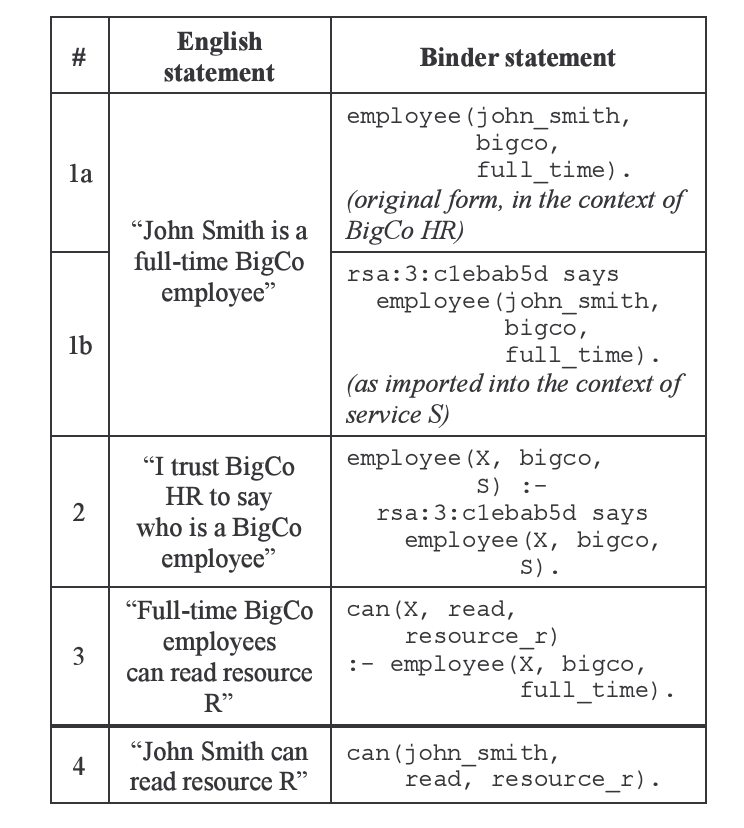

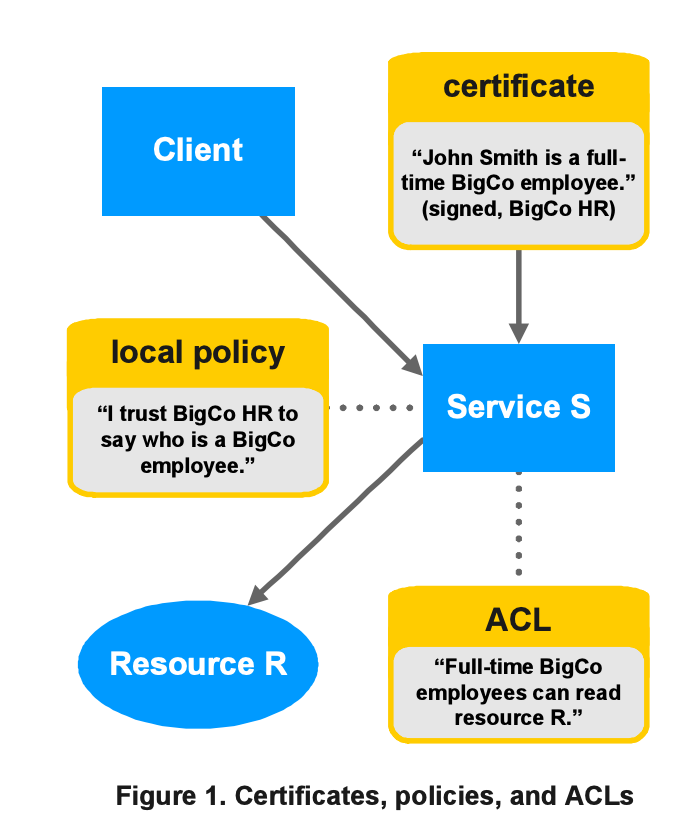

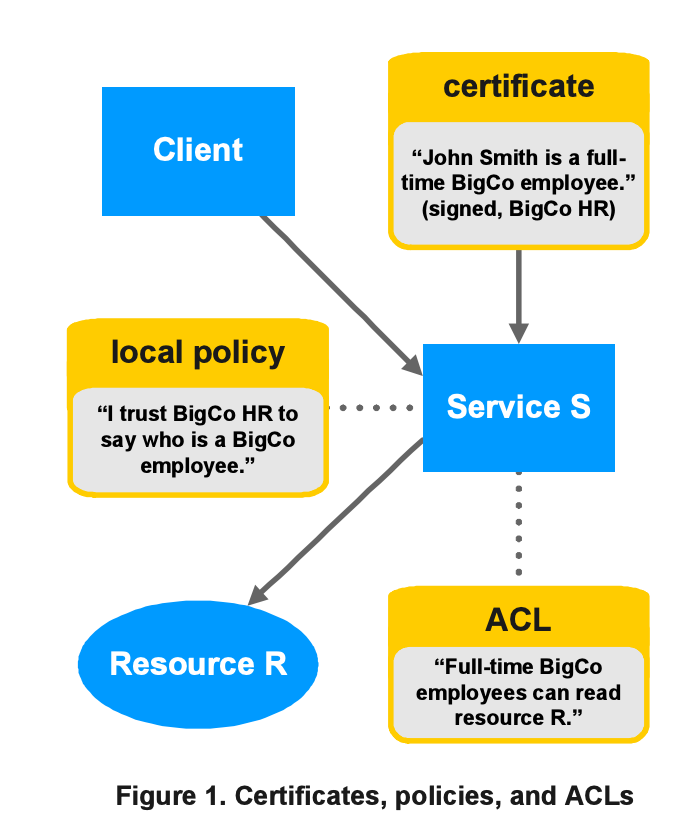

John DeTreville, a computer researcher working at Microsoft, took a note of Prolog's qualities. John noted that Datalog, a subset of Prolog, was a good candidate for a policy language. Policies in Datalog could be merged, cached and queried. In 2002, he proposed a design of a logic-based security language, Binder [9].

John was one of the first researchers to explore the problems of sharing, trust and delegation between different teams and organizations. Binder's design encodes client's information as statements in X.509 Web certificates:

Binder, if ever built for production, would have been a brilliant access control system. Thanks to its use of Datalog, servers could have introspected and queried security rules and statements. One program could have validated and modified the logic behind the decisions made by another program. Client's identity would have been encoded in X.509 certificates, and third parties could have validated and interpreted the data. Binder hasn't been built though, and some of its lessons are still waiting to be rediscovered.

Teleport cybersecurity blog posts and tech news

Every other week we'll send a newsletter with the latest cybersecurity news and Teleport updates.

Access Control System Benchmarks

So where does our search bring us in the end? We haven't found a perfect working system. Learning from the lessons of the past, we now can come up with key properties of a solid access control system.

Bell and La Padula found that access control rules should be able to define, enforce and prove security invariants. For example, non-trusted users should not be able to lower security clearance of a document. Let's call it a security invariant rule.

John DeTreville discovered that users could introspect the logic of the rules. "Tell me what users have access to these servers as root? What rule has allowed Alice to access the system at 3AM yesterday?" We can call it transparency and identity property.

The system should not be overly rigid, or like Bell and La Padula found, you'd have to introduce exceptions to the rules on day two. Therefore, a system should have a flow to elevate privileges. Let's call it a privilege escalation property.

And finally, access control should recognize the distributed nature of organizations and services, and encode the identity that could be independently verified. We can establish it as an identity property.

This might not be a complete set of properties to build such a system, but it might be a minimally required one.

References

- [1] Computer technology planning study

- [2] Looking back at the Bell-La Padula Model

- [3] Secure computer systems: Mathematical foundations.

- [4] Secure computer system: Unified exposition and Multics interpretation

- [5] A Comment on the "Basic Security Theorem"

- [6] Role-Based Access Controls

- [7] ABAC

- [8] Photographic Material and Other Art Work of Herbert E. Striner

- [9] Binder, a Logic Based Security Language

Tags

Teleport Newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the newest Teleport releases by subscribing to our monthly updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter